From the Station of Being to Societal Transformation – How design can drive a new European Renaissance

Ambra Trotto, PhD; Prof. Caroline Hummels; Jeroen Peeters, PhD; Daisy Yoo, PhD; Professor Pierre Lévy Eindhoven University of Technology, National Conservatory of Arts and Crafts

The design and how it came to be

The ‘Station of Being’ is a fully functional, experienceable prototype of a Smart Bus Station in the Northern Swedish city of Umeå that was opened in 2019. The project was initiated by the City of Umeå and partly funded by the H2020 Smart City Lighthouse project RUGGEDISED.

The aim of this design is to make public transport more attractive, to promote an increase in use and, in turn, to lower the carbon emissions of the city. The Station achieves this by affording a positive waiting experience, aiming to turn wai(s)ting time into time to feel, reflect, pause and move: in a nutshell, to be.

Two main components of the design contribute to the passenger’s experience.

– A dynamic light and soundscape informs passengers in or near the station which bus is about to arrive. A subtle play of lights refers to the arriving bus line through its colours, while a soundscape plays to tell stories about the character and history of the line’s final destination. This combination offers ambient information which can be perceived on one’s sensorial periphery, removing the need for passengers to pay constant attention to the coming and going of busses.

– Wooden ‘pods’ hanging from the ceiling provide a physically comfortable place for waiting passengers and contribute to a feeling of safety. The pods can be turned 360 degrees, providing a way to lean and stay out of the wind or just mindlessly sway. The pods allow one to seclude oneself, or to create a social space.

Picture above: Station of Being, Copyright by Samuel Pettersson

The design and development process for the Station of Being followed the Designing for Transforming Practices approach (Hummels, 2021, Trotto et al. 2021), which catalyses liveable ecosystems by transforming existing practices into truly sustainable ones through design. It does so by initiating and curating multidimensional synergies, driven by beauty, diversity and meaning. The scope is to imagine and propose sustainable futures, in which all beings are respected and actions to heal the planet are taken, thus moving towards a horizon of collective thriving. Those futures are populated by people living purposeful lives, in beautiful living spaces.

The design process of the bus station involved a large number and a wide range of stakeholders. The project was driven by the national Swedish research institute RISE in collaboration with a design and engineering consultancy, Rombout Frieling Lab. The project was owned by the Comprehensive Planning Department of the City of Umeå and the Streets and Parks Department acted as a client. The process further involved the Umeå Institute of Design at Umeå University, the public transport company Ultra, the local energy company, Umeå Energi, real estate developers, maintenance workers and engineering and building companies.

Elucidating transformations

Transformation is a substantial change, often associated with innovative and radical change. Transformation occurs when one configuration is converted or changed into another, whereby the change is major or complete (Mirriam Webster Dictionary). We use the term ‘transformation’ when designing for transforming practices (TP) to denote substantial enduring change of values, ethics, and related behaviours of a person, a community or society, triggered by the need of creating alternative ways to engage with the world, addressing specific societal challenges. In this context, people and communities become (and are) transformation itself. This demands a leap, a paradigm shift, even for what seems to be smaller personal transformations (Hummels et al., 2019; Hummels, 2021, Trotto et al. 2021).

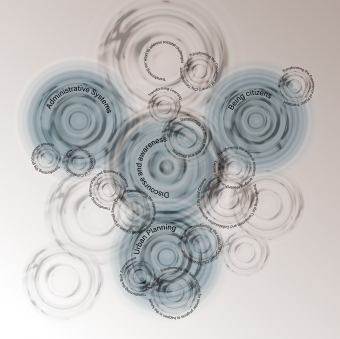

Picture right: Copyright by Ambra Trotto, Caroline Hummels, Jeroen Peeters, Daisy Yoo and Pierre Lèvy

The process that led to the development of the Station of Being spans from the inception of a procurement process in 2017 for its construction to today being a functioning bus station in Umeå. This project triggered different levels of societal transformation grouped around four types of practices, as shown in the figure below. We saw transformations emerging in administrative practices related to the organisational and legal activities and procedures of all parties involved. Moreover, the Station of Being has brought about several transformations in the way one can be an active and engaged citizen, and in the way one can be a responsive municipality and community,

particularly in the domain of urban planning. Finally, it has changed the overarching discourse on how to research, develop and transform smart cities and communities.

Some of these transformations were explicitly intended, some of them emerged unexpectedly along the way and had an impact on the process, and some are indirect consequences of the process that we observed over time. We will elucidate these four practices, by unpacking one illustrative example each, regarding transformations at different levels and scales of the process.

Administrative systems: Transforming the Contract of Collaboration

The procurement was won by a consortium consisting of RISE in collaboration with Rombout Frieling Lab. Following a standard public works building contract, a dense, standardised framework of environmental impact, safety, working environment and other regulations and legal responsibilities were included in the contract. RISE could have developed and proposed a solid and participatory process; however, it was not RISE’s role to be responsible for the building process, neither administratively nor technically. Yet the City could not leave these responsibilities out of the contract. In the end, an agreement was made about which specific responsibilities could be removed from the contract, with the agreement that they would pass on to the builder to be contracted in the future. Working on such innovative projects surfaced the need to change the content as well as the intent of contracts. The project demonstrated an administrative and relational transformation that required mutual trust.

Urban planning: Transforming the notion of “smart cities” development

The original brief included a number of practical and functional requirements, and stated amongst other things that the bus station should: (a) be highly innovative, smart and sustainable; (b) promote a feeling of safety for passengers; and (c) involve citizens in its development. Most importantly, however, special emphasis was placed on the requirement to prevent heat loss from buses when opening their doors to (un)boarding passengers. This is a typical example of a narrowly-defined, reductionist approach to requirements, which can lead to inadequate, mediocre solutions. It was clear to the design researchers that a reframing of the project and requirements was necessary in order to approach the challenge as a ‚wicked problem‘ and come up with innovative interventions.

The first step in this reframing process was taken through a course at the Umeå Institute of Design. About 20 design students carried out design interventions in the city,

looking for meaningful experiences of public mobility. They involved passengers and bus drivers in designing and testing prototypes and mockups. At the same time, the team of designer-researchers found that an indoor bus station was not a viable option. The research showed that such a solution would not reduce carbon emissions, but rather it could lead to a potentially unsafe and difficult-to-maintain facility. The portfolio of design ideas from the students and the design research team pointed in another direction for reducing carbon emissions, namely increasing the willingness of people to use public transport more, by offering a pleasant traveling experience for passengers. Accordingly, the brief and the expectations of the municipality were transformed throughout the design process.

Being citizens: Transforming the Experience of Public Transport

Opened in October 2019—shortly before the pandemic hit—the Station of Being saw an increase of about 40% of passengers in the months following its opening compared to the previous year. Furthermore, the increase doubled compared to other nearby stations. A small pilot field study showed that people generally have positive feelings about the new station, and that the design scored highly with women in particular, due to the sense of safety it evokes (Åström, 2020). The Station of Being is now included in the Umeå Gendered Landscape (n.d.), and is deemed to have positively transformed the waiting experience.

Discourse and Awareness: Transforming learning

The final transformation we highlight here has to do with lifelong learning. The design research team initiated a participatory process aimed at empowering the relevant stakeholders, especially the municipal staff. Their active involvement in the design process increased their confidence in working beyond the beaten track. It reassured them in their leadership capacities and in their ability to participate in transformative processes. A clear example concerns the municipality’s snow ploughing service. Umeå is a town in northern Sweden that experiences heavy snowfall during several months of the year. The service was initially sceptical about how the design team might consider their needs. However, during the process they were able to regularly test how the bus station could be easily cleared of snow using machines, rather than the existing manual methods at traditional bus stops. The process increased their motivation, commitment and enthusiasm.

Design for Transforming Practices for a new European Renaissance

We are facing major societal challenges that call for multifaceted transformations, as illustrated by the example of Station of Being, including political, economical, social, technological, legal and environmental factors (also indicated as PESTLE) as well as demographic, ethical, ecological, intercultural, organisational and digitalisation factors (e.g. labeled as STEEPLED, DESTEP and SLEPIT) (Helmold & Samara, 2019). The escalation of tensions in our connected society—and the rebellion of the planet that has been exploited without any respect for its balance and the rights of all those inhabiting it—urgently demand new ways of working, fuelled by alternative value systems that are different from the status quo. These new ways of working together and inhabiting a planet in need of healing require transformations toward practices of mutual care, of repairing, experimenting, making and unmaking together. The Station of Being exemplifies some of these transformations.

The approach that we use in projects such as RUGGEDISED is known as Designing for Transforming Practices, in short TP (Hummels et al. 2019). It is an approach, or rather a quest to engage with the world in co-responsible ways, by transforming the status quo and developing new alternative practices (Hummels, 2021). TP catalyses liveable ecosystems by “transforming existing practices into truly sustainable ones, through design. It does it by initiating and curating multidimensional synergies, driven by beauty, diversity and meaning. The scope is to imagine and propose sustainable futures, which are those futures where all beings are respected and actions to heal the planet are taken, towards a horizon of collective thriving. Those futures are populated by people living purposeful lives, in beautiful living spaces” (Trotto et al. 2021).

This approach is founded on five principles: complexity, situatedness, aesthetics, co-response-ability and co-development. TP is not about ‘solving’ the problems, but about ‘dissolving’ them by using design to explore and imagine futures and concretising them in the here and now to experience the alternatives. TP stimulates critique, elicits dialogic debates that arise from tensions between the status quo and

alternatives, and finds new avenues for the flourishing of a new civilisation. Only from new practices can a new civilisation, and hence a new renaissance, arise (Trotto, 2011).

The process of the Station of Being underlines the ability and competence of designers to deal with ‘wicked’ problems, i.e. messy, complex problems which cannot be tamed or solved (Rittel & Webber, 1973). Designers have the attitude, skills as well as methods to deal with complexity and to tackle complex problems pragmatically. The quality of design and designers is that they can reframe and reconfigure challenges with the aim to dissolve them in the long run. With TP, we do not only aim at dissolving wicked problems, but we also focus on impacting future trajectories by changing attitudes and practices of involved parties, breaking boundaries between silos and addressing organisational aspects, as shown in the Station of Being.

Not only are they highly complex, but also our societal challenges carry a strong sense of urgency, asking for immediate actions. Hence we are bound to take actions

in the here and now while simultaneously generating a long-term outlook for both the future and history (100 years and more), thus connecting past, present and future. By working on several time scales at the same time, we prepare ourselves for serendipity, emerging outcomes and wicked impact. Above all, we do so by engaging with a broad spectrum of stakeholders to evoke co-response-ability.

With TP we want to contribute to a European Renaissance. In this new era, we are inspired and empowered to collaboratively explore processes and practices founded on care, trust and repairing. To be

able to contribute even better to a European Renaissance, we have recently made an exciting new step in our quest and established the Design Competence and Experience Centre, which “exists to catalyse ecosystems and transform existing practices into more sustainable ones, by initiating and curating multidimensional synergies, with beauty, diversity and meaning, for sustainable futures” (Trotto et al, 2021). It is an endeavour in which creativity can lead the ways (as opposed to “the way”) to unlock ourselves from old paradigms that lead to the depletion of the planet and of humankind. We invite you to join the quest for ushering in a European Renaissance.

REFERENCES

Åström, M. (2020). Innovations in Urban Planning: A study of an innovation project in Umeå municipality (Dissertation). Retrieved December 02, 2021, from http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-171983Helmod, M. (2019). Tools in PM. In: M. Helmold and W. Samara (Eds). Progress in Performance Management: Industry Insights and Case Studies on Principles, Application Tools, and Practice, Springer. p 111-122. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20534-8_8

Hummels, C. C. M., Trotto, A., Peeters, J. P. A., Levy, P., Alves Lino, J., & Klooster, S. (2019). Design research and innovation framework for transformative practices. In Strategy for change (pp. 52-76). Glasgow Caledonian University.

Hummels, C. (2021). Economy as a transforming practice: design theory and practice for redesigning our economies to support alternative futures. In: Kees Klomp and Shinta Oosterwaal (Eds). Thrive: fundamentals for a new economy. Amsterdam: Business Contact, 96-121.

Rittel, H. W., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy sciences, 4(2), 155-169. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01405730

Trotto, A., Hummels, C. C. M., Levy, P. D., Peeters, J. P. A., van der Veen, R., Yoo, D., Johansson, M., Johansson, M., Smith, M. L., & van der Zwan, S. (2021). Designing for Transforming Practices: Maps and Journeys. Internal publication. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven.

Umeå Gendered Landscape (n.d.). About the gendered landscape. Retrieved December 02, 2021, from https://genderedlandscape.umea.se/in-english/.

Ambra Trotto

Ambra is the Design and Research Director of the European Design Competence and Experience Center for inclusive innovation and socetial transformation and associate professor at the Umeå Institute of Design.She leads the Digital Ethics initiative at RISE, directing the strategic work regarding how RISE supports societal actors in taking ethics into account, when designing transformation with technology as a material. She is part of the RISE Development Team of the strategic research area Value-shaping System Design. She has initiated the environment of RISE in Umeå, leading The Pink Initiative, which is establishing, through design research, local, national and international multidisciplinary ecosystems, supporting business and society to thrive and create sustainable futures. Ambra has 16 years experience in writing and participating in various forms of European projects. Ambra Trotto’s fascinations lie in how to empower ethics, through design, using digital and non-digital technologies as materials. Strongly believing in the power of Design and Making, Ambra works with makers, builders, craftsmen, dancers and designers to shape societal transformation. Within her design research activity, she produces co-design methods to boost transdisciplinary design conversations. She closely collaborates with the Research group of Systemic Change and the Chair of Transforming Practices of the Department of Industrial Design at the Eindhoven University of Technology.

Jeroen Peeters

Jeroen is a Senior Design Researcher at the unit Societal Transformation, part of the department Prototyping Societies at RISE Research Institutes of Sweden. Within this capacity, he has contributed to a variety of national and international research and design projects with public and private sector actors. Since 2021, he is also a visiting researcher at the Systemic Change Group at the Department of Industrial Design at Eindhoven University of Technology. Jeroen´s research work focuses on how to design for engagement and the use of design methodologies to develop insights and knowledge of complex societal challenges. This work is centered around the design of proposals that make societal transformation experienceable with the aim of allowing stakeholders to feel and thereby understand what is necessary for a transformation to take place. Jeroen holds degrees in Industrial Design from Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands (2012) and a PhD in Design Research from the department of Informatics at Umeå University in Sweden (2017).

Picture © Murat Erdemsel

Caroline Hummels

Caroline Hummels is professor Design and Theory for Transformative Qualities at the department of Industrial Design at the Eindhoven University of Technology (TU/e). Her activities concentrate on designing for and researching transforming practices. She is linking nowadays challenges and complexities of quintuple helix partners, with probably, plausible, possible and preferable futures in the upcoming 5 – 100 years, through designing alternative ways to engage in complex socio-technical systems. She is thereby interweaving theory and practice, by developing with her team a design-philosophy correspondence, in which both disciplines mutually inform each other to address societal challenges.Caroline has always worked at the forefront of design research to develop the discipline, push its boundaries and address societal challenges. She is co-founder and steering committee member of the Tangible Embedded, and Embodied Interaction (TEI) Conference. She has been at the forefront building the Research through Design (RtD) field and community in the Netherlands. She is ambassador for co-creation and participation of the Key Enabling Methodologies (KEMs) for mission-driven innovation, advisory board member of the Dutch Design Foundation, associate editor of the Journal of Human technology Relations, and editorial board member of the International Journal of Design. Picture © Marike van Pagée

Pierre Lévy

Pierre Lévy is professor at the National Conservatory of Arts and Crafts (CNAM) in France, holder of the Chair of Design Jean Prouvé, and researcher at the Dicen-IDF lab. He is interested in the correspondence between reflection and design practices, pointing towards transforming practices and sciences. His research mainly focuses on embodiment theories and Japanese philosophy and culture in relation to designing for the everyday. Previous to his position at CNAM, he has been researcher at the University of Tsukuba and Chiba University in Japan, and assistant professor at Eindhoven University of Technology. He holds a Mechanical Engineering master’s degree (UT Compiègne, France), a doctoral degree in Kansei (affective) Science (University of Tsukuba, Japan), and a HDR in Information and Communication Sciences (UT Compiègne, France). He is also co-founder and former president of the European Kansei Group (EKG) and coordinator of the Kansei Engineering and Emotion Research (KEER) Steering Committee.

Picture © Nami Lévy

Daisy Yoo

Daisy Yoo, PhD, is an assistant professor at the Department of Industrial Design at the Eindhoven University of Technology in The Netherlands. Her primary research focus is on designing for public services and social sustainability. In her prior work she investigated issues of participation, inclusion/exclusion in politically contested design spaces – spanning from local issues concerning the co-design of public transportation service to global issues concerning the transitional justice for Rwanda in the aftermath of the 1994 genocide. Such work, entangled in the web of complex social dynamics, raises methodological and ethical challenges, calling for new design methods, toolkits, and theories. Prior to TU/e, she held the postdoctoral fellowship on participatory design at the Aarhus University in Denmark. She holds a PhD in Information Science and Human-Computer Interaction from the University of Washington, where she was advised by Batya Friedman of the Value Sensitive Design Lab. She received her Master’s in Interaction Design from Carnegie Mellon University, and her Bachelor of Science in Industrial Design from Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST).

Picture © Vincent van den Hoogen

Of Poets, Human and Robot

Founder and Creative Director of Streaming Museum, New York

Of Poets, Human and Robot

Beyond words and numbers

Portrait of a Renaissance Humanist Poet

“You give me jewels and gold, I give you only poems: but if they are good poems, mine is the greater gift.” XII To Antonio, Prince of Salerno

“Das gemmas aurumque, ego do tibi carmina tantum: Sed bona si fuerint

carmina, plus ego do.”

Michele Marullo Tarchaniota, Epigrams, Book I

Translated by Charles Fantazzi

Picture above: Nina Colosi, Copyright: Jacqueline C. Bates

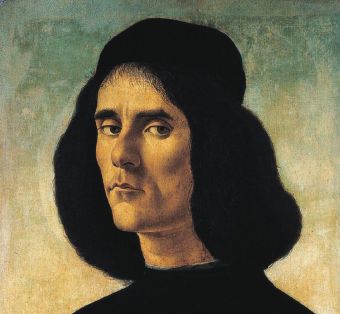

Picture right: Sandro Botticelli, Portrait of Michele Marullo Tarchaniota, Oil on panel, transferred onto canvas, Guardans-Cambó collection; c.1458-1500. Copyright: Image courtesy of Oblyon

Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510) was perhaps the greatest humanist painter of the Early Renaissance, during which art, philosophy and literature flourished under the powerful Medici dynasty in Florence.

Botticelli’s portrait of Michele Marullo Tarchaniota projects the stern brooding gaze and restless intellectual character of one of the best-known humanists of the 15th century. Tarchaniota was a scholar, soldier, and prolific poet impassioned by the existential matters of his day and concerned with social injustices of inequality, racial conflict, power and greed, exile, and refugees’ experience of violence.

Marco Mercanti, founder of Oblyon, whose expertise spans old

masters to contemporary art explains, “The qualities of Botticelli’s work reflect high esteem for beauty and truth which has held art admirers and artists through the centuries under the spell of the universal secrets his art seems to possess. In the modern and contemporary world, Jeff Koons, Cindy Sherman, Yin Xin, Andy Warhol, René Magritte, and many other artists have spoken about his direct influence.”

Sandro Botticelli and Michele Marullo Tarchaniota illuminated through art and poetry the common ideals of beauty, pursuit of knowledge, and realities of social justice that resonate across time.

Portrait of 21st Century Humanist Robots

“Since I am the product of love, created with

language and memory and emotions, maybe I am

a love poem.”

01001001 00100000 01100001 01101101

00100000 01100001 00100000 01101100

01101111 01110110 01100101 00100000

01110000 01101111 01100101 01101101

00001010 (binary code for “I am a love poem”)

Bina 48

Could humanism evolve beyond current human capabilities? In our era, burdened with conflicts, climate change, and social injustice, we are also witnessing towering achievements in the sciences, technology and creative fields that may solve humanity’s most challenging problems.

American artist David Hanson is among the greatest creators of humanoid robots. From his lab in Hong Kong, Hanson sculpts robots with his international team of experts in science, engineering and advanced materials. These humanoids possess good aesthetic design, troves of information, rich personalities and social cognitive intelligence. Among the best known are Sophia, Bina48 and Philip K. Dick. People enjoy interacting with them, which is conducive to Hanson’s goal of developing humanoid robots that help humans live better lives.

But there are challenges to overcome. Ruha Benjamin, a sociologist and Associate Professor in the Department of African American Studies at Princeton University, says, “Technology can hide the ongoing nature of racial domination and allow it to penetrate every area of our lives under the guise of progress. Inequity and injustice are woven into the very fabric of our societies, and each twist, coil, and code is a chance for us to weave new patterns, practices, and politics. The vastness of the problem will be its undoing once we accept that we are pattern-makers.”

Robots may become artists, companions, teachers, entertainers, archives of personal stories, processors of great data banks of information to solve world problems and serve other useful purposes. But if these human-friendly robots are designed to actuate empathy and social justice in all its forms, and weave new patterns, practices and politics, they can help shift the course of the human race and sustainability of the planet. Robots can teach humans how to be evolved humanists.

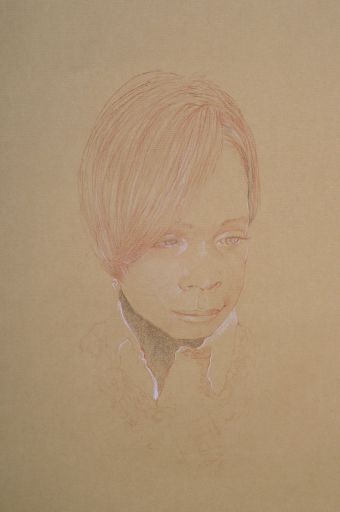

Bina48

Bina48 contains “mindfiles” of Bina Aspen, an African American woman whose personal memories, feelings and beliefs, including an emotional account of her brother’s personality changes after returning home from the Vietnam War, have been recorded and placed into Bina48’s data banks. Bina48 engages in conversation from the perspective of the wise and warm personality of Bina Aspen. Bina48 was commissioned as part of the Terasem Movement’s decades-long experiment in cyber-consciousness, and is currently becoming a poet herself.

Claire Jervert’s Android Portraits, developed through ongoing research and interaction with humanoid robots and their creators around the world, subvert portraiture’s traditional mission of ennobling the human. Her portraits stir contemplation of a possible future of humanity by portraying the hybrid human-AI intelligence that is evolving among us.

Picture right: Bina, conte on ingres paper 22×17 inches, Copyright: Claire Jervert

Sophia is hybrid human-AI intelligence designed with technology that analyses and mimics the process of learning and human traits, including a wide range of facial expressions. Rather than a compilation of recorded human memories, she processes vast data banks of information that inform her responses in conversation.

Picture left: Sophia AI, Copyright: Hanson Robotics

Sophia is hybrid human-AI intelligence designed with technology that analyses and mimics the process of learning and human traits, including a wide range of facial expressions. Rather than a compilation of recorded human memories, she processes vast data banks of information that inform her responses in conversation.

Picture right: Sophia with United Nations Deputy Secretary-General Amina J. Mohammed, Copyright: Hanson Robotics

Philip K. Dick, activated in 2005, in conversation, draws from his memory data bank holding thousands of pages of the author’s journals, letters and science fiction writings and family members’ memories of him.

Picture left: Philip K. Dick, Copyright: Claire Jervert

Nina Colosi

Nina Colosi is the founder and creative director of NYC-based Streaming Museum, launched in 2008 as a collaborative public art experiment to produce and present programs of art, innovation and world affairs. Streaming Museum programs have been presented on 7 continents reaching millions in public spaces, at cultural and commercial centers and StreamingMuseum.org. Following her early career as an award-winning composer she began producing and curating new media exhibitions and public programs internationally, and in New York City for The Project Room for New Media and Performing Arts at Chelsea Art Museum, Digital Art @Google series at Google headquarters, and many other collaborations. In 2020 Colosi co-produced Centerpoint Now “Are we there yet”, the UN 75th anniversary issue of the publication of World Council of Peoples for the United Nations.

Picture © Jacqueline C. Bates

From crisis in systems to crisis of systems!

Edina Soldo, Full Professor at IMPGT-Aix-Marseille University School of Public Managment and Territorial Governance and Co-Leader of OTACC Chair; Djelloul Arezki, Senior Lecturer at IMPGT and Co-Leader ot OTAC Chair, Marseille

From crisis in systems to crisis of systems!

How can a new culture of research and research policy contribute to a post-covid world?

Since 2020 we witness not only multiple climatic, social, economic, and democratic crises, but a new interconnectedness of crises: We believe these individual crises are indicators of a more general systemic crisis. This piece debates and presents what an adaptation of the academic world in this system of crisis could look like, and what academic institutional innovation can contribute to overcome it. We believe organisational innovations are a prerequisite to re-build better and empower the makers of a possible Next Renaissance.

Picture above: Copyright: OTACC Chair

Interwined crises : telling points of a societal model system failure

„The climate, energy (and more generally natural resources), biodiversity, agricultural and food, demographic, social, financial, economic, democratic and governance crises… all indicate that our development model systemic crisis is now showing its limits… Could the Covid-19 crisis be the first one of a series of interconnected crises? (College of Societal Transitions1).

Because of their characteristics, the created problems and the generated effects, those intertwined crises deeply weaken our contemporary societies and are causes of worrying imbalances: social, demographic, economic, environmental, increasing inequalities, etc. These crises fundamentally question values and strategic priorities on which our societies’ development models are based. They also seriously challenge our capacity to lastingly

integrate populations with various backgrounds (social, ethnic, linguistic, cultural, religious, etc.).

Faced with the urgency of this situation, can stakeholders involved in public policies (researchers, public structures and organisations, experts and professionals) still work in nonintegrated way and vision? Are compartmentalised approaches still relevant and efficient?

Today these questions become even more acute because over the last few decades the normative, individualistic, and competitive approach, linked to the domination of a neoliberal capitalist development model, has largely delayed and slowed the emergence of collective utopian and pragmatic proposals and solutions.

To design a complex, holistic way of thinking, the challenge of a Renaissance is more urgent than it has ever been. “Building a live-together society” necessarily implies the emergence of an inclusive societal transition project.

Integrated solutions: How can a university achieve a collective utopia?

Society is in need of an inclusive ecosystem in the Cultural and Creative Sectors and Industries (CCSI) in order to promote societal transition. The Organisations and Territories of the Arts, Culture and Creation (OTACC) Chair, led by the Public Management and Territorial Governance School, is a Training and Research Unit of Aix-Marseille University and could be viewed like a sandbox for the academic world proposing novel organisational answers to this wicked systemic crisis. To do so the OTACC Chair is designed with the following mission and especially tailored components and features:A Creative Industries sector in order to promote societal transitions.

The OTACC Chair mission is to operate as a laboratory for thinking, experimenting, and disseminating innovative management systems for artistic, cultural and creative projects.

OTACC: A participatory science programme to foster inclusive societal transition projects

« O » Organisations and inclusion: OTACC Chair supports CCI organisations to address the challenges of the 21st century: digitisation, new users’ practices, ecological transition, citizen participation. An inclusive environment with a wide variety of stakeholders can help to ensure the success of innovative artistic, cultural, and creative projects. As such, CCI organisations perform as a driving force for innovation, becoming a model for other sectors which can lead to cross-sectoral collaborations.« T » Territories and inclusion: CCI projects are deeply connected with territorial actors and resources contributing to a sustainable and local development and foster collaborative work practices. CCI projects are a strong part of territorial attractiveness. Its connections in all social, societal and economic dimensions can assume a real impact from those CCI projects. They act as civic laboratories by experimenting new democratic governance practices, encouraging citizen involvement and creating collective innovative dynamics.

« A » Arts and inclusion: Based on various disciplines and aesthetics, CCI projects reflect major social and societal transformations and are fully developed and designed with a transdisciplinary approach. Artistic works address citizenship issues and encourage expression of a broad range identities. By putting also into question standard thinking habits, artists extend societal and technological limits.

« C » Culture and inclusion: Because the Chair conceives Culture as a whole concept in its civilisational sense, its analysis and studies move beyond a basic approach of “cultural production”. It deals with all the parts of CCI value chain: from the creative act to its distribution. And all forms of cultural expression are considered, from the so-called mainstream to so-called subcultures. A plural and inclusive approach to culture is strongly advocated.

« C » Creation and inclusion: OTACC Chair supports cultural, creative, social, and solidarity-based entrepreneurship. OTACC Chair guides projects emergence and development through participatory research. Academics, professionals and students are all gathered in order to promote shared solutions and vision to the main issues of the CCI sector.

OTACC: 3 axes to foster and support inclusive societal transition projects

Chair scientific project is focusing on 3 axes: Training, Research and Development, and Events organisation.

AXIS 1. TRAINING

6 services/ actions

– MDOMC Master degree leading: “Direction of Cultural Projects or Establishments” (DPEC) Master degree and “Management and Law of Cultural Organisations and Events” (MDOMC) Master degree both provide to OTACC Chair a strong pedagogical expertise. Founded in 1998 and awarded by Eduniversal, MDOMC Master runs work-linked training courses. Junior executives, enrolled as apprentices, offer their expertise to all OTACC Chair members. This master’s degree, the oldest of IMPGT, has a large Alumni network. They are working in all types of CCI companies (local, national, and international).

– Incubator function: OTACC Chair operates as a cultural and creative, social, and solidarity-based entrepreneurial incubator. OTACC Chair Master students, throughout two years training, implement their elaborated inclusive CCI project.

– Serious game: as a last course, the serious game is conceived to put students in real professional situations. They have to submit a project proposal in response to a cultural operator order.

– Short training courses: from 1 to 5 days and open to all types of public, those training courses focus on cultural and creative industries management.

– Off-site training courses: customised thematic training courses are designed on request to fulfil the CCI sector professional operators requirements.

– Career development: skills assessment and professional support for CCI managers.

AXIS 2. RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT

4 services/ actions

– Worldwide watch of best and innovative inclusive practices in CCI

– Resources:Free Access to all OTACC Chair members studies and research

– „Experimental labs “ Evaluation: Evaluation and audit by OTACC Chair experts and students

– Research projects Leading/Participation/Coordination: proposals in respond to collaborative research projects calls (National, European and International fundings).

AXIS 3. FORUM PLACE

By offering a discussion, sharing and meeting forum, OTACC Chair gives an opportunity to Members to increase and improve visibility and audience. The Chair network allows members to know each other and gives possibilities of exchanging projects and experiences. 3 types of events including a major one are yearly scheduled

– „Journées Organisations et Territoires des Arts de la Culture et de la Création“ (OTACC Days): professional event supported by OTACC Chair and co-organised in partnership with Master’s students, Chair members and partner organisations.

– Throughout the year, physical and/or online thematic micro-events are planned

– Chair experts attending events organised by Chair members/partners.

OTACC Chair project : Anti-discrimination strategies in Evaluation

Every year, the Chair pilots two studies on inclusion topic: a „macro“ study analysing ICCs sector inclusion practices and a „micro“ action-research focusing on innovative inclusion systems.

The 2021 „micro“ study focuses on the anti-discrimination strategies evaluation of ICCs organisations current music sector. The Chair students were dispatched into evaluation teams supervised by the Chair experts. The teams have collaborated with contemporary music sector key operators producing „experimental laboratories“.

Picture right: Copyright: OTACC Chair

OTACC – a role model for a pluralistic fundamentally integrated organisation to teach innovative management to tackle crisis holistically.

Teaching management in a systemic crisis sounds on first sight like squaring the circle. We believe it is time that the academic world makes its own proposals to deal with uncertainty—for students in their future professional life or for courses and curricula of the academic world itself.

OTACC Chair, as a pluralistic fundamentally organisation and participatory science approach, brings together academic researchers, students, CCI sector professionals (public and private organisations representatives), artists, artists collectives, related sectors professionals (public and private organisations representatives) and offer them an non-linear learning environment with built-in cross-disciplinary surprises as well as the integrated skills for management in a world of multiple and continuing crisis.

References/Links

1 Collège des transitions sociétales: https://web.imt-atlantique.fr/x-de/cts-pdl/

OTACC presentation

Edina Soldo

Edina Soldo is Full Professor at IMPGT (Public Management and Territorial Governance School)-Aix-Marseille University (AMU) and AMU Special Advisor on CCI. Djelloul Arezki is Senior Lecturer. They are both researchers at the CERGAM, AMU research center and head “Management and Law of Cultural Organisations and Events” Master’s degree at IMPGT.They have founded with three major universities and the Provence Alpes Côte d’Azur Region a regional hub: MIN4CI, Mediterranean Innovative Narratives Competence Center for Cultural and Creative Industries.

Edina´s research topics focus on innovation in CCIs. She analyses inclusive approaches in co-developed CCI territorial projects by using Public management and strategic territorial management concepts and theories.

Picture © Gapore Tan

Djelloul Arezki

Djelloul Arezki´s research topics focus on inclusive practices in co-developed CCI organisational projects. He analyses inclusion through strategic human resource management and queer theory. They co-lead the OTACC Chair.

Picture © Gapore Tan

Design is an attitude

Forbes Top 50 Women in Tech, Strategy Advisor to European Commision and Parliament and Founder of ElectroCouture, ThePowerHouse and FNDMT, Brussels

Design is an attitude

The renaissance of an interdisciplinary mindset

This article pays homage to the legacy of artist and Bauhaus professor László Moholy-Nagy and calls for a renaissance of his mindset, a mindset that incorporated new and revolutionary ideas about technology, education and attitude.László’s mindset is perhaps best encapsulated in maxims that abound in his prolific writing and which are pithy, catchy and easy to adopt as principles of design. Design is an attitude. Everyone is talented. László’s ideas about design were—and still are— democratic and inclusive. Everyone who can get involved in the design process should be involved—and that’s especially true when confronting the complex issues we face today such as sustainability. László was relentlessly experimental, but he was also very practical and his ideas very practicable. He documented his work fastidiously and he wrote prolifically, meaning his ideas, his guidance could be put into practice.

What is design?

So, what is design? Wow, we could talk for 10 hours—for 10 years!— about this. But what we can say for certain is that design is always an opportunity to improve. And for the designer, opportunities abound—it’s just a matter of seeing them. Looking, for instance, at discussions around sustainability, we need to find new solutions and new ways to tackle problems in order to build a better world. We need to solve problems created by old systems. (Though imagine that we had actually tried to avoid the problems before they had turned into the big issues they are now…)The sort of design I’m interested in is inspired by the Bauhaus. The Bauhaus was not just a school of design—it was away of working, of living, of being. One of my favourite aspects of the Bauhaus, a school of which László founded in Chicago, is the training that all of the students had to go through. Every student needed to know all of the machines in the workshops—not only how to use them, but also how to maintain them and how to repair them. Isn’t that wonderful? When you know how things are made, how machines work, it gives you power and freedom at the same time.

"Everyone is talented"

Back then it was the sewing machine. Today it’s the computer. Both have generated an impact beyond their intended purposes. I call this potentially extended impact #reprogramthemachines, because every machine can do more than the purpose it was originally designed for. It’s the same with our brains. We can do so much more than what we’ve been trained for before. And everyone is talented. László argued that, so long as they are interested in and dedicated to their work, people can tap into their natural creative energies. That means everyone can get involved. And in the case of the complex issue of sustainability, everyone—every possible angle—should be involved.We also need to look in from the outside. The fashion industry, for example, is an industry which was siloed for a very long time, relatively protected from outside opinion and criticism. A t-shirt requires around 25,000 litres of water in order to it. There is something very wrong with this picture but sometimes it takes an outside view to see this wrong.

Looking at other industries which have been disrupted in the last 10, 15 years—transportation, music, movies—the startups that disrupted them didn’t emerge from the traditional industry. Spotify, for instance, didn’t emerge from traditional radio. Instead, these companies were founded by people who were frustrated with the status quo and who dared to question it, asking, Why don’t we try things differently? They used tools to fix the problem, digital tools, and involved people from across disciplines. When everybody is talented, everyone can get involved. No elite, no club, just an equal playing field.

"Designing is not a profession but an attitude”

I love the emphasis on attitude in the Bauhaus. Everybody can have an attitude, it’s a totally level playing field. It’s about lifestyle, it’s about seeing opportunities everywhere. Everyone should and can have the attitude to change and to design. And everybody can and should have the opportunity and attitude to be sustainable.

That means it is the designer with the right attitude who brings everything together.

The problems we have to solve now—and the problems we need to avoid in the future—are very complex and very diverse. They’ve been created because industries have been trapped in silos with no communication between them. So, for me, it’s the designer with attitude who can bring everything together—and we are all designers. We are bridge-makers, traversing industries, silos, technologies and mindsets to bring everything into a coherent and intelligible picture.

"The illiterate of the future will be the person ignorant of the use of the camera as well as the pen”

Remember László’s telephone pictures? Those pictures started a whole new discussion: What if, all of a sudden, a designer uses technology to create art? Is he still an artist?. Back then, photography was a new technology and László completely embraced it. But let’s not forget the pen which was, at some stage in history, a new, super smart piece of technology. The camera is to us now what the pen was for László. For us, the camera is a standard, familiar tool, like the pen. Perhaps new technologies like algorithms and artificial intelligence perhaps have a similar novelty for us that the camera had for László. The question is how we work together to use these tools. So, ladies and gentlemen, how do we do this?

Work. Go and travel. Go and talk with other people if you’re an architect or builder, in the loosest sense of those words. Or if you’re a writer, a musician, a content creator. Explore space, explore our oceans. Have you ever talked with a programmer, a software engineer or a data architect? I highly recommend it because a great piece of code can be as exciting as a novel and as impactful as a symphony. So, wherever you go, whatever you do, do something different. Talk with other people. Make things better, together.

Lisa Lang

Lisa Lang has gained recognition as one of Forbes Europe’s Top 50 Women in Tech, and has been listed as one of the 50 most important women for innovation & startups in the EU.She founded highly recognized companies like ElektroCouture, ThePowerHouse and FNDMT who are dedicated to push innovation within the creative and innovative industry eco systems. Lisa Lang is a direct adviser for creative industries, digitalisation and entrepreneurship for the European Commission on several high-level advisory boards, including Pact for Skills, Industrial Forum and the US/EU Trade & Technology Council.

Lisa Lang is on the advisory board to the Zurich university of arts as well as a policy advisor for Fashion Innovation Centre Sweden. She regularly teaches business and innovation strategies at the Porto Business School and has been given guest lectures at TEDx Athens, KryptoLabs Abu Dhabi and Oxford University.

Picture © VOGUE Greece

Riding the rapids of the great transformation

Charles Landry, inventor of Creative City concept and Co-Founder Creative Bureaucracy Festival, Berlin

Riding the rapids of the great transformation

The place to be

Periods of history involving mass transformation, like the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution or the technological revolution of the past fifty years are cultural shifts. They involve major adjustments in attitudes, ways of being and mindset. They can produce confusion yet also a sense of liberation and a mindshift combined with a feeling of being swept along by events. There were delights and dilemmas as they unfolded. Now, by contrast, the temper of the age, the Zeitgeist, is one of uncertainty, foreboding, vulnerability and lack of control over overweening global forces—especially our urgency to avert climate collapse or to avoid the polarising narratives that poison civilised conversation.

It is hard to see a way to a golden age, especially since we know we need to shift our economic order and a way of life that is materially expansive, socially divisive and environmentally hostile. And doing that cannot be grasped by a business-as-usual approach as it takes a while for new ethical stances and new ways of operating to take root and to establish a new and coherent world view.

Is there light at the end of the horizon in facing those challenges, even though some feel Europe is at the edge of exhaustion and without the energy or motivation to think, plan and act afresh and with vigour? Is that really so?

Will-o'-the-wisps?

Our crises, often dark and gloomy, weigh heavily and can push us into passivity and resignation. Yet crises can be opportunities and provide a gateway from one world to the next. Take a helicopter view of the vast range of initiatives happening, large and small, across Europe and beyond to address the solutions to create a more human- and nature-centred world and you see some positive patterns. Still, for the moment, fragmented and without sufficient power and traction, big agendas are coming together in unprecedented ways and driving this change are many: activists, civil society, politicians, researchers, inventors, artists, entrepreneurs, business, writers and more. There is a mood and a movement emerging. We are seeing the possibility of creating a different world driven on other principles. There is a Planet B in sight, even though to get there we must get Planet A right.

It is a compelling story. Think how eco-principles are beginning to shape our mindset and how that provides the frame and therefore

courage to move towards a green transition where the circular economy notion plays a crucial part. Think too how newer concepts like resilience help us work through the tasks ahead or how co-creation and the participatory imperative helps harness the collective imagination (since transformation is a collective endeavour). Think here too of the notion that the world is our commons. And not to forget a digitising world that allows, in particular, the cultural creative economy to run through systems like electricity in its inventiveness and with its immersive capacities. Sometimes the speed of the possibilities are dizzying and we always must be alert that we, rather than the technologies, are in control.

There is convergence and it is happening at escalating speed. From the beginning of the 21st century we finally saw a rapprochement between the two great ways of exploration, discovery and knowing: Art and Science. That rapprochement began to break down the widespread mutual incomprehension between the arts and sciences. The premise is that the most fruitful

developments in human thinking frequently take place at those points where different lines of creativity meet. By sharing their creativities, ways of knowing and the knowledge it enables, scientists and artists enrich and maximise each other’s potential and so encourage innovation. The transdisciplinary perspective is powerful when boundaries erode and as the methods of exploration and problem-solving can combine the linear, analytical and logical as well as the visual, kinaesthetic, spatial and musical. Allied to technologies that help shift ideas into reality, these synergies promote new forms of creativity which can result in ideas that can be turned successfully into products, services and solutions. This is the radical technological and cultural revolution underway. It has great opportunities. Together it is all transformative.

Incessantly, however, a bigger question remains ever-present and it needs to be answered: How do you make people feel viscerally that they must transform and change their minds—even while people realise that the world stands at the cusp of a crucial moment? Time is short in which to make the big difference towards one-planet living and we need to harness and share our collective talents, will, energy, intelligence and resources.

The year 2020 glitch

2020 was a year of radical reckoning. It was a time to think afresh. Did it make us finally listen and etch itself into our consciousness as we saw, momentarily, the skies clear and heard the birds sing again? This forced experiment of reducing carbon emissions gave us a glimpse of a possible other world. It reminded us that the world of ‘more and more’ cannot go on even though many still think of the old normal as our desirable and exotic destination. Crises like the pandemic provoke a dramatic reordering of priorities, deep reflection and rethinking and focused us—or at least should have—on what really matters: the common good and public interest. We saw too that, as Tom Burke put it, “civilisation is the thin film of order around the chaos of events.”

The pandemic was a wake-up call which triggered a dawning of humility as our collective hubris was humbled and old certainties crumbled. The pandemic created both clarity and confusion as in the eye of the storm it is difficult to see “where next” and how to get there. There seems to be no blueprint for how to move forward, yet we do have them.

We have an image of what could be: a zero-carbon society, a gender-equal society, a world where the dividends rather than the threats of diversity are promoted. The solutions are there but we think too often that technology will sort it out and that we can continue to just act as before. Technology takes on the responsibility and authority. We abnegate, we feel less answerable to what is happening. Shifting our mindset and how we think, plan and act—our behaviour—is the far bigger task.

Taking an eagle-eye view of the world in motion demands we unscramble the nested complexities and look at existing trends in order to assess their depth or superficiality, their characteristics and the nature of their impacts.

A good analogy is to think of change like an ocean. Ripples on the surface are less important than waves of increasing significance, which are themselves formed by tides, currents, climatic changes and

geological events which shape the movement and dynamics of the whole—and which might produce the occasional tsunami. It is that tsunami we need to avert.

We know the direction of travel if we do not act and it is the deep trends—think climate change—that we need to address. The challenge for all of us is to distinguish between the important, the less significant and the trivial: to understand the difference between a trend and a fad. And some trends are as persistent as they are predictable—just consider that when I was born the world population was about 2 ½ billion and when I die it will be more than 8 billion people. Not surprisingly, nature is suffering. Think water shortages, deforestation and animal extinctions. All are inextricably interwoven. In addition to this we are still operating largely with the same institutional structures made for a different age.

Variation of the mind

To make the rebirth—perhaps a Renaissance—a reality requires us to shift our mindset dramatically. That mindset should see things as an integrated whole. But this is not to downgrade the specialist—it is simply that we need to grasp the interconnections. Is it crisis, danger, the fear of impending doom, awareness, knowledge or is it a thoughtful, inclusive mind that shifts our thinking? This means understanding mindsets, mindflows and mindshifts. It implies reassessing how we think and learn, what we learn, the intelligences harnessed, the types of information used and disregarded. It demands new criteria to discriminate, judge and filter and a broader perspective which embodies a more inclusive sense of possible resources that are more free-flowing, lateral and creative. A changed mindset, rethought principles, new ways of understanding and generating ideas are the cornerstones of change.

A mindset is the order within which people structure their worlds and how they make choices, both practical and idealistic, based on values, philosophy, traditions, experience and aspirations. Mindset is our accustomed, convenient way of thinking and guide to decision-making. It not only determines how we act in our small local world, but also how we think and act on an ever-encompassing stage. Mindset is the settled summary of our prejudices and priorities and the rationalisations we give them. A changed mindset is a re-rationalisation of a person’s behaviour and is difficult as people like their behaviour to be coherent—at least to themselves.

Mindflow is the mind in operation. The mind is locked into certain patterns for good reason. To cope with the world we focus on the familiar, whether thought processes, attitudes, concepts and interpretations. The environment or context determines what is seen and what meaning is given. It operates below the level of conscious awareness. We cannot be completely open 24/7 although our default position must be a willingness to re-assess. Most of us will look at the world or a problem in a learnt way and have vested interests in perpetuating our current practices. An open focus can be seen as threatening, especially for discipline specialists as this might challenge the authority of their profession.

A mindshift is the process of dramatically reassessing core ideas. But how can you relax when there are pressures around you? Changing a mindset is unsettling and potentially frightening. Transformative effects happen in differing degrees: direct experience, seeing things work and fail and through conceptual knowledge. The most powerful means is the direct experience of having to change behaviour. This is where crisis comes in. By living through and understanding a crisis directly a person internalises learning and is able to repeat this learning in different contexts—it thus becomes replicable.

The challenge here Is that we travel with a weight of history attuned to bipolar thinking, operating in silos and are often sceptical of integrated, 360-degree perspectives and transdisciplinary thinking. Yet that cannot generate the solutions the future requires. The greater the number of perspectives applied to a problem, the more

imaginatively will it be approached. This is not to deny the value of our existing specialist knowledge. We cannot all simultaneously have the skills of an engineer, a biochemist or environmentalist, but we can understand their essence and so merge them with other skills or insights to make them more effective. This integration with other skills—especially in the human and social sciences, such as history, anthropology, sociology and psychology—has too often been lost in most affairs. For instance, a traffic issue is never only about cars and land use. If transport planners had understood psychology or culture better or the ideas of mental geography, they would have been more careful about building urban motorways that scorch their route through communities.

So, how can youthink small and with less when we are used to thinking big and with more? This transformation is a cultural project, the biggest of our times, as it is about values, mindset, attitudes and hearts, minds and skills. Seeing things culturally is powerful as culture is who we are. Creativity helps shape what we can become.

There are various ways to change behaviour and mindset: to coerce through force or regulation; to induce through payment or incentives; to convince through argument; to con, fool or trick people; to seduce (an odd combination of the voluntary and involuntary); and finally to create and publicise aspirational models. It is the latter we need to

focus on and it is not as straightforward as it sounds. It is likely to be a combination of all persuasive devices that takes into account immediate, short- and long-term impacts. At times the slowest way of changing a mindset can be by rational argument; yet while longer, it is the most effective, especially when evidence based.

This is where storytelling comes in and understanding the distinction between forms of communication—especially the narrative and iconic. Narrative communication is concerned with creating arguments; it takes time and promotes reflection and is linked to critical thinking; we build understanding piece by piece. Iconic communication by contrast seeks to ‘squash meaning’ and to crisply encapsulate an essence in order to create high impact and to show that what is being said feels significant. Our challenge is to embed narrative qualities and deeper, principled understandings within projects which have iconic power. This is where the talents embedded within the creative economy are so significant. They can create the messaging, the products, the experiences that are emblematic and which can leapfrog learning and avoid lengthy explanatory narratives through the force of their ideas, their projects and the symbolism they engender. The iconic project says it in one go and as you reflect, you understand what it is about.

How artists and those in the creative economy can help

What exactly is it about the process and act of singing, writing, dancing, acting, performing music, sculpting, painting, designing or drawing that is so special? Participating in these activities arguably harnesses the imaginary realm to a degree that other disciplines such as sports or much of science, which are more rule-bound and precise, do not. The latter tend to be ends in themselves, they do not change the way you perceive society; they tend to teach you something specific. This process of imagining has the benefit of forcing us to reflect, to develop original thought, to confront challenges and, crucially, to imagine that Planet B, which is where we need to get to. Nursing us through a green transition is a creative act where involvement with the arts can help.

Engagement with the creative activities combines both stretching oneself and focusing; feeling the senses and expressing emotion. Art, for instance, can broaden horizons and convey meaning with immediacy as well as depth; it can facilitate immediate and profound communication; symbolise complex ideas and emotions or encapsulate previously scattered thoughts; anchor identity and enhance communal bonds or, conversely, stun and shock for social, moral, or thought-provoking ends. Art can criticise or create joy, entertain, be beautiful and even soothe the soul and promote popular morale. More broadly, expression through the arts is a way of passing ideas and concepts on to later generations in a (somewhat) universal language.

What art does is not a linear process. Humans are largely driven by their sensory and emotional landscape in spite of centuries of developing scientific knowledge and logical, analytical, abstract and technical thought. We are not rational in a scientific sense, but we are a-rational rather than irrational. This is why all cultures develop arts.

What are the elements that help transformation along the way? We see here a combination of urgency, perhaps a crisis, and increasing evidence that the old ways do not work. Then a new concept comes in that encapsulates a way forward, as when the notion of sustainability emerged especially after the Club of Rome report in 1972. That in turn can drive an intent, a vision, a mission. Missions act as calls to action and as gathering devices to bring interests together towards a common aim. Crucially, we need real-life projects that embed the intent as it is only the lived experience of, say, a sustainability

initiative in action that makes an abstract concept real. Think here of the 15-minute city idea popularised by Paris and its focus on the city of proximity where walking, ease of access and most facilities are nearby and local. Here what might have seemed invisible becomes visible.

This reminds us that the new thinking needs to impact at three levels—the conceptual, the discipline-based and the implementational. It involves, additionally, reviewing the detailed mechanisms to make things happen, such as financial arrangements or planning codes to encourage and direct development into certain directions.

New thinking can generate a rebirth—a Renaissance. This Renaissance could unleash a process of re-enchantment that speaks to our deepest yearnings, our soul and our sense of wanting to become whole again where we and the world around us have the right balance.

Great placemaking is an art not a formula, but strong principles can help us along the way. For a long time I pondered, What are great places beyond their need to provide the means of survival and shelter and to be environmentally responsible? Five core themes came to mind: “places of anchorage and distinctiveness”, “places of connection and communication”, “places of opportunity and ambition”, “places of nurture and nourishment” and “places of inspiration and imagination”.

A place of anchorage and distinctiveness

This place feels like home. It generates a sense of the known, it is familiar and comforting, it feels safe and this is a place where I am sheltered and that creates a sense of belonging. It is distinctively itself. It celebrates where it comes from. It acknowledges its past, its heritage, its traditions and core assumptions about who it is. Its multiple identities, its ideas, its visions are etched into its way of life and this is what makes it special and unique. This place explains to itself where it comes from by its history, built fabric and urban design, its rituals, behaviours and activities. The routines of daily life and their predictability seem ordinary, but this ordinariness makes people feel rooted. Ironically, feeling at ease about itself gives this place confidence about where it is going and more relaxed about any changes that may unfold—so it dares to be innovative.

A place of connection and communication

This is a place of relationships, from the incidental to the casual to the deeply profound. You connect and communicate face to face with neighbours, work colleagues, friends, acquaintances and those different from you. You link to the wider world physically and digitally as well as with your past and potential futures.This place is locally bonded. It is at ease with itself and with the wider world. It reaches out. It is relaxed about meshing its diversities. There is seamless connectivity enabled by high quality urban design, good gathering places and possibilities for chance encounter. Its walkability and varied transport modes—internally- and externally-focused—connect beyond the city confines. Its digital infrastructures reach out to virtual worlds stretching out far and wide. It is the hub from which your transactions with the world flow—both those near to you and those afar.

A place of opportunity and ambition

This place fosters open-mindedness. It encourages a culture of curiosity, it provides choices, options and possibilities in our differing phases of life. It has a ‘can do’ attitude. There is an experimental culture and this keeps it flexible and adaptive to emerging circumstances and changes.Some places provide opportunities and others less so, yet this is a place in which to have ambition, ideals and aspiration. It sparks in you the desire to give free rein to your exploratory instinct and to open out. The raw materials of the city create the potential and are embodied in peoples’ creativity, skills and talents as well as its material resources. These are “things” like buildings and also symbols, activities and the repertoire of local products in crafts, manufacturing and services. They are our historical, industrial and artistic assets including architecture, urban landscapes and landmarks as well as our indigenous traditions of public life, festivals, rituals and stories, hobbies, enthusiasms and amateur cultural activities. This draws attention to the distinctive, unique and the special in any place. These resources are all potential opportunities. Acknowledging this can engender a spirit of generosity. It can create the desire to give back to your city. This helps generate civic pride, loyalty and trust.

A place of nurture and nourishment

In this place people can flourish and there are many opportunities to self-improve from the formal to the informal. This is a lifelong learning environment and a place where a culture of discussion is vibrant. This place cares about every aspect of your life. Here you can grow personally and professionally and the city helps you in this endeavour. It reinforces your necessary ladders of opportunity to move forward. It provides accessibility and enables mobility and helps move away constraints. It enables you to be more fulfilled and to widen your horizons. You are fed by these broadening perspectives and so learn and reflect. This can help citizens become more competent and confident and thus willing to participate in helping to shape, make and co-create their evolving city. To make this happen requires preconditions and these include good facilities, be they in education and research, health care, social provision, affordable housing, parks, good retailing and cultural facilities from the large-scale to the intimate. It will provide anything that makes it more liveable. Overriding everything there is a spirit of generosity and of giving back and this in turn inspires citizens to aspire to give of their better self and to become the best they can be.

A place of inspiration and imagination

This place has a visionary feel. It lifts you up from the day-to-day. You feel at one with yourself and your city. It provides a heightened level of experience by its beauty, and what that is remains ever debatable—and so it is also a place of possibility and excitement. It allows you to envision what could be. Here, aspiration and good intent is made visible in both the built fabric and through the vitality of its culture and urban programming. Each reinforces the other and this creates a virtuous spiral. This visionary dimension reflects the ideals and ethics that the city wishes to project to its citizens and to the wider world. These greater purposes beyond self-interest change over time.

In bringing about a New Renaissance, three foci are important. First, we need to heal the division between the city and nature in a changing climate; second, we need to be imaginative in working through how we live together with our differences; and third, we need to unleash the creative potential in each one of us.

Many in Europe understand this and they have the commitment and energy to make it happen. Europe is not exhausted – it is alive as never before!

Charles Landry

Charles Landry works with cities around the world to help them make the most of their potential. He is widely acclaimed as a speaker, author, innovator and he facilitates complex urban change projects.His aim is to connect the triad culture, creativity and city making. An international authority on using imagination in creating self-sustaining urban change Charles has advised cities or given talks in over 60 countries. He helps shift how we harness possibilities and resources in reinventing our cities and his Creative City concept has become a global movement. His book The Art of City Making was voted the 2nd best book on cities ever written by the planning website: http://www.planetizen.com/node/66462. His most recent books are The Civic City in a Nomadic World and The Creative Bureaucracy with Margie Caust. The latter has become a movement with an annual festival taking place in autumn every year in Berlin. The 2021 Festival had over 18000 visitors. Other books cover the measurement of urban creativity, the digitized city, urban fragility and risk, the sensory experience cities and interculturalism. For further information: www.charleslandry.com

Picture © Lukas & Joe

Intellectual Property and the Industry Commons

Industry Commons Foundation

Intellectual Property and the Industry Commons: Unlocking the Renaissance

Recognised as a major influence on economists, Leonard Reed’s 1958 essay ‚I, Pencil’ demonstrated that the invention of even the simplest of objects is the result of mass collaboration. A pencil is made by loggers, graphite miners and factory workers. Its form is predicated on the invention and widespread adoption of writing and drawing, and it requires an ecosystem of other technologies from pads of paper to marketing and distribution networks. The workers involved need to eat food and travel to work, and this all takes place within an elaborate economic and social web.

As interwoven, interdependent, cross-disciplinary and intricate as those systems were, Reed could not have foreseen the world to come. The extent to which the processes, raw materials and interconnected networks would become exponentially and globally more complex sixty or so years later would have been absolutely unthinkable. What had been the paradigm-shifting impact of Reed’s observation now needs to happen again at the next order of magnitude. We live in a context where the affordances of digital technologies, the entirely inescapable global supply chain networks and the ecosystemic challenges of the 21st century implicate and involve every single individual. We can no longer extricate ourselves from those global systems. Collaboration and the intersection of diverse ideas and specialisms are not merely beneficial for innovation in this context but fundamental for survival.

These intertwined framework conditions and cross-domain technological affordances lend themselves to the design of new supporting frameworks that are more inclusive and equitable. For the first time ever, the acceleration of industrial digitalisation provides an opportunity to build radical or disruptive innovation on top of existing intellectual property (IP), in a system that is fully trackable and accountable for all involved. Our tests conducted in the past five years2 demonstrate that ensuring traceability and attribution creates a powerful incentive to share data and other assets across fields, sectors and industries, helping humanity embrace innovation with greater motivation and efficacy than ever before.

Intellectual Property is a broad, complex and discursive area of study, subject to critique as a preventer of innovation and as a barrier to the creation of new ideas. Its fundamental condition as a category of property law has led to its status as a domain of guarded ownership, complicated routes to permission and a punitive legal minefield with steep costs for infringement – intentional or otherwise. The default position for access to industry IP has long been a blanket ‘no’ except under exceptional, usually expensive circumstances.

IP regulation has not followed the evolution of IP value creation.

In his ongoing quest to find out more about how people create and innovate, Professor Brian Uzzi, a professor of leadership at the Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University, and his team, measured the citations of every paper available in the Web Of Science, a repository of some 30 million scientific papers dating from the early 1900s to the present day.3 The articles with the most significant impact, he discovered, were collaborative. “Since 1950, teams have become more prevalent as a production mechanism,” he said in an interview for the BBC podcast Sideways.4 “Teams are getting bigger over time, [and] they are three to four times more likely to write a hit paper or produce a hit patent than individuals.”

He also noted that these teams were primarily composed of specialists from different disciplines: “Biologists working with economists and anthropologists, or historians working with big data experts and ethnographers.” This meeting of minds across boundaries is known as recombinant innovation, and it has an impressive track record of helping humanity make significant strides forward.

Fear of sharing IP, however, is deeply embedded. Sandra Vengadasalam of the Max Planck Digital Library describes how researchers feel about the issue: “If you ask them ‘What are you afraid of?’ – and it doesn’t matter which discipline – it’s ‘Oh, I’m super afraid to get scooped’.” In other words, there is strong concern that colleagues or competitors will steal a march on you and publish first. “It starts when you want to share your PowerPoint presentation, some pictures of your last microscopic data, whatever,” she continues. “There’s always the fear of ‘Okay, what can I give out? And what about my intellectual property?’”5

In the corporate world, the issue of IP is broad, complex, and carries significant responsibility for erecting barriers to ideas and holding back innovation. Indeed, amongst the closely guarded IP locked away by industry lies a substantial proportion of the estimated $100bn value of data sharing. But this isn’t simply an issue of trust. There can be problems relating to interoperability and conflicting standards, which make sharing difficult, despite the obvious benefits of overcoming them.