Our Ode to Creativity

Dr. Matthias Röder, Managing Director of Karajan Institute, Co-Founder of Sonophilia Foundation; Seda Röder Founder of Sonophilia Foundation, Salzburg

Our Ode to Creativity

In 2019, Michael Schuld of Deutsche Telekom asked whether an AI could be built to finish Beethoven’s 10th Symphony—a revolutionary homage and a birthday gift to Beethoven by the Bonn-based company bringing together technology, arts and communications. In this piece we reflect on the aspirational benefits of a “creative AI” and the reactions of recipients from different milieus. Although general audiences embrace the endeavour, cultural conservatives argue to exclude AI from entering the genius-oriented realm of creativity. Fear seems to be omnipresent, oblivious to the fact that Beethoven AI is a tool—like printing in the 15th century. In this short essay we make the case of how to put AI-supported Art to use for a human-centric Renaissance.

Picture above: Copyright Deutsche Telekom / Norbert Ittermann

Finishing Beethoven’s 10th Symphony with AI support would be monumentally complex—we knew right away. This is for two reasons. First, there exist only a very small number of sketches for the symphony and they are for the most part in a fragmentary state. Therefore, understanding Beethoven’s intentions for this 10th symphony is difficult. Second, honouring what Beethoven had already written, but keeping in mind his incredible versatility in working with musical material, required a very flexible and unique kind of AI that did not yet exist. As we started the project, however, a third complexity emerged to outtrump all others. Beethoven was seen as one of the pinnacles of human creativity and we were receiving criticism even before one tone was played: How could we even dare to create music with an AI that could compare with Beethoven’s music?

Two years later, in October 2021, Beethoven X – The AI Project was premiered, at Deutsche Telekom’s headquarters in Bonn. Thousands of people around the world followed the live stream along with hundreds in the audience. Not one person in the crowd was able to tell where exactly the sketches of Beethoven ended and where the music of the AI took over. Standing ovations filled the hall for many minutes… Music aficionados, technology enthusiasts and distinguished media outlets such as CNN, BBC, BILD and many more from around the globe seemed to love the result, while the album entered the German pop charts.

Nonetheless, following the premiere, a heated discussion broke out.The conservative feuilletonists and hardcore traditionalists labeled Beethoven X as “sacrilege” and were particularly bitter in their judgement. Going over the music motif by motif, they discussed whether our AI matched Beethoven’s “genius” music, or whether it was just an unemotional imitation of the original—often confusing and criticising the original fragments with music produced by the AI. The discussion however showed striking similarities to the criticism that others have received for creating their completion of Beethoven’s 10th symphony. That’s when we realised that the whole debate was clearly not about the music itself nor about the capabilities of the technology—it was about excluding AI (and sometimes even humans) from entering the genius-oriented realm of creativity.

But Beethoven X heralds a future where there are no barriers of entry into the ivory tower of arts. It foreshadows a new kind of Renaissance that is all about democratising creativity for all rather than making it a privilege for a few. Most importantly, Beethoven X aspires to be part of a future where humans and machines interact productively so that more people can harness the benefits of technological tools to unleash creativity, to self-actualise and to contribute to humanity. Technologies are advancing rapidly. Therefore, unleashing their potential for the greater good is, quite frankly, a pressing matter. We should, perhaps, be maximising the creative potential in the world with much more urgency. Consider this: according to the numbers compiled by the Austrian Statistics Agency, only 0.02% of the entire world population is working in any innovation and creativity-related field—R&D, environment, food, societal innovation, arts… you name it!

But can it truly be that only one in 5,000 people are actually creative? Can it truly be that only one in 5,000 people can contribute to innovation or to arts? Of course not!

We live in a world obsessed with not wasting resources, yet when it comes to human potential, we seem somewhat complacent. Considering our world’s current situation, we need all the help we can get to start asking different kinds of questions and exploring new pathways where old ones are failing. That is precisely where the power of human-machine interaction lies.

Our Beethoven AI gave us options, options we could never have produced without it in such a timeframe. In so doing, it maximised our creativity. The options it so effortlessly produced were threefold. First, they expanded our horizons in that AI didn’t care about our conventions, taboos, or rules. Second, they gave us freedom, putting us in the driver’s seat with an amazing array of choices.

Finally, they saved us tons of time which we could spend focusing on and learning about things that really matter. All of that is indeed “human” music to our ears.

If an AI can help humans be more creative—more “human” even—the question remains: Why are we not employing this technology much more widely to address and solve other problems too?Perhaps the answer is that our age lacks courage. Business-as-usual mentality and fearing failure is omnipresent in our organisations. Many are reluctant to experiment with AI within the context of creativity. Or maybe the fear lies in the idea of a machine becoming a “more creative individual” than us, as if we were in competition.

Humans are not computers, nor should they be treated as such. Unfortunately, this is still the case: just look at your child’s homework sheet, and you’ll immediately know what we’re talking about. Our systems should be focusing more on raising first-class creative and collaborative thinkers, learners and inventors, rather than programming what are essentially second-class calculators.

Picture left: Copyright Deutsche Telekom / Norbert Ittermann

Let’s accept the reality: Humans are generally not very good at reproducing Knowledge 101. Our memory capabilities and speed of data-processing are simply flawed in comparison with machines. But we excel at other things, particularly at empathy and creativity. We are also extremely good at unleashing the potential of all sorts of tools around us: We invent tools to improve the lives of people we’ve never even met. We utilise tools all the time to inspire and connect with each other. Our Beethoven AI is one of them.

This is a turning point in history. Instead of asking whether someone is “allowed” to use AI in the creative process or to emulate the style

of a creative superstar, we should be instilling the right mindset and the joy of experimentation to awaken the creative superstar inherent in everyone. It is high time we stop putting people into boxes only to later instruct them to think outside of the box!

As the debates and reflections around our Beethoven experiment unfold, we must begin acting on that promise.

Our world is slowly coming out of the Industrial Age, but what’s next is not the age of technology, digitalisation, or transhumanism.

It’s the Age of Creativity!

Matthias Röder

Dr. Matthias Röder is an award-winning music and technology strategist. He is Co-Founder and Managing Partner at The Mindshift, a consultancy on creative leadership and innovation strategy. Matthias currently serves as a board member of the Karajan Foundation and is the Managing Director of the Eliette and Herbert von Karajan Institute. He is also a member of the board of trustees of the Mozarteum Foundation. In 2017, Matthias founded the Karajan Music Tech Conference, a cross-industry event to promote breakthrough technologies in music, media and audio. He is also the founder of the Classical Music Hack Day series which he launched in 2013. Together with his wife, Seda Röder, Matthias co-founded the Sonophilia Foundation, a non-profit that promotes a scientific approach to creativity. Matthias has won numerous prizes and accolades for his work, including most recently, the “Game Changer” Award of the Chamber of Commerce Salzburg. He is a sought-after speaker and lecturer who has taught at Harvard University, the Change & Innovation Management Program at University of St. Gall, and Salzburg University. He holds a PhD in music from Harvard University and is an alumnus of the Mozarteum University Salzburg.

Picture © HUBERT AUER Salzburg

Seda Röder

Seda Röder, aka “the piano hacker”, is an author, entrepreneur and philanthropist devoted to cultivating creativity in society and organisations. She is a sought-after speaker, consultant to DAX listed companies and the founder of the Sonophilia Foundation; a non-profit organization dedicated to advancing the scientific research of creativity and critical thinking. Seda is Co-Founder and Managing Partner at The Mindshift, a consultancy on creative technologies and change leadership. Furthermore, Seda is a fellow and a member of the Salzburg Global Seminar Corporate Governance Forum, angel investor and network partner at the European startup accelerator Silicon Castles. In 2018 Seda received the Game Changer Award at the Austrian Chamber of Commerce for her business merits. Before relocating to Europe, Seda taught music performance, theory and history at Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) as an Associate and Affiliated Artist.

Picture © Private Collection

New worlds emerge from old sounds

Artist, Music producer, Label owner and Co-Founder of Electronica & Techno label Kompakt, Cologne

New worlds emerge from old sounds: What we can learn from music about making new worlds when Man and Machine meet in new ways?

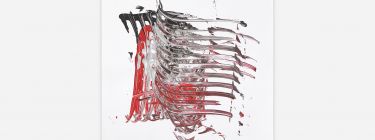

My work RÜCKVERZAUBERUNG 4 is an ambient trip of one hour through more than three centuries of musical history—and more. It resembles the Renaissance principle of constructing new worlds—in this case in music—with new scientific methods building on historical inspirations. Aligning Man and Machine in radically fresh, innovative ways is a method to create and make the new. My interpretation of this Renaissance method, applied in the 21st century, is “Looping”—in music and painting.

We hear the medieval sounds of lutes and flutes weaving into fragments of baroque falsetto singing, bells and bugles, creating abstract, amorphous sound constructs. Little spinet and harp loops gyrate intoxicatedly across beautifully feverish violin planes. Atonality and euphony flow into each other effortlessly and part again. New worlds emerge from old sounds.

In my musical and pictorial work I have mostly followed strictly conceptual principles, which I repeatedly refine and variegate. Besides a predominantly sample-based, sometimes abstract, sometimes gestural, sometimes figurative musical language, it is mainly the loop principle that has fascinated me all along. The static or varied replay of minimalistic, repetitive structures births certain patterns and shapes. This way of creating is influenced and structured by computer-based programs. And although, or maybe because of, the computer being my primary artistic medium in both disciplines—and I mainly considers myself a digital artist—I occasionally transpose my conceptual, mostly serial ideas to the „live“ instrument (Freiland Klaviermusik) and „real“ colour (machine painting).

My work since 1990 can be understood in light of one of today’s most pressing questions: How are Man and Machine related? My work has been driven by the rapid development of Artificial Intelligence which is constantly changing our understanding of this relationship. The traditional balance of Man and Machine, of Artificial and Artistic Intelligence, formerly carved out in the Renaissance, is being changed in the 21st century by new emerging technologies. RÜCKVERZAUBERUNG 4 is an exploration of this change expressed in the musical and visual arts: The Loop as a Method.

About the work of Wofgang Voigt:

The creative body of Wolfgang Voigt has always been characterised by complexity, boundlessness, unpredictability. The negation of the bounds of genre, style, and taste has been and still is today a crucial element of his body of work, just like the uptake, quotation and processing of external contents through universal sampling. Having been socialised in the pop culture of the 1970s and 80s, Voigt has since been creating his very own art-music cosmos influenced by glam rock and jazz, new wave and folk music, pop art, and digital expressionism. In the 1990s, Voigt, a founding member and influential part of the Cologne-based electronic label Kompakt, advanced in the wake of the globally booming techno movement, restlessly driven by his iconic straight bass drum, producing countless projects ranging from formally rigorous minimalism and expressive hardcore acid, to gabber and polka, to driving the conceptual techno made in Cologne (Sound of Cologne). His audiovisual project GAS, based on psychedelically-compressed classical sound sources in combination with ecstatically-focused forest photographs and films, has captured audiences far beyond electronic music and techno.

Listen to & Buy WOLFGANG VOIGT – RÜCKVERZAUBERUNG 4 10/2011 Profan CD11: https://kompakt.fm/releases/rueckverzauberung_4_digital_album

Wolfgang Voigt

Grown up and socialized in the pop sub-culture of the 1970s and 1980s, Voigt has developed his own art and sound that cross genres, mixing music styles such as glam rock, pop, jazz, classic, punk, and new wave, and art movements such as pop art and the Neue Wilde (the ‘New Wild Ones’). Inspired by the minimalist structures of this creative expressions, Voigt works around the most diverse facets of his own ideas of subversive concept art and music. Two fundamental approaches, through innumerable variations, characterize Voigt’s music and artwork. The first: the loop principle – the static or varying repetition of minimalist, repetitive structures which generate specific patterns. The structure of computer-based music production and associated software clearly and strongly influences this artistic concept, reflected in Voigt’s body of art and music. The second: the abstract deforming and condensing of external resources, i.e. the sampling of different sounds or images reduced to their original basic structure, their raw aesthetics, in a certain sense their (hypothetical) liberation, and transferred into a new context – a process that Voigt calls „Entdeutung“, i.e. de-signification.

Picture: © Unland