Curable Blindspot of Culture: How Participatory Arts Ignite Positive Change

Ira and Jewell Williams Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures and African & African American Studies at Harvard University and Director of Cultural Initiative at Harvard

The Curable Blindspot of Culture: How Participatory Arts Ignite Positive Change

How Participatory Arts Ignite Positive Change

Culture is our necessary and renewable resource, the fourth pillar of sustainable development, though we often overlook it. The obstacle, in part, has been the word itself. Culture means two opposite things. One meaning is a heritage of shared beliefs, practices, and places, something to be protected rather than tampered with. This is the sense used by most decision-makers who are trained in the social sciences which privilege patterns over disruptions. The other sense is dynamic and familiar to artists and humanists who disrupt patterns and generate new relationships. One understanding is fixed, making culture either an obstacle to development or a fringe area for decoration and leisure, vulnerable to budget cuts. The other is edgy, experimental, and jealous of personal freedom. This difference in meaning causes a blind spot for both mayors and creatives who see past one another when collaborations are urgently needed to adjust outdated attitudes and behaviours that currently block development toward the SDGs.

Picture above: Copyright: Mannheim Public Library, Copyright Yilmaz Holtz Ersahin and Angelika Senft Rubarth

Today, in a post-pandemic world, we have an extraordinary opportunity to bring these visions together into bifocal projects. Shared beliefs and practices need to be refreshed and updated, as effective leaders know. The vast but under-acknowledged bank of evidence is witness to creativity’s power and potential. This includes a literature review by the WHO of 3,000 studies and an evidence base created by the EU and literally 100s of studies in specific cities. On the other hand, artistic interventions need to take stock of their practical effects, beyond personal satisfaction. Otherwise, we waste the creative resources that make us human. Collaborations will make us better citizens who can re-set our societies after the Covid 19 pandemic exposed habitual exclusions such as life and death inequities. Policies of inclusion in post-pandemic cities can count on participatory arts to foster collective belonging. Arts literacy projects will assimilate immigrants; and immigrant arts will enrich the local offer. (See www.pre-texts.org) The gains will be better security, physical and mental health, economic equity, and care in both senses of loving and taking responsibility for society. In sum, the power of arts as inclusion can energise cities across all dimensions.

The reason is clear. When the general population is engaged in collective and creative activities, they build human and social capital, new personal skills, and admiration for fellow citizens. Collaborations as well as supportive investments will harness the power of participatory arts, which is not the same as entertainment. Entertainment can be enjoyed passively, without engaging the energy of dynamic youth. Youth will build or ravage our cities; they actively participate in civic life or they reject it. And rejection can lead to violence, which simmers during lockdowns and has already exploded in many parts of the world. Our opportunity and obligation is to redirect youthful energy—we cannot extinguish it. Policing and punishment alone have not worked well, nor has single-minded investment in infrastructure. A few examples among many highlight the potential.

1. In 1995 newly elected Mayor Antanas Mockus of Bogota, Colombia faced a city mired in despair, violence and corruption. “Time to bring out the clowns,” counselled his Secretary of Culture. “Good idea,” responded the playful mayor. Twenty pantomime artists replaced twenty corrupt traffic police to shame irresponsible pedestrians and drivers. The shared laughter broke an apparently solid pattern of lawlessness. In the first year, there were 51% fewer traffic deaths. Many participatory arts initiatives followed, along with tax reform, transparency and infrastructural development. But art was the icebreaker. Within two administrations, homicides were reduced by almost 70%; tax revenues increased by 300%. This was “cultural acupuncture,” an approach developed from Jaime Lerner’s “urban acupuncture” for Curitiba, Brazil. Mockus added participatory art-making and accomplished astounding results.

2. Edi Rama became World Mayor of the Year in 2004, mostly for painting the grey city of Tirana in bright colours. It did not solve all entrenched problems, but art did act as a catalyst to rediscover a pride of place and greater respect among citizens. An artist himself, Rama saw colour as more than decoration. It is a structural element to revive the civic spirit. “Beauty was acting like our guardsman… where municipal police, or the state itself, were missing.” This was his winning message in a campaign to become Prime Minister of Albania. Over the last few years, Tirana has made astonishing progress in its urban development, creating an urban forest belt of 2 million trees around the city core where children can plant a tree on their birthday. In 56 months, the city created 56 playgrounds in dilapidated parts of the city that act as gathering places and social connection points for all ages.

3. Broad-based music education has long proved to be a problem-solver, ever since El Sistema was established in Caracas over 50 years ago. By now, almost five million young people in Venezuela have benefitted from classical music training. It won’t make them all professional musicians, but it does teach discipline, focus,

collaboration, and dedication to beauty. Music-making, crucially, keeps vulnerable youth off dangerous streets. Many international projects have imitated this program with notable success.

4. This year Peter Kurz of Mannheim was awarded the World Mayor International Award. Much of his long-term work has involved using the arts to foster intercultural understanding and to regenerate troubled neighbourhoods such as Jungbusch. In Mannheim immigrants make up half of the population and former industries are giving way to new business models focused often on the creative economy. Sceptics about arts interventions sometimes object that they are not inspired, like Mockus, or trained as a painter, like Rama, or an engineer, like Lerner. Yet, Mayor Kurz is not himself an artist. Instead, his talent is to listen and to take small, cost-effective risks on art. One was his support for the School for Oriental Music, a unique initiative that a Turkish musician initiated to gather disaffected youth for rigorous time-consuming and community-building music lessons. This is one of many orchestrated ‘cultural acupuncture’ initiatives through which Mannheim addresses security and education by stimulating creative activities that foster diversity and belonging.

As part of a leader‘s toolbox, participatory arts can play a significant role in addressing the global challenges of SDGs. “Had I understood the power of arts to change behaviour and to drive prosperity, I would have made very different decisions as Minister of Development.” (José Molinas of Paraguay, formerly of The World Bank.) His change of perspective inspires a new “Certificate in Arts and Policy” for city governments in order to engage arts toward achieving a city’s goals, and to articulate particular goals with all the others. Each depends on the articulation: e.g. public health depends on education, transportation, violence prevention, etc. Education depends on public health, transportation, violence prevention, etc. The hybrid virtual and in-person sessions presents existing “Cases for Culture” and then customises co-constructions of new projects for the city’s challenges and resources. The Certificate complements the social science background of most leaders with humanistic thinking that recognises the arts as dynamic vehicles for developing human and social capital. (See https://renaissancenow-cai.org/wp/arts-and-policy/)

In a brief span of time, the Certificate in Arts and Policy consolidates deep European roots of democracy and development. Its people-centred approach can close the short circuit between high investments and low results, through cost-effective investments in art. Why does this work? A short answer is that the arts can include everyone. This means recognising art as the process of making, rather than products. Here participation and inclusion go together. This connection between participation and inclusion structures UNESCO’s broad-based program in arts education and entrepreneurship, “Towards 2030: Creativity Matters for Sustainable Development.”

Who is an artist and who an interpreter? Potentially all of us, to follow Friedrich Schiller who wrote Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man in 1794. That was during the Terror of the French Revolution. Its shock value at the time was perhaps greater than our current pandemic and social upheavals. Slyly, he asks whether art may be an untimely topic for violent times. His affirmative answer is bold and compelling: Without art nothing changes. Humanity spirals into more violence, death, and despair.

Art is the name of development itself. It rejects inherited paradigms and it dares to experiment with new arrangements. If social science understands culture as a system of shared beliefs and practices, as Raymond Williams observed in Keywords, artists and humanists understand culture differently. It is confrontation with paradigms.

Schiller’s passionate call to action is to outsmart violence by breaking from habit and using frustration as a fuel to make something new, a surprise move, an unexpected creation that gives the maker a sense of autonomy and that stops the enemy in his tracks. This is trial and error—the way science works. And Schiller counts on our natural faculty to be creative. We have a drive to play, a Spieltrieb is his newly minted word. When we recognise the human condition as creative—which is evident precisely in under-resourced areas where people recycle and make-do—art is understood as a vital activity in which we all participate. Framing creativity as everyday resourcefulness to alter materials and relationships acknowledges the dignity of all people. Dignity follows from making because the artist is not a victim. Artists know that they have options and that they make decisions, even inside difficult constraints. This sense of autonomy and freedom within constraints is basic to citizenship. People feel proud of their creations and they respect beautiful things that others make. “Beauty was acting like a guardsman,” Mayor Edi Rama knew, “where municipal police, or the state itself, were missing.” He invited citizens to deliberate about colour and design to paint bright colours over old grey buildings. Even beautiful patrimonies of art, architecture, and monuments are there to be used. They offer historical continuity with precious urban spaces that link the past with the future. During the present COVID-19 restrictions on movement, digital programming has bought these sites of cultural heritage to an expanded virtual public.

Making autonomous choices through artistic practice channels the frustrations that many young people feel in our overcrowded and under-resourced neighbourhoods. Through art they can provoke and criticise in non-violent ways. “Symbolic violence” is another name for art and a pathway around the real thing.

Creativity is what distinguishes our species from other animals. Many are intelligent, but only human beings are imaginative beyond strategic thinking. Knowing this obliges us to create new things and new social arrangements. This is the theme that Josef Beuys made popular to repair the world after WWII when he established Documenta, the most important international art event, celebrated every five years in Kassel, Germany. As we speak, a stage of Documenta is being set for collaborations, because unlike previous editions, the 2022 event will promote community-oriented collectives. Artists have understood their urgent obligation to renovate creative practices and to adopt social and climate challenges. Today, artists, engineers, and educators offer initiatives to leaders who can recognise good bets and take necessary risks. This is the spirit of the early modern Renaissance. When the Medici bet on young Brunelleschi to build a monumental Cathedral dome, other investors scoffed at the folly. But the bet paid off, and the winners included the Medici, the artist and the entire city of Florence. In contemporary Italy, opera trucks are familiar interventions in immigrant neighbourhoods. Examples like these can help to ignite a new Renaissance Now with collaborations that take account of people’s creativity and that generate civic pleasure to keeps us engaged with each other as we face global challenges.

Doris Sommer

Doris Sommer is Ira and Jewell Williams Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures and of African and African American Studies at Harvard University. She directs the Cultural Agents Initiative at Harvard, and the Cultural Agents NGO dedicated to reviving the civic mission of the Humanities. Her projects include “Pre-Texts,” an arts-based training in literacy and citizenship, and Renaissance Now, a forum for rethinking culture in development. Her books include Foundational Fictions: The National Romances of Latin America (1991) about novels that helped to consolidate new republics; Proceed with Caution when Engaged by Minority Literature (1999) on a rhetoric of particularism; Bilingual Aesthetics: A New Sentimental Education (2004); and The Work of Art in the World: Civic Agency and Public Humanities (2014).Sommer’s work span’s Harvard’s Humanitarian & Cultural Initiative at the Mahindra Centre, the Executive Committee of the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, the American Studies Program, the Committee on Ethnicity, Migration, Rights (EMR); the Centre for Public Service and Engaged Scholarship & Global Health and Health Policy, South Asia Institute, and the Modern Language Association’s Working Group on K–16 Alliances. Recently, she prepared the Brief on Culture for the Summit of the Global Parliament of Mayors. Picture © Harvard Gazette

Renaissance 3.0

Artistic-scientific Director and CEO of ZKM Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe and Director of Peter Weibel Research Institute for Digital Cultures at University of Applied Arts, Vienna

Renaissance 3.0

A scenario for art in the 21st century

The turn of the 21st century has been marked by a series of crises on a global scale. Through the infosphere, that electromagnetic envelope that surrounds Planet Earth and which we have been using for communication since the mid-19th century through radio technology, from telephones to satellites, a global society emerged in the course of the 20th century. News that used to take months from source to receiver—of earthquakes to stock market fluctuations—is now distributed almost simultaneously across the globe. The mass mobility of people and goods has additionally created a condensed global society. As a result, crises are not limited to local topographies, but spread globally. From the climate crisis to the migration crisis, from the financial crisis to the COVID-19 crisis, we are witnessing ever more profoundly shattering consequences. Principles of our civilisation built on the successes of humanism and the Enlightenment—for example, the universalism of human rights, equality of race, gender and age before the law, autonomy of the individual, freedom of the press and arts, democracy—are increasingly being challenged. Due to the climate crisis, the overall habitability of Planet Earth by humans—and thus humanity’s ability to survive—is being called into doubt. Mass migrations in the coming decades could therefore radically change the face of the Earth and the social systems that have

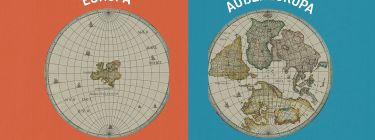

Picture above: Peter Weibel, Copyright: ZKM | Zentrum für Kunst und Medien Karlsruhe, photo by Christof Hierholzer

prevailed up to now. Therefore, it is necessary to propose a navigation system that prevents the failure of the mission of humanity on the good ship Earth. One of the possible scenarios for the future seems to us to be the revival of one of the greatest moments in human history, namely the Renaissance.

Most people think of the Italian Renaissance (15th, 16th and early 17th centuries) when they hear the term Renaissance, which stands for an era that surpassed anything that had gone before in terms of freedom, progress and discovery. However, it is important to note that there was an Arab Renaissance before the Italian Renaissance, from 800 to 1200, which has only come into focus in recent years.1

Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance stands for a cultural revolution that ushered in a new attitude to the world and to humanity that was decisive in the history of the Western world. For many people, the Renaissance is regarded as a time of new beginnings, in which art and science flourished as never before and as never since. An example of this could be the painting La scuola di Atene (The School of Athens) by the painter Raphael, which he realised in the Stanza della Segnatura of the Vatican from 1510 to 1511. The title of this painting illustrates a central important aspect of the Renaissance, namely the rebirth of antiquity. Similarly, the rediscovery of Lucretius‘ ancient text De rerum naturae (On the Nature of Things) influenced artists like Botticelli, but also scientists like Bruno Giordano and Galileo Galilei. The last existing copy was discovered in a German monastery in 1417. Erwin Panofsky pointed out in his seminal work Idea: A Concept in Art Theory (1924) that the terms idea and type originated in the philosophical vocabulary of the Greeks, from which developed the cult of the ideal that prevailed in Europe until the days of Romanticism. That is why German masters such as Albrecht Dürer, and the three Nuremberg masters who worked with perspective representation——Lorenz Stöer, Wenzel Jamnitzer and Johannes Lencker—should also be considered.Decisive for the Renaissance, however, is Leonardo da Vinci’s quote, „Se la pittura è ’scienza o no,” with which he opens his famous manuscript Trattato della pittura (written circa 1490, published 1651). The claim was quite clear: „Painting is a science.” Renaissance, then, is the scientification of art. That is a central aspect of the Renaissance.

Up until the Renaissance, artists were considered craftsmen, belonging to artes mecanicae. In the Renaissance, they increasingly saw themselves as representatives of the artes liberales, i.e. as scientists and scholars. Renaissance artists repeatedly portrayed themselves as scholars, for example by featuring compasses, mirrors and small globes in their self-portraits as well as depicting their tools of the trade: canvases, brushes, perspective devices, and so on. Federico Zuccaro staged himself in his self-portrait as a reader of a book. These artists were concerned with optics and rays of vision and the theory of proportions. Piero della Francesca was, as it were, a calendar mathematician. He was interested in the doctrine of polyhedra.

A second central aspect of the Renaissance was the discovery of the individual. Whether in art, science, economics or politics, it was individuals who devoted themselves to exploring new horizons, new spaces at their own risk, be it the exploration of the seas by Columbus and Magellan or of celestial bodies by Galileo. The artist, the navigator, the explorer discovered new worlds, often against prevailing ideologies and doctrines. The Renaissance was thus the epoch of the triumph of individuality and this triumphant march has continued to this day. From the architecture of a Palladio to Titian, from Leonardo da Vinci to Giulio Romano, from Benvenuto Cellini to Michelangelo, we observe the the discovery of the individual.

Art as science and the expression of the individual’s abilities are thus the two most important aspects of the Renaissance for the future of art.

Arab Renaissance

But the Italian Renaissance was not the first scientification of art. The Arabic Islamic Renaissance occurred between 800 and 1200. The Banū Mūsā brothers created programmable musical automata around 850. Ibn al-Razzuz Al-Jazari wrote the book Compendium on the Theory and Practice of the Mechanical Arts around 1200. From Baghdad to Andalusia, Arab artists and scholars, such as Ibn Khalaf al-Murādī and Abū Ḥātim al-Muẓaffar al-Isfazārī, rediscovered and advanced Greek and Byzantine traditions. For example, the term algorithm comes from a Latinisation of the name of the Arab scholar Abu Jafar Muhammad ibn Musa al-Chwārizmī. As Hans Belting has documented in Florence and Baghdad, Abū ‚Alī Ibn al-Haiṯam (965-1040, known in the West as Alhazen) wrote Kitāb al-Manāẓir. His work was translated into Latin in the 12th century and contains fundamental studies on the propagation and refraction of light. The reception of Ibn al-Haiṯam’s theory of light and vision triggered one of the most exciting chapters in the history of Western art. Alhazen can be considered the inventor of the camera obscura and the forerunner of the invention of perspective. Perspectiva was the Latin title of his Arabic work on optics which was later replaced by the Greek term Optics and then again by the Latin Opticae Thesaurus (1572).

Renaissance 3.0

In this respect, the Arab Renaissance was the first, the Italian the second, and now in the 21st century there are convincing signs that we are experiencing a third Renaissance. In contrast to the two, relatively localised Arab and Italian Renaissances, the latest manifestation is global. Artists from China to Chile form a new generation of art-based research and research-based art. New works of art and scientific theories are emerging that do not only refer to the historical achievements of the preceding renaissances. Clearly, there are continuations of lines of tradition. For example, façade decorations by Falconetto in Verona foreshadow projection mapping on public buildings. Likewise, Paolo Veronese’s frescoes can be seen as precursors to immersive environments. In the future, new scientific disciplines, especially expanded forms of the life sciences, will determine our lives. The new society will therefore not only be about automata and robots; there will also be a shift from the mechanical and machine-based renaissances: that is, from hardware, to the new renaissance of software, programming, codes.

In this respect, genetics, molecular biology, all forms of the new life sciences, artificial intelligence, quantum optics, climate research, health care, the infosphere, the data society, questions of cyborg feminism (see Donna Haraway and Joanna Zylinska) will be central.

In the 21st century, there is a new basis for the convergence of the arts and sciences. Artists and scientists share a common „pool of tools“. Tools that dentists use, for example, small cameras that illuminate the oral cavity, are also used by artists. The same computers and screens are used by artists and scientists, as are algorithms and data networks. Mathematical equations slide over into genetic entities, both for physicists and artists, and geometric entities and fluid objects transform into data, into data curves, both in science and in art.

As long as art remained within the horizon of visible things that our natural organ, the eye, captures, it was difficult to build a bridge to science which, since the 17th century, has captured the world with instruments and apparatus, from telescopes to microscopes. With such apparatus, science opened the door to the previously inaccessible res invisibiles. As long as art refused to use such apparatus, it was fundamentally different from science. Art ended at the limits of natural perception. Science begins where natural perception ends, that is, beyond natural perception. With the rise of media since photography (circa 1840), media art also uses apparatuses and algorithms like science. This is the new basis of the convergence of science and art for a new renaissance.

The art of the 21st century will be dominated by this Renaissance 3.0 and will thus face the many challenges of humanity. One of these challenges is that the function of art and science to give meaning to the rerum naturae (Lucretius)—to the things of the world and nature, and to human beings—is being reinstated at this historical moment even as the function of science is being doubted. Hegel famously claimed that after religion and art, it is philosophy that recognises the absolute, that is, that gives us meaning and knowledge. We plead for defending the function of art and science against the current sceptics, as is necessary today more than ever as we experience climate and pandemic crises. The Renaissance 3.0 project will open the general public up to an unprecedented horizon of innovative works of art and, as the Italian Renaissance achieved, a new attitude towards the world and the future of symbiotic life of all living beings on Planet Earth.

References

1 Siegfried Zielinski, Peter Weibel, Allah’s Automata. Artifacts of the Arab-Islamic Renaissance (800-1200). Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz 2015

Peter Weibel

Peter Weibel is the artistic-scientific director and CEO of the ZKM Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe and the director of the Peter Weibel Research Institute for Digital Cultures at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna. He is considered a central figure of European media art on account of his various activities as an artist, theoretician, and curator. He publishes widely on the intersecting fields of art and science. His career took him from studying literature, medicine, logic, philosophy, and film in Paris and Vienna to working as an artist and lecturer and then to heading the digital arts laboratory at the Media Department of New York University in Buffalo from 1984 to 1989. He later became the founding director of the Institute of New Media at the Städelschule in Frankfurt from 1989 to 1994 and professor of media theory at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna from 1984 to 2011. He was the artistic director of the Ars Electronica festival in Linz from 1986 to 1995, the Seville Biennial (BIACS3) in 2008, and the Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art in 2011. He commissioned the Austrian pavilions for the Venice Biennale from 1993 to 1999 and was the chief curator of the Neue Galerie in Graz from 1993 to 2011. Picture © ZKM | Zentrum für Kunst und Medien Karlsruhe, photo by Christof Hierholzer

Renaissance by mistake

Prof. Pier Luigi Sacco, PhD, Professor of Cultural Economics at IULM University, Milan

Renaissance by mistake

Spirit, are you there?

Leonardo da Vinci is probably the most acclaimed creative mind of all time and the epitome of the Renaissance man. His knowledge, talents, vision, and imagination spanned several disciplines that sadly now constitute different cultures: Science and Art. We admire Leonardo so much not only for what he did, but also and maybe even more for what he anticipated: in his notebooks, he figured out ideas and possibilities that would only become a reality several centuries later. And yet, if we think of it, most of what we admire Leonardo for did not work. His tank or his submarine, to cite a few famous examples, are brilliant intuitions, but nothing more. Even an artistic masterpiece like The last supper is in critical condition because Leonardo experimented with a new painting technique of his own invention, a tempera grassa, that would fail to stick properly to the humid wall. A detractor of his time would not have been in a difficult position in depicting Leonardo as a fraud by selectively picking a collection of such incidents. But his experimental, risk-taking attitude was a constant feature of his creative method. This raises an interesting question: Do we admire Leonardo because of his mistakes or despite his mistakes?

Mistakes and the Renaissance Men: then and now

We could be tempted to say, Neither one nor the other. We do not admire Leonardo because he did something wrong, but because he was visionary enough to imagine possibilities that were much beyond the technological standards of the time, and inevitably he could not get them right given the current state of knowledge. At the same time, blaming him for not getting them right would be totally unfair in view of the fact that actually working submarines or tanks would in the first place require engines that were inconceivable at the time of Leonardo. But can we really separate in any way Leonardo’s prodigious ingenuity from the ‘mistakes’ it produced? After all, most of Leonardo’s imagination of possibility comes from a careful and most insightful observation of nature: his machines are distillations of design principles found in animal bodies, and of reflections on the action and properties of natural forces. And like Leonardo’s, such evolved principles have in turn been built by nature on the basis of

constant trial and error, of endless refinement of mistakes: After all, what else are the copying glitches that cause genetic mutations?

In the constant lip service to Renaissance that is so much characteristic of our times—the idea of Renaissance has probably never been so popular as it is nowadays so that practically every day somebody calls for a ‘new Renaissance’ of some kind—we seem to have learnt this lesson in its iconic translation in the biographies and visions of those who are generally reputed and celebrated as the contemporary equivalents of the Renaissance man: self-made digital economy tycoons like Steve Jobs, Sergey Brin and Larry Page, or Elon Musk, all of whom have built their fortunes through a relentless toggling between moments of sheer defeat and utter triumph, with the former providing the lessons that paved the way to the latter. Samuel Beckett’s “Fail again. Fail better” quote has become the most famous inspirational quote of Silicon Valley culture (and it is difficult not to feel the irony of all this). We have understood how to make sense of mistakes and profit from them, after all.

A culture of making mistakes is not a mistake in culture

But is this really the case? It is true that, retrospectively, mistakes can be good and are seen under a different light once one recognises how they prepared the condition for later success. But when mistakes are made, it is much more difficult to take them cheerfully, especially when one is moved by an enthusiasm and sense of possibility that clash with sudden, sometimes brutal denial. Being mistaken may sometimes sound like being treated unfairly in terms of lack of responsiveness to something that deserved more attention and consideration, and it really hurts. What is or is not a mistake does not depend only on objective conditions but may also reflect social circumstances. A good idea can become a mistake when it is proposed ahead of the time and is basically not understood by others—but is it then a fault to see things long before others do, as

Leonardo did? Or can it become a mistake because it conflicts so much with the incumbent vested interests that it becomes a threat that needs to be eradicated? To change a mistakenly good idea into a success, sometimes you do not need to change the idea, but the environment. And this is, ultimately, what the Renaissance largely did (to be fair, not in opposition to a supposed, previous Dark Age as it has been long contended, but through a seamless development of

long-baked previous ideas). It created a social milieu that was welcoming and favourable enough for creative minds that would have been out of place and out of context in most other societies, and whose ideas would have been refused as mistakes in different circumstances—as it would become clear a bit later in the gloomy times of the Counterreformation.

Todays Paradoxes trapping a Next Renaissance

So, the question becomes: Are we prepared to take the responsibility of what it means to invoke a new Renaissance? Are we prepared to set the context for good ideas not to sour into bad mistakes? The same society that celebrates Renaissance genius is keen to embrace an educational model in which only STEM disciplines matter (“Leonardo, stop wasting your time painting and try to make that damn plane fly!”). This same society seems to be willing to cut funds for basic research to reallocate them towards ‘useful’ applied research (“Leonardo, stop wasting your time with that tank thing and come up with a practical idea!”). It is easy to see how our current choices are turning into ‘mistakes’ the same attitudes that we retrospectively celebrate. Paradoxically, what attracts us to the idea of Renaissance genius is that we leave our trust to the creative vision as a way of maintaining our own need for assurance and risk-aversion (‘the genius will do it right, even if I do not understand how and why’). However, what makes it feasible is exactly the contrary: Responsibly embracing collective risk-taking is the only viable context for successful creative ideas.

So, what does a ‘new Renaissance’ mean today, concretely? It means being able to create a social attitude of openness toward the weird and the unfamiliar. Weird, unfamiliar things can be very irritating, and we are generally not very good at managing irritation. Truly new ideas are often refused not because they appear too complex, but because they appear too stupid—largely because we are not able to appreciate their real depth and complexity. Weird, unfamiliar things call for cognitive and emotional effort. But we live in a world in which we are much too keen to simplify things to people. And perhaps not accidentally we witness an unprecedented flourishing of spurious or entirely fabricated knowledge (‘conspiracy thinking’) whose only real appeal lies in its nodding to our need to understand the world through ideas and categories we are already familiar with and require no real learning or cognitive effort. We are often suspicious of anything that challenges our prejudices and intuitions.

Recovering the Renaissance spirit

The road to a ‘new Renaissance’ is long and tortuous, and it passes through an unprecedented mass flourishing. To turn mistakes into good ideas we need societies that are ready to venture into the unfamiliar with grit and curiosity, and that have the patience to absorb delusions and the generosity to overcome partisan thinking. But this sounds exactly like the opposite route to the one pursued by the business models of many of those digital giants who, ironically, we celebrate as the modern incarnations of the Renaissance spirit. These are businesses that profit from the increasing polarisation of the public opinion and from the formation of echo chambers that commodify people’s prejudices.

Recovering the Renaissance spirit is about turning the tide. Digital culture can become the platform for a new Renaissance if it does what the Renaissance once did: creating a social platform for an unprecedented form of collective intelligence. And Europe can play an important role in this process exactly because it does not have such an incumbent interest in the extraction of value from the status quo as is the case for the Silicon Valley giants. Europe can pursue different possibilities because it has much less to lose—and much more to gain. But to do so, we need to recover the true social dimension of the Renaissance whose locus is not the studio of the solitary genius, but the square: the centre of community life, the

theatre of exchanges and encounters. The Renaissance square is inclusive, it is a public space that everybody can inhabit as a peer, and it is pertinent that the square as the centre of human-scale community life is a typically European urban phenomenon.What is the public space that we may inhabit in our ‘new Renaissance’, and where is it? What are the conditions for access, and who controls them? What ensures that it is diverse and inclusive enough to welcome mistakes and turn them into good ideas? These are the questions that we need to credibly answer if we want to take a new Renaissance seriously. And not to do it would be a mistake—one that would be difficult to turn into a good idea under all circumstances.

Pier Luigi Sacco

Pier Luigi Sacco, PhD, is Senior Advisor to the OECD Center for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions, and Cities, Associate Researcher at CNR-ISPC, Naples, and Professor of Economic Policy, University of Chieti-Pescara. He is also Senior Researcher at the metaLAB (at) Harvard. He has been Visiting Professor and Visiting Scholar at Harvard University, Faculty Associate at the Berkman-Klein Center for Internet and Society, Harvard University, and Special Adviser of the EU Commissioner to Education, Culture, Youth and Sport. He is a member of the scientific board of Europeana Foundation, Den Haag, of the Advisory Council on Scientific Innovation of the Czech Republic, Prague, of the EQ-Arts Foundation, Amsterdam, and of the Advisory Council of Creative Georgia, Tbilisi. He regularly gives courses and invited lectures in major universities worldwide, published about 200 papers on international peer-reviewed journal and edited books with major international publishers. He works and consults internationally in the fields of culture-led local development and is often invited as keynote speaker in major cultural policy conferences worldwide.

physical-virtual-virtual-virtual-physical-physical-virtual-physical-physical-virtual-physical-virtual-virtual-physical-virtual-virtual

Alejandra Panighi, Strategic Consutant at Mediapro, Madrid

physical-virtual-virtual-virtual-physical-physical-virtual-physical-physical-virtual-physical-virtual-virtual-physical-virtual-virtual

In which metaverse do we want to live?

The Metaverse—A ubiquitous, synchronised universe where presence and sense of presence become indistinguishable.

For those of us who were born in the 20th century, the word „metaverse“ came to be associated with science fiction books and films of the 1990s which depict a dystopian future dominated by technology. In most of them, humanity is dominated by mega corporations, totalitarian governments or dehumanised scientists who use simulated worlds and robotic environments to subject people to situations of oppression, domination and injustice.

But for those who grew up with the online world as an integrated space within the physical world, the metaverse is simply a collection of all the virtual universes that coexist in the cloud and are necessarily shared, interactive, immersive and collaborative.

The metaverse is, for this generation, understood as an environment where the digital assets become an extension of the physical assets—precisely a moment when the blurring of this distinction simply happens.

It began perhaps with the mobile internet, and just accelerated with advances in the use of AR (Augmented Reality), VR (Virtual Reality) and AI (artificial intelligence) until becoming an increasingly present and ubiquitous mixed reality.

Creative industries, particularly video games, went deep into this concept of real-digital and digital-real, making immersive experiences a language of a generation who learned to live and enjoy these environments in which the physical person and its own digital extension coexist and converge.

It is now the same generation that expects to integrate into this metaverse all the other aspects of their lives: sports, social activities, academic life, travel, work and global economy.

For several years, the narrative about this metaverse, as something real outside of films and books, was captive of those who worked to revolutionise the actual rules of Internet, developing the virtual economy from different but close perspectives. It was almost a cryptic universe, accessible to those who could quickly understand the token economy and its fungible and non-fungible tokens and the rules of permissions and permissionless environments—among many other concepts—in which „old“ inventions like Napster would have been unstoppable.

That is until 2021, when Facebook divested itself of its original brand and became Meta by announcing multi-million-dollar investments in augmented and virtual reality, robotics, high-tech VR glasses and sophisticated software applications to make the old Facebook social media network an environment for communication, fun and work in the metaverse.

Other giants of the internet 2.0 era such as Google, Microsoft or Apple also unveiled their plans to develop virtual environments with huge investments. This sudden trust in the virtual economy became a fillip for hundreds of start-ups who could suddenly access a flood of money in projects that few months ago previously have been considered extremely risky. How quickly and how much further it might go is yet to be seen, but lots of ethical questions are raised when we think about a near future where both worlds, the Physical and the Virtual, get together and shape our lives in a constant physical-virtual-virtual-virtual-physical-physical-virtual-physical-physical-virtual-physical-virtual-virtual-physical-virtual-virtual dialectic.

There are at least two main visions of how this Metaverse should be…

One is inherited from the current model of society, led by closed platforms and Big Tech that are not necessarily the bad boys of so many dystopian novels. But there are indeed few and dominant players of the digital economy of the 21st century. They claim the central role such huge machines should be allowed to have, to make this Metaverse happen in an ordered and controlled way, far from actual wilderness of the internet sphere that includes the worst we can see from ourselves in the deep and dark web.

Another vision, in stark contrast, talks about an Open Metaverse created with open technology and open protocols that allow increasingly decentralised and accessible environments for almost anyone. This is the vision of those creators of—and believers in—Web 3.0, which has been evolving for at least 10 years. They advocate for an Open Metaverse based on principles of digital sovereignty and easy access to data and protocols for people to achieve a new world economic order, an order perhaps better, perhaps fairer, perhaps more promising for those who now lie at the bottom of the actual world’s economy.

A third vision, probably the most plausible one, is a coexistence of both centralised and decentralised visions, convergent and divergent environments in which any kind of ordering or regulation will be complex but might prove necessary.

In any case, during the next few years we will experience a true ethical, moral, ideological and economic revolution that is somehow reminiscent of the profound change in society that took place during the Renaissance.

In these times, we will see the scaling of this virtual-based economy, environmental challenges, not only those arising from the digital economy but also those inherited from the current economy, new jobs and the transition between the old jobs and the new ones, and so many other challenges and so many inconsistencies in the meantime.

We’ll need to go through a deep revision of the grounds of Internet, the deepest since it was born:

– the whole process of capture and control of data

– the cost of electricity or other renewable power sources

– accessibility to digital resources

– the conversion from actual sleeping goods in Cloud wallets to the commercial retail system

– the backend of the internet (hardware and software)

– the actual network and nation-based technical infrastructure

– operating systems.

… And so many other concepts raising from the revision of these basic ones.

But also, rethinking what identity means, what belonging means. What is a community? What is fandom? Or random? The possibility of

multiple identities for each person—physical and digital—and a possible total sovereignty for each opens up an unexplored universe.

The sovereignty of identity in the physical world, in the virtual world and in what emerges from the combination of both universes for future generations may completely change social relations in the decades to come.

Somehow, once again, as in Europe’s First Renaissance, the New Renaissance will be all about the convergence of Culture, Economy and Technology.

Alejandra Panighi

Born in Argentina, she started her career in TV in America as producer and journalist, but she was always attracted by all ways of storytelling in almost any written or visual formats too.So it was not a surprise when, in early 90’s, she joined the team that launched Yahoo and AOL portals in the American continent, when they were still a web directory of content curated by people. She experimented with live shows and live interviews with musicians, interacting also with those the few users who could access dial up connections for several minutes. Living in Europe for the last 20 years, she’s been focused in innovation of the film, series, live sport and eSports industries, looking for different business models and new ways of reaching audiences. She embraces technology as a driver for innovation and follows consumer’s behaviour with passion. From VR-XR to immersive experiences, from data management to AI and moving now in the arena of virtual economy her wide expertise on the evolution of the Audiovisual industry is an asset. Focused in EU policy for the last decade, she lives in Brussels and works as a strategic consultant for Mediapro Group, dealing directly with the Board of Directors.

Picture © Pepe Encinas (Barcelona, Spain)

Digital transformation as a second renaissance?

Prof. Dr. Dr. h. c. Julian Nida-Rümelin, Staatsminister a.D., Director of Bavarian Institute for Digital Transformation and Vice-Chair of German Ethics Council, Munich

Digital transformation as a second renaissance?

Towards digital humanism

The European Renaissance began first in Italy after a period of exhaustion by plagues, misery and wars. In the mid-14th century, the plague had plunged Europe into one of the worst catastrophes of mankind, an incurable disease that brought great pain to those afflicted and usually a quick death. Even before the plague, a long-lasting famine had taken hold, for which climate change in the form of significantly falling temperatures probably played a decisive role. The structures of social order eroded and everyday life became brutalised. The population declined markedly, with the paradoxical effect of a valorisation of human labour and an increase in productivity brought about by new technologies. The European Renaissance was preceded by a creeping decline in the authority of clerical and princely authorities, and was characterised by a return to ancient thought, especially that of the Greek Classical period and the Roman Empire. Aristotle was disposed of—prematurely—because the Thomasian worldview, unlike patristics, was based on his writings and had made them the authoritative source alongside the Holy Scriptures.

The young intellectual Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494), born into high wealth and highly gifted, published his writing De hominis dignitate (Rede über die Würde des Menschen EA: 1496) and ensured that it was discussed throughout Europe by intellectuals and eventually also by ecclesiastical authorities. At the centre was an image of God that endows man with artistic creativity, technical innovation, and scientific research; indeed, one might say that in this writing Pico della Mirandola anticipated the thesis of the analytical philosopher Roderick Chisholm that man, like God, is an unmoved mover (Die menschliche Freiheit und das Selbst (1964), S. 82). Human creative spirit completes the work of God. Humans as rational beings are authors of their own life. They are free and therefore bear responsibility for everything they do. Only Immanuel Kant thought the consequences to the end in his practical philosophy of autonomy.

The Renaissance was an epoch of impressive innovation. And like other innovative periods in human history, it was characterized by the breaking up of schools and conventions, by interdisciplinarity, and by the fluid transition of philosophy, science, technology, and art. Education was no longer the learning of preconceived patterns of thought and practice, but self-education with the goal of life-authorship. Leonardo da Vinci did not know whether to see himself as a scientist, technician or artist. The Renaissance cities became documents of impressive design in the combination of technology, craftsmanship, art and science.Are we on the threshold of an era of comparably far-reaching innovations, shaped by the potential of digital technology? To be able to assess this, we first have to face a sobering fact. The third wave of digitisation has not yet made a significant contribution to either labour-hour or resource

productivity. The platformisation of the economy has reshaped it to some extent and created large tech giants, but it has not stimulated growth, or at least not noticeably. In a ranking by the World Economy Forum a few years ago, Germany landed in first place among the most innovative countries in the world—probably to the surprise of the authors—while at the same time being one of the most digitally backward. Working hour productivity in Germany is almost a third higher than the EU average while almost all European countries are outstripping Germany in terms of digital transformation. The productivity of the German economy is just behind Norway and Switzerland, but well ahead of France, Canada, the U.S. and Japan (which leads the East Asian countries). The productivity boost that digitisation triggered with the introduction of personal computers and the use of the Internet in the 1990s has not been repeated in the third wave. At the same time, however, the world is in dire need of a technologically-driven increase in productivity in the face of resource scarcity, ecological depletion and climate change.

All the inadequate efforts to cut CO2 since the 1990s have been far outweighed in Europe by the additional CO2 emissions of the Chinese economy. Meanwhile, the Chinese economy is polluting the atmosphere with climate gases at a higher rate than the US and Europe combined—even though China’s economic output ranks only third after the US and after the EU. If other current and future boom regions such as India or sub-Saharan Africa follow the development path of China, the climate catastrophe in large parts of the world cannot be stopped. The digital transformation must enable other development paths and use human and natural resources far more sparingly without stifling economic momentum in a development phase where the demographic dividend pays off in the global South.

Inventiveness, interdisciplinarity and creativity—the human ambition to master the existing challenges and not to be driven by apocalyptic fears into helpless protest or resentment-laden apathy—are required. A rapid changeover to climate-neutral and ecologically sustainable economic activity, first and foremost in the highly industrialised countries, the treading of new technological, economic and social development paths in fair cooperation between the world’s regions and the mobilisation of human resources in order to overcome the major challenges facing humanity will only be possible with the massive use of digital technologies.

Not data thriftiness, but protection of personal rights and use of data for humane progress in medicine, natural science and education, in state administrations, small and medium-sized enterprises, the efficient and effective organisation of social cohesion, are indispensable for this. The humanistic ideal of human authorship, self-education and creative power must experience a renaissance under digital auspices.

Responsibility remains solely with human actors. Software systems, highly developed so-called „autonomous“ ones as well as those which are called „artificial intelligence“ (AI), are not actors, not people. Man does not become God, who creates other individuals in his image to use them at will for himself. They are merely technical, albeit highly sophisticated, tools that we should use individually and collectively, legally framed and politically shaped, for the good of humanity. This is the central message of Digital Humanism: machines are not people and people are not machines. The currently fashionable AI animism is unscientific mumbo jumbo, a projection of a familiar type that animates the unsouled and gives satisfaction to the swashbucklers. And man is not a machine, not an algorithm-controlled software system, but a freely responsible actor of his actions. Digital technologies will not relieve him of this responsibility, but neither will they take away his freedom to individually and collectively shape life and its conditions.

The renaissance of digital transformation is based on the empowerment of human authorship, on the development of human creativity, on the targeted, intelligent and measured use of new technologies for human purposes. It aims to humanise the world of work through sustainable production and the establishment of fair practices in the global economy, while the current development path has established monopoly structures in the form of large tech giants, shifted greater parts of economic value creation to platforms and made a successful business model out of the skimming of user data from digital service offerings for marketing purposes. This humanistic form of digital transformation will not be feasible without a state framework in the form of digital infrastructures, without an independent European path of „human centred AI“ and transparent uses while safeguarding informational self-determination rights, without a European legal framework of digital dynamics. But the chances are good that the humanistic form will ultimately prevail over the commercial model of Silicon Valley and the state control model of China and other autocratic and totalitarian states.

Prof. Dr. Dr. h. c. Julian Nida-Rümelin, Staatsminister a. D.

Julian Nida-Rümelin teaches philosophy and political theory at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich.JNR was a member of the first Schröder cabinet as Minister of State for Culture and Media. He is a member of the Academy of Sciences in Berlin and the European Academy of Sciences, director at the Bavarian Institute for Digital Transformation (bidt). In 2016, the Bavarian state government awarded him the medal for special services to Bavaria in a United Europe. In 2019, he received the Bavarian Order of Merit. Since May 2020, he has been a member (as deputy chairman) of the German Ethics Council. In 2016, Humanistische Reflexionen (Humanistic Reflexions) was published by Suhrkamp. In the fall of 2018, he published a monograph on Digitaler Humanismus: Eine Ethik für das Zeitalter der künstlichen Intelligenz (Digital Humanism: An Ethics for the Age of Artificial Intelligence) (Piper Verlag), for which he received the Bruno Kreisky Prize in Austria for the best political book of the year. In spring 2020, edition Körber published Die gefährdete Rationalität der Demokratie (The Endangered Rationality of Democracy) and DeGruyter Eine Theorie praktischer Vernunft (A Theory of Practical Reason). Picture © Diane von Schoen

Renaissance, the world and Europe

Sir Geoff Mulgan, Professor of Collective Intelligence, Public Policy & Social Innovation at University College London and Fellow at The New Institute, Hamburg, and Demos Helsinki

Renaissance, the world and Europe

Beyond the obvious

In the middle of the 20th century Europe was ravaged by world war. But it continued to dominate the world. The empires of Britain and France remained vast. Europe accounted for over a fifth of the world’s population and most of its largest economies.By the middle of the 21st century that will all have changed dramatically. Europe’s share of world population will be closer to a twelfth; its economies will have been overtaken not just by China and India but possibly by others such as Brazil and Nigeria. Its military might will be modest compared to the superpowers.

Moreover, many of the things that might have once seemed uniquely European no longer do. There are many examples of healthy democracies and many examples of the rule of law. Science is more generously funded in countries like South Korea or Israel than most of the EU.

To the extent that people across the world talk about European values, they talk as much about slavery, exploitation and genocide as they do about human rights.

So, any discussion of renaissance has to be tempered by humility. Too much European self-love feels ever less appropriate to the times.

Picture above: Geoff Mulgan, Copyright: NESTA

What Europe has however sustained is a unique mix of features that remain attractive to the rest of the world. We remain good at combining security, prosperity, democracy and ecology. In the developing world people speak of “getting to Denmark” as the typical objective for most of the world’s poorer countries.

And part of that mix is being at ease with creativity, exploration and discovery. That hunger for challenge is not only still missing in many places but is also in retreat—squeezed in Xi’s China, blunted in Erdogan’s Turkey, frozen out in Putin’s Russia, ideologically constrained in Modi’s India.

This makes it all the more important that Europe continues to try to imagine, to fuel creative imagination. To me the heart of this is to imagine not just how the world could get to Denmark, or how to assert our values, but rather to think forward to a plausible and desirable picture of what societies could be like a generation or more from now.

What might a truly zero-waste and zero-carbon society look like? How could democracy evolve to make the most of collective intelligence? How can we live with hugely powerful artificial intelligence in ways that help us thrive? How will we live with far more free time, the result of shrinking working hours and rising life expectancy?

This is the imaginative space that is so badly needed now and at the heart of any plausible renaissance. But at the moment, in Europe as elsewhere, the thinking is weak and constrained.

The universities have largely given up on their role in exploration of the future (something I have written about, with suggested remedies, for the New Institute in Hamburg). Political parties and think tanks

are much more trapped in the present. A few governments have small teams looking into the distant future—for example in Singapore and Finland. But in general, although there is heavy investment in technological imagination and futures—much of it in Silicon Valley—there is far less on social possibilities. This is one reason why so much of Europe’s public now fear the future and expect their children to be worse off than them.

I’m interested in the role the arts can play. Claims that the arts can be prophets of the future, trailblazers of a future society, are quite wrong, and based on misunderstanding—though commonly articulated over the last two centuries by everyone from Percy Bysshe Shelley (who called poets the “unacknowledged legislators of the world”) to Joseph Beuys (who claimed that “only art is capable of dismantling the repressive effects of a senile social system that continues to totter along the death-line”). I can think of no work of art of the last 50 years that described or defined a better future for our society.

But what the arts are uniquely well placed to do is other essential work. I believe that some of the methods of creativity and design need to be integrated with the social sciences and the work of policy design. Remarkably little of this happens now—yet that cross-pollination was precisely what fuelled previous renaissances.

The arts can bear witness and warn—as so many are doing in relation to climate change. They can transform our perceptions. They can explore possibilities, both good and bad, as so many are doing with AI and data. And they can help large numbers to take part in the work of social exploration. Here are three examples.

Bearing witness: climate change

Climate change is now the most visible big crisis, prompting an extraordinary range of artistic responses. Most try to bear witness to what’s happening. Olafur Eliasson’s blocks of ice melting in city squares vividly make people think about climate change as a reality, not an abstraction. A similar effect is achieved by Andri Snær Magnason’s plaque to commemorate a lost glacier in Iceland or the World Meteorological Organization’s short videos presenting fictional weather reports from different countries in the year 2050: “WMO Weather Reports 2050.” Others turn the medium into the message, re-using waste materials to signal the emergence of a more circular economy.Literature is also grappling with climate change. What one author called ‘socio-climatic imaginaries’ can be found in novels such as Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife and Kim Stanley Robinson’s Green Earth (both from 2015) which go beyond the eco-apocalypse to examine the multiple interactions between nature and social organisation. Kim Stanley Robinson has spoken of science fiction as “a kind of future-scenarios modelling, in which some course of history is pursued as a thought experiment, starting from now and moving some distance off into the future” and makes a good case that literature is better placed to do this than anything else. As the warning signs of crisis intensify we should expect all the arts to respond in creative ways, both warning and bearing witness but also pointing to how we might collectively solve our shared problems.

Investigating complex challenges

The second big crisis—in the sense of being both a threat and opportunity—comes from algorithms and a connected world. Here the role of the arts seems to be more about investigating complex challenges and dilemmas. Many fear that technology will destroy jobs, corrode our humanity and our ethics. So it’s not surprising that we’re seeing an extraordinary upsurge of art works both using and playing with the potential of artificial intelligence. For some artists AI is primarily interesting as a tool—with GPT3 writing fiction; Google Tiltbrush and Daydream in VR; or the growing use of AI by musicians and composers. There are many wonderful examples of emerging art forms (like Quantum Memories at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne). But others are trying to dig deeper to help us make sense of the good and the bad of what lies ahead. Look, for example, at the work of Soh Yeong Roh and the Nabi Center in South Korea exploring ‘Neotopias’ of all kinds and how data may reinvent or dismantle our humanity. LuYang’s brilliant ‘Delusional Mandala’ investigates the brain, imagination and AI, connecting neuroscience and religious experience to our new-found powers to generate strange avatars.

AI’s capacity to generate increasingly plausible works of visual art and music is of course a direct threat to artists, and perhaps encourages a

hostile or at least sceptical response in works like Hito Steyerl’s projects exploring surveillance and robotics (like HellYeahWeFuckDie); Trevor Paglen playing with mass surveillance and AI; or Sun Yuan and Peng Yu’s ‘Can’t Help Myself’, on out of control robots. Others are more ambiguous. Ian Cheng’s Emissaries series imagined a post-apocalyptic world of AI fauna, while Sarah Newman’s work, such as the Moral Labyrinth, explores in a physical space how robots might mirror our moral choices, giving a flavour of a future where algorithms guide our behaviours.

Andreas Refsgaard’s work is playful in a similar vein, like the algorithm assessing whether people are trustworthy enough to be allowed to ask questions. Shu Lea Cheang’s work 3x3x6 references the standards for modern prisons with 3×3 square meter cells monitored continuously by six cameras, using this to open up questions about surveillance and sousveillance, and the use of facial recognition technologies to judge sexuality (including in parts of the world where it’s illegal to be gay). Kate Crawford’s fascinating project on the Amazon Echo (now at MOMA) is another good, didactic example, revealing the material and data flows that lie behind AI.

Each of these brings to the surface the opaque new systems of power and decision that surround us and the hugely complex problems of ethical judgement that come with powerful artificial intelligence.

Advocating for change

The third, slow-burning crisis concerns inequality in all its forms, at a time when power and wealth have been even more concentrated than ever in the hands of a tiny minority. The arts have always played a central role in advocating for greater equality, from the feminist utopias of the 18th century to the revolutionary films and murals of the 20th. They have also, of course, been bound up with wealth and power, dependent on kings and patrons, and today on the super-rich. The world of arts is now inescapably bound up with the many battles underway over gender, race, sexuality, and the responsibilities of institutions—sometimes bearing witness, sometimes investigating, but often acting as advocate. A striking example is the way around the world the Black Lives Matter movement sparked an extraordinary rethink. An interesting recent example is the transformation of the public statue of Robert E Lee in Richmond, Virginia, now covered with a growing forest of slogans and the names of victims of police violence. Many arts institutions are now being held to account for their treatment of historical memory, their links to slavery (like the Tate Gallery in the UK), and the connections of the arts establishment to the more malign features of contemporary capitalism. A good example is the work of Forensic Architecture challenging the role of the then vice-chair of the Witney Museum over his company’s role in making tear gas, a rare example of challenging elite power in the art market.

The top end of the arts market is now entwined with the world of fashion and the lives of the ultra-rich—a symptom more than a solution of what’s gone wrong with the world. High-end art generally favours forms of art that are abstract or ambiguous, paying lip service to equality but avoiding anything too specific, and now plays with new financial devices like NFT to commoditise art as a luxury good.

But a radically different energy is now coming from the bottom up, with a demand for the arts to be more engaged and more accountable. My sense is that this is fast becoming a generational divide, with an older generation reasserting the artist’s autonomy and freedom from accountability, and taking for granted a world of patrons and galleries not so different from a few centuries ago, and a younger generation no longer convinced that this is right for our era.

So art can thrive on crisis and can help foster a much needed renaissance. It can bear witness, explain and provoke. Many sense that a period of relative stability may be coming to an end. The first half of the 20th century brought world wars, and revolutions from Russia to China. Europe had far too much history! But history then slowed down—in good ways for much of the world. The Cold War froze

international affairs, and the period after its end brought far fewer big wars and fewer revolutions, even as parts of the world descended into civil war.

The 21st century by contrast appears set to see history accelerate again, with a looming confrontation between the US and China, the rising pressures of climate instability and the fragility of a world more dependent on networks and machine intelligence.

That may or may not be good for the arts. Harry Lime’s comment on Switzerland doesn’t quite fit today’s world, where the countries producing the most successful artists are generally stable and prosperous (Germany, the US…) rather than steeped in crisis and civil war (Congo, Afghanistan…).

But perhaps a little discomfort is good for the arts, and may better help them to help us make sense of the crises around us and to sensitise us to what’s not obvious. That may also prompt them to work harder to be part of the solutions rather than part of the problem and to help us to be actors not just observers.

Geoff Mulgan

Sir Geoff Mulgan is Professor of Collective Intelligence, Public Policy & Social Innovation at University College London (UCL). He was CEO of Nesta, the UK’s innovation foundation from 2011-2019. From 1997-2004 Geoff had roles in UK government including director of the Government’s Strategy Unit and head of policy in the Prime Minister’s office. Geoff advises many governments, foundations and businesses around the world. He has been a reporter on BBC TV and radio and was the founder/cofounder of many organisations, including Demos, Uprising, the Social Innovation Exchange and Action for Happiness. He has a PhD in telecommunications and has been visiting professor at LSE and Melbourne University, and senior visiting scholar at Harvard University. Past books include ‘The Art of Public Strategy’ (OUP), ‘Good and Bad Power’ (Penguin), ‘Big Mind: how collective intelligence can change our world’ (Princeton UP) and ‘Social innovation’ (Policy Press).

Picture © NESTA

Poetics in the Remaking of Europe

Writer, cultural activist and Emeritus Professor of Literature at University of East Anglia

Poetics in the Remaking of Europe

In 1951 the German philosopher, Theodor Adorno, published an essay called ‘Cultural Criticism and Society’. One remark in it, often taken out of context, made the essay famous: “After Auschwitz to write a poem is barbaric.” Whatever controversies it provoked, and however much Adorno subsequently changed his thinking about the relation between poetry and society, his comment remains emblematic of an important intuition. Language, and its expressive potentials, are not immune from historical events. Language has a distinctive life and social being, a life which can be enhanced, damaged or, in some of its forms, made obsolete. Violence threatens the life of language as it threatens other forms of life.

It is worth recalling the context that provoked Adorno’s remark. The holocaust remains at its dark centre, but, between 1939 and 1945, 36 million Europeans lost their lives in war related deaths. Many of the dead were civilians. The loss of life amongst Russians was greatest and more people died in eastern than in western Europe. But, however you analyse the numbers, what happened was probably the greatest act of human self-slaughter in history.

We may live in ignorance of these numbers and their implications. Or we may know about them and choose to ignore them. Or we may remember them in terms of certain images that we think are very much of the past: ruined cities, vast numbers of refugees, the dead and the scarcely living bodies of the Holocaust. That was Europe then and we live in a different place now. Wasn’t the post-war European renaissance precisely to do with the construction of a political order expressly designed to keep the peace? Hasn’t this been its most durable achievement?

We can answer those questions in different ways. One response might acknowledge that Europe had to come close to annihilation in order for that peace to be constructed at all. The memory of violence had to stay vivid for political energy and ambition to be directed towards the creation of a peaceful order. Now that memory has diminished, an important question for the next European renaissance is how the impetus for peace-making will be maintained. Another response, amongst the many causes of the violence that led to the slaughter of 1939-45, was a way of talking about the world that emphasised a wounded nationalism, that identified threats in alien others, and sought solutions in authoritarian leaders. Different media and different contexts were involved from films to newspaper articles to informal conversations.

These diverse means of communication created a multiplier effect. Xenophobia, racism and authoritarianism became the focal points of a collective imagination. Whatever else may have changed since this period, the thought that these ways of talking have been overcome in a new peaceful Europe is clearly false. If anything, they are on the rise, but in a way that still seems oddly oblivious to their possible consequences. A new European renaissance needs to take account of this fact: the way we talk to each other is consequential. It’s one of the many ways that we make the world we live in.

Some commentators at the time of the European conflagration were sensitive to this linguistic dimension. The English writer, George Orwell, was one. He saw that the totalitarian regimes that caused such havoc needed to control language and, by their control, to gaslight whole populations in order to maintain power. Albert Camus, Hannah Arendt, and Ceslaw Milosz all shared a similar sense of the importance of the way we talked to each other and our capacity to treat each other humanely as ends in themselves and not just means to an end.

Adorno was concerned with the violence that could be done to language, Orwell with the violence (and control) that certain kinds of language enable. For both, this heightened their sense of the conditions in which language might live or become dead and

deadening. Orwell valued a plain clear style as the condition of language’s vitality. Adorno valued the dialectical potential of a language that could put in question what it was saying and how it was saying it. Both opposed the use of jargon and the tendency of language to congeal into fixed vocabularies and routine gestures. All large organisations, the EU included, have a tendency to speak in ways that Adorno and Orwell opposed. The corporate speech of the early 21st century unconsciously echoes the language world of Orwell’s 1984 in its repetitiveness, its tendency to settle into slogans, and its closing down of thought in the name of consensus. But how might we find alternatives? This will importantly depend upon our own inventiveness with language and a willingness to give up on certain forms of ‘authoritative speaking’ that seem increasingly threadbare to those on their receiving end of them. Our own inventiveness can draw on many resources as we imagine how we might speak to each other in ways that are both democratic and expressive. Europe invents itself through many languages and not just one. In this repeat it is a little like another multilingual society, India. How we respond to this reality not as a deficit or a problem, but as a source of cultural enrichment and opportunity is one challenge for the next European renaissance.

For Merleau Ponty le langage parlant is a creative state, but it also affirms and recreates a social bond. It becomes what he describes as a “gesture of renewal and recovery which unites me with myself and others.” While he finds examples of this kind of language in literature it is by no means confined to a specialised form of creativity. The experience of “renewal and recovery” occurs for the speaker and the listener, for the individual and the collective. To utter le langage parlant is a potential in all of us, but one that circumstance can easily damage or restrict. It also marks the moment when language comes alive.

The first European renaissance marked a great transition in language in its affirmation of the expressive power and the literary dignity of different vernacular languages that were destined for a while to become the different national languages of Europe. The next renaissance will perhaps move in another direction, one that has been described as a colonial phenomenon, creolisation, where different languages and cultures mix and mingle. How we talk to each other and in what language or languages will become of ever greater importance. A ‘poetics for Europe’ will foster the conditions for a langage parlant made out of the interaction between different languages and cultures. One of its hallmarks will be the understanding that in saying something we are always doing something and that one of the things we are doing is recreating or dissolving the conviviality that can connect us one to another.

Jon Cook

Jon Cook is a writer, cultural activist and Emeritus Professor of Literature at the University of East Anglia. He was educated at Cambridge University and the University of East Anglia. He has published a number of books and essays that, in different ways, focus on the question of what makes language creative. From 2008-2017 he was on the governing body of the Arts Council for England. He has taught at universities in the US, Europe and India and is currently involved in a project to create an arts and humanities curriculum for the 21st century. In 2021 he was appointed an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. He currently lives near Stroud in Gloucestershire and hopes it will not be too long before the UK rejoins the EU.

The next renaissance will be globalised

Johannes Ebert, Secretary General/ Chairman of the Board of Goethe-Institut; Nico Degenkolb, advisor for Cultural and Creative Industries projects at Goethe-Institut Head Office, Munich

The Next Renaissance Will Be Globalised

Shaping the past, changing the future?

Renaissance, Reformation, Enlightenment, Modernity: these terms for epochs of progress and awakening continue to shape the collective identity of Europe and of the Western world to this day. Their achievements are rightly pointed out and their pioneers and representatives remembered.

However, what has increasingly entered public discourse and thus collective consciousness in recent years is a fundamental ambivalence that characterises Europe’s history of progress in the modern era—on the one hand, a claim to values shaped by humanism, and on the other, a lived practice that all too often contradicts the ideals formulated.