A millenary contemporaneity

Prof. Dr. Christian Greco, Director of Museo Egizio; Luca Dal Pozzolo, Director of Cultural Observatory of Piedmont at Fitzcarraldo Foundation, Turin

A millenary contemporaneity

The Egyptian Museum of Turin as a role model for societal dialogue and design of a desirable future

Archaeological museums have a great potential to express in the contemporary world, in showing how ancient societies have reacted to the challenges of sustainability and of their relationship with the climate, and how they have constructed cultural identities within an immense range of alternative ways of life and modes of thinking. To build an explicit relationship between antiquity and the criticality of the present is the wider task of the Next Renaissance now visible in many civic initiatives, scattered innovations and seemingly unrelated instances. This piece explains how this full vision is assumed by the Egyptian Museum and how it enriches with its cultural contribution of historical heritage the conceptual alternatives for the society at large in the design of a desirable future.

Heritages´ role for the future in crisis

As has been pointed out by anthropologists and sociologists, the present time has taken on an inflationary dimension which tends to overlap with the past and extends into the future, depriving it of its novelty and possible change: a formless and intrusive aorist that hinders the perception of the depth of history and the possibility/need for a different future. In this context, history has lost its role as the privileged key to interpreting society but, at the same time, the pandemic has highlighted the extreme fragility and uncertainty of a present that is anything but stable and predictable, furrowed by sudden fractures that open up disturbing trajectories. Moreover, a sneaking feeling of nostalgia for the pre-pandemic period and a recall to a presumed previous normality are all signs of how difficult it is to look straight at the heart of the current critical situation and imagine a possible new design for the future.In this condition, the crisis that has profoundly affected museums and cultural heritage as a result of the lockdowns runs the risk of being read from a reductive economic point of view, as the loss of an entertainment offer, the downsizing of a decisive asset of tourism, the economic damage by the suspension of activities.

Although all this is highly critical for the economic sustainability of museums, it is necessary to focus on the contribution and the cultural mission that museums and cultural heritage are able to offer in order to emerge from a crisis that shakes the 20th-century roots of our European societies.

On the other hand, at the international level, the idea that museums are theatres of memory where local and global identities are defined, and where different visions of the past and present meet the future, is now shared. This is precisely one of the central nodes to nurture a new impetus to address the current challenges to their complexity, and museums, libraries and cultural heritage are the privileged places to inhabit, share and structure the crossroads between multiple identities, new constructions of citizenship and paradigms for social, economic and cultural sustainability.The need to recover the perception of the depth of time and of a future that is to be built through the choice of alternatives is today one of the great challenges that museums and cultural heritage can help to address, provided they are radically transformed: overcoming the concept according to which artefacts are exhibited and separated from their historical context, showing them as objects of particular beauty. Isolating them from their original context does not allow us to interpret an era.

All this implies an epochal passage from a logic of relationship with the public centred on the exhibition, to a dimension of producers of content, both for the public in presence and for the public at a distance as the pandemic has shown.

Although there’s no better way to enjoy heritage than in person, not even with the most sophisticated digital technologies available, museums and cultural heritage can no longer be understood primarily as physical containers to be filled with tickets, but as cultural publishers, capable of graduating their reach and disseminating cultural products on all possible supports towards the public in presence, the distant public, schools, universities, civil society, sewing up the past with the dimension of the future.

Innovating the futures´ context for heritage: The Egyptian Museum's commitment

At this decisive point in time, the wider aim is to perceive museums as laboratories of innovation, fundamental for the harmonious development of society, and as reference institutions for the construction of contemporary knowledge that must now face new challenges. Only in this way will we truly give voice to what Article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, approved on December 10, 1948 by the General Assembly of the United Nations, clearly reminds us. Research, scientific and technical innovation, heritage and society are inextricably linked, and from this relationship must spring the collective rebirth that, starting from solid cultural roots, is able to direct the path to a sustainable future.

The Egyptian Museum of Turin is leading in such innovations of the narrative of its contents and experimenting with new ways of relating to its public. Below is a brief description of some of the research guidelines inspired by the approach described above and the related actions that characterise the daily work of the museum.

The alliance between science and archaeology

The places that preserve the vestiges of the past can function as laboratories of innovation, experimenting with new techniques of investigation, through which it is possible to ‚interrogate‘ the objects in different ways. In this field, a real dialogue between humanists and scientists can produce truly innovative results, combining the potential offered by modern science with the questions suggested by objects but still unanswered. The time has come to introduce what we could call a digital humanism in which archaeologists, anthropologists, architects, historians, philosophers, neuroscientists, and psychologists work side by side with chemists, physicists, and computer experts to arrive at the definition of a new semantics that allows us to understand and process the complexity of reality. Starting from, for example, the exhibition Invisible Archaeology, the Egyptian Museum offers the heritage of questions, acquisitions, hypotheses and problems to be faced and explained to different audiences. The alliance with science for the reconstruction of the complexity of life and everyday life does not only imply a low invasiveness of the investigation and delicacy in the impact on the finds (a factor of absolute importance) but also the sharing of the knowledge and awareness of the public distant eras.

Science and the sacredness of life

The scientific investigation does not only concern objects and findings of material culture, but puts at the centre of its diagnostics life itself through the investigation of mummies and human remains that represent deposits of valuable information on lifestyles, diseases, genetic makeup, and so on. For the Egyptian Museum it is necessary that these investigations and analyses be returned to the public as a positive approach against the objective risk that every exhibition and every museum runs: the evocation of the gaze of the Gorgon that petrifies every object on which it rests. Fighting the dehumanisation of the mortal remains of life, degraded to crystallised relics, no longer worthy of the pietas that was among the reasons for their coming into our presence, is an ethical commitment assumed by the Museum, starting with the debate on the appropriate way to display human remains. Explaining how scientific and genetic investigations with similar methods can be applied today—not only to lives extinguished thousands of years ago but also to the recent deaths of migrants at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea in order to give them back their names and identities—opens novel societal questions, rooted in the distant past and facing our future and that of our children.

The Egyptian museum as part of a living geography

An archaeological museum dedicated to Egypt runs the risk of being placed in a subsidiary temporal sequence—before the Greeks—but in an ancient geography, no longer related to contemporaneity. Precisely to prevent this possible interpretation, the policy of recent years has focused—also with promotional and marketing initiatives—on the relationship between the museum and Egyptian, Arabic-speaking and African communities in Italy and Europe, to allow opportunities for cultural recognition and pride, for in-depth studies of history and for comparison between places of origin and residence. Egypt is not only a region of history, or a place of excavation and scientific cooperation with which the Museum shares intense exchanges, but one of the most influential countries in the geopolitics of the Mediterranean and an inevitable point of reference for thousands of new citizens. An effective reception policy and the construction of an intercultural society are also based on the recognition of the cultural values of others, on their valorisation, on the possibility that cultural heritages can be reciprocally known and shared, negotiated in their implications and underlying values, and not used to build oppositional, exclusionary identity exoskeletons based on the denial of the other.

The contemporaneity of the past.

The commitment to proposing innovative trajectories, in extreme synthesis, is aimed at making evident to the different audiences—with every, narrative, literary and technological instrument available—how archaeology, probing ancient time, contributes to questions about and redefines the present. This is a necessity as well as a challenge to museums if they opt to be a driver for the Next Renaissance Europe: How can museums represent a field of non-partisan cultural confrontation on the great themes that from antiquity to today existentially invest the human race? The most recent one is the overwhelming transformative power of our societies, which puts at risk the sustainability, not of the planet but of the human species in its development trajectories. The Egyptian Museum hopes to be an inspiration and living lab for museums across the globe, extending here and now an invitation to collaborate and co-create the future of museums for the future of a resilient society. In fact, the scientific investigation in archaeology is one of the most interesting frontiers in the challenges of contemporaneity.

Luca dal Pozzolo

Luca Dal Pozzolo, 1956, Architect, co-funder and responsible for Research of Fitzcarraldo Foundation. From 1998 is Director of Piedmont Cultural Observatory and member of the Scientific Committee of CCW, Cultural Welfare Centre and Member of the cultural Commission of the European Institute of Design (IED). He teaches in Bologna Economic Faculty, (Regional Cultural Policies), in Politecnico di Torino (master in museography) and in Lugano, Master in Advanced Studies in Cultural Management.He designed many museum’s exhibitions and cultural institutions and published many articles and books on cultural economics, museums and Heritage, (Esercizi di sguardo, 2019, Il patrimonio culturale tra memoria, lockdown e futuro, 2021), and is directing the book series Geografie Culturali, for the Italian publisher publisher Editrice Bibliografica.

Picture © Fondazione Fitzcarraldo

Christian Greco

Born in Arzignano (VI) in 1975, Christian Greco has been Director of the Museo Egizio since 2014. He managed a refurbishment of the museum building and a renovation of its galleries, completed on March 31st 2015, whereby the Museo Egizio was transformed from an antiquities museum into an archaeological museum. Trained mainly in the Netherlands, he is an Egyptologist with vast experience working in museums. He curated many exhibition and curatorial projects in the Netherlands (Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden; Kunsthal, Rotterdam; Teylers Museum, Haarlem), Japan (Okinawa, Fukushima, Takasaki and Okayama museums), Finland (Vapriikki Museum, Tampere), Spain (La Caixa Foundation) and Scotland (National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh).While at the head of the Museo Egizio, he has set up important international collaborations with museums, universities and research institutes all across the world. Christian Greco is currently teaching courses in the material culture of ancient Egypt and museology at the University of Turin and Pavia, and he is Visiting Professor at the New York University in Abu Dhabi. Fieldwork is particularly prominent in Greco’s curriculum. For several years, he was a member of the Epigraphic Survey of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago in Luxor. Since 2011 he has been co-director of the Italian-Dutch archeological mission at Saqqara. Greco’s published record includes many scholarly essays and writings for the non-specialist public in several languages. He has also been a keynote speaker at a number of Egyptology and museology international conferences.

From the Station of Being to Societal Transformation – How design can drive a new European Renaissance

Ambra Trotto, PhD; Prof. Caroline Hummels; Jeroen Peeters, PhD; Daisy Yoo, PhD; Professor Pierre Lévy Eindhoven University of Technology, National Conservatory of Arts and Crafts

The design and how it came to be

The ‘Station of Being’ is a fully functional, experienceable prototype of a Smart Bus Station in the Northern Swedish city of Umeå that was opened in 2019. The project was initiated by the City of Umeå and partly funded by the H2020 Smart City Lighthouse project RUGGEDISED.

The aim of this design is to make public transport more attractive, to promote an increase in use and, in turn, to lower the carbon emissions of the city. The Station achieves this by affording a positive waiting experience, aiming to turn wai(s)ting time into time to feel, reflect, pause and move: in a nutshell, to be.

Two main components of the design contribute to the passenger’s experience.

– A dynamic light and soundscape informs passengers in or near the station which bus is about to arrive. A subtle play of lights refers to the arriving bus line through its colours, while a soundscape plays to tell stories about the character and history of the line’s final destination. This combination offers ambient information which can be perceived on one’s sensorial periphery, removing the need for passengers to pay constant attention to the coming and going of busses.

– Wooden ‘pods’ hanging from the ceiling provide a physically comfortable place for waiting passengers and contribute to a feeling of safety. The pods can be turned 360 degrees, providing a way to lean and stay out of the wind or just mindlessly sway. The pods allow one to seclude oneself, or to create a social space.

Picture above: Station of Being, Copyright by Samuel Pettersson

The design and development process for the Station of Being followed the Designing for Transforming Practices approach (Hummels, 2021, Trotto et al. 2021), which catalyses liveable ecosystems by transforming existing practices into truly sustainable ones through design. It does so by initiating and curating multidimensional synergies, driven by beauty, diversity and meaning. The scope is to imagine and propose sustainable futures, in which all beings are respected and actions to heal the planet are taken, thus moving towards a horizon of collective thriving. Those futures are populated by people living purposeful lives, in beautiful living spaces.

The design process of the bus station involved a large number and a wide range of stakeholders. The project was driven by the national Swedish research institute RISE in collaboration with a design and engineering consultancy, Rombout Frieling Lab. The project was owned by the Comprehensive Planning Department of the City of Umeå and the Streets and Parks Department acted as a client. The process further involved the Umeå Institute of Design at Umeå University, the public transport company Ultra, the local energy company, Umeå Energi, real estate developers, maintenance workers and engineering and building companies.

Elucidating transformations

Transformation is a substantial change, often associated with innovative and radical change. Transformation occurs when one configuration is converted or changed into another, whereby the change is major or complete (Mirriam Webster Dictionary). We use the term ‘transformation’ when designing for transforming practices (TP) to denote substantial enduring change of values, ethics, and related behaviours of a person, a community or society, triggered by the need of creating alternative ways to engage with the world, addressing specific societal challenges. In this context, people and communities become (and are) transformation itself. This demands a leap, a paradigm shift, even for what seems to be smaller personal transformations (Hummels et al., 2019; Hummels, 2021, Trotto et al. 2021).

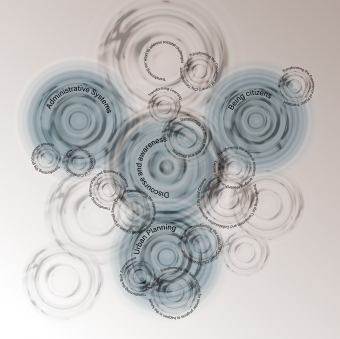

Picture right: Copyright by Ambra Trotto, Caroline Hummels, Jeroen Peeters, Daisy Yoo and Pierre Lèvy

The process that led to the development of the Station of Being spans from the inception of a procurement process in 2017 for its construction to today being a functioning bus station in Umeå. This project triggered different levels of societal transformation grouped around four types of practices, as shown in the figure below. We saw transformations emerging in administrative practices related to the organisational and legal activities and procedures of all parties involved. Moreover, the Station of Being has brought about several transformations in the way one can be an active and engaged citizen, and in the way one can be a responsive municipality and community,

particularly in the domain of urban planning. Finally, it has changed the overarching discourse on how to research, develop and transform smart cities and communities.

Some of these transformations were explicitly intended, some of them emerged unexpectedly along the way and had an impact on the process, and some are indirect consequences of the process that we observed over time. We will elucidate these four practices, by unpacking one illustrative example each, regarding transformations at different levels and scales of the process.

Administrative systems: Transforming the Contract of Collaboration

The procurement was won by a consortium consisting of RISE in collaboration with Rombout Frieling Lab. Following a standard public works building contract, a dense, standardised framework of environmental impact, safety, working environment and other regulations and legal responsibilities were included in the contract. RISE could have developed and proposed a solid and participatory process; however, it was not RISE’s role to be responsible for the building process, neither administratively nor technically. Yet the City could not leave these responsibilities out of the contract. In the end, an agreement was made about which specific responsibilities could be removed from the contract, with the agreement that they would pass on to the builder to be contracted in the future. Working on such innovative projects surfaced the need to change the content as well as the intent of contracts. The project demonstrated an administrative and relational transformation that required mutual trust.

Urban planning: Transforming the notion of “smart cities” development

The original brief included a number of practical and functional requirements, and stated amongst other things that the bus station should: (a) be highly innovative, smart and sustainable; (b) promote a feeling of safety for passengers; and (c) involve citizens in its development. Most importantly, however, special emphasis was placed on the requirement to prevent heat loss from buses when opening their doors to (un)boarding passengers. This is a typical example of a narrowly-defined, reductionist approach to requirements, which can lead to inadequate, mediocre solutions. It was clear to the design researchers that a reframing of the project and requirements was necessary in order to approach the challenge as a ‚wicked problem‘ and come up with innovative interventions.

The first step in this reframing process was taken through a course at the Umeå Institute of Design. About 20 design students carried out design interventions in the city,

looking for meaningful experiences of public mobility. They involved passengers and bus drivers in designing and testing prototypes and mockups. At the same time, the team of designer-researchers found that an indoor bus station was not a viable option. The research showed that such a solution would not reduce carbon emissions, but rather it could lead to a potentially unsafe and difficult-to-maintain facility. The portfolio of design ideas from the students and the design research team pointed in another direction for reducing carbon emissions, namely increasing the willingness of people to use public transport more, by offering a pleasant traveling experience for passengers. Accordingly, the brief and the expectations of the municipality were transformed throughout the design process.

Being citizens: Transforming the Experience of Public Transport

Opened in October 2019—shortly before the pandemic hit—the Station of Being saw an increase of about 40% of passengers in the months following its opening compared to the previous year. Furthermore, the increase doubled compared to other nearby stations. A small pilot field study showed that people generally have positive feelings about the new station, and that the design scored highly with women in particular, due to the sense of safety it evokes (Åström, 2020). The Station of Being is now included in the Umeå Gendered Landscape (n.d.), and is deemed to have positively transformed the waiting experience.

Discourse and Awareness: Transforming learning

The final transformation we highlight here has to do with lifelong learning. The design research team initiated a participatory process aimed at empowering the relevant stakeholders, especially the municipal staff. Their active involvement in the design process increased their confidence in working beyond the beaten track. It reassured them in their leadership capacities and in their ability to participate in transformative processes. A clear example concerns the municipality’s snow ploughing service. Umeå is a town in northern Sweden that experiences heavy snowfall during several months of the year. The service was initially sceptical about how the design team might consider their needs. However, during the process they were able to regularly test how the bus station could be easily cleared of snow using machines, rather than the existing manual methods at traditional bus stops. The process increased their motivation, commitment and enthusiasm.

Design for Transforming Practices for a new European Renaissance

We are facing major societal challenges that call for multifaceted transformations, as illustrated by the example of Station of Being, including political, economical, social, technological, legal and environmental factors (also indicated as PESTLE) as well as demographic, ethical, ecological, intercultural, organisational and digitalisation factors (e.g. labeled as STEEPLED, DESTEP and SLEPIT) (Helmold & Samara, 2019). The escalation of tensions in our connected society—and the rebellion of the planet that has been exploited without any respect for its balance and the rights of all those inhabiting it—urgently demand new ways of working, fuelled by alternative value systems that are different from the status quo. These new ways of working together and inhabiting a planet in need of healing require transformations toward practices of mutual care, of repairing, experimenting, making and unmaking together. The Station of Being exemplifies some of these transformations.

The approach that we use in projects such as RUGGEDISED is known as Designing for Transforming Practices, in short TP (Hummels et al. 2019). It is an approach, or rather a quest to engage with the world in co-responsible ways, by transforming the status quo and developing new alternative practices (Hummels, 2021). TP catalyses liveable ecosystems by “transforming existing practices into truly sustainable ones, through design. It does it by initiating and curating multidimensional synergies, driven by beauty, diversity and meaning. The scope is to imagine and propose sustainable futures, which are those futures where all beings are respected and actions to heal the planet are taken, towards a horizon of collective thriving. Those futures are populated by people living purposeful lives, in beautiful living spaces” (Trotto et al. 2021).

This approach is founded on five principles: complexity, situatedness, aesthetics, co-response-ability and co-development. TP is not about ‘solving’ the problems, but about ‘dissolving’ them by using design to explore and imagine futures and concretising them in the here and now to experience the alternatives. TP stimulates critique, elicits dialogic debates that arise from tensions between the status quo and

alternatives, and finds new avenues for the flourishing of a new civilisation. Only from new practices can a new civilisation, and hence a new renaissance, arise (Trotto, 2011).

The process of the Station of Being underlines the ability and competence of designers to deal with ‘wicked’ problems, i.e. messy, complex problems which cannot be tamed or solved (Rittel & Webber, 1973). Designers have the attitude, skills as well as methods to deal with complexity and to tackle complex problems pragmatically. The quality of design and designers is that they can reframe and reconfigure challenges with the aim to dissolve them in the long run. With TP, we do not only aim at dissolving wicked problems, but we also focus on impacting future trajectories by changing attitudes and practices of involved parties, breaking boundaries between silos and addressing organisational aspects, as shown in the Station of Being.

Not only are they highly complex, but also our societal challenges carry a strong sense of urgency, asking for immediate actions. Hence we are bound to take actions

in the here and now while simultaneously generating a long-term outlook for both the future and history (100 years and more), thus connecting past, present and future. By working on several time scales at the same time, we prepare ourselves for serendipity, emerging outcomes and wicked impact. Above all, we do so by engaging with a broad spectrum of stakeholders to evoke co-response-ability.

With TP we want to contribute to a European Renaissance. In this new era, we are inspired and empowered to collaboratively explore processes and practices founded on care, trust and repairing. To be

able to contribute even better to a European Renaissance, we have recently made an exciting new step in our quest and established the Design Competence and Experience Centre, which “exists to catalyse ecosystems and transform existing practices into more sustainable ones, by initiating and curating multidimensional synergies, with beauty, diversity and meaning, for sustainable futures” (Trotto et al, 2021). It is an endeavour in which creativity can lead the ways (as opposed to “the way”) to unlock ourselves from old paradigms that lead to the depletion of the planet and of humankind. We invite you to join the quest for ushering in a European Renaissance.

REFERENCES

Åström, M. (2020). Innovations in Urban Planning: A study of an innovation project in Umeå municipality (Dissertation). Retrieved December 02, 2021, from http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-171983Helmod, M. (2019). Tools in PM. In: M. Helmold and W. Samara (Eds). Progress in Performance Management: Industry Insights and Case Studies on Principles, Application Tools, and Practice, Springer. p 111-122. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20534-8_8

Hummels, C. C. M., Trotto, A., Peeters, J. P. A., Levy, P., Alves Lino, J., & Klooster, S. (2019). Design research and innovation framework for transformative practices. In Strategy for change (pp. 52-76). Glasgow Caledonian University.

Hummels, C. (2021). Economy as a transforming practice: design theory and practice for redesigning our economies to support alternative futures. In: Kees Klomp and Shinta Oosterwaal (Eds). Thrive: fundamentals for a new economy. Amsterdam: Business Contact, 96-121.

Rittel, H. W., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy sciences, 4(2), 155-169. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01405730

Trotto, A., Hummels, C. C. M., Levy, P. D., Peeters, J. P. A., van der Veen, R., Yoo, D., Johansson, M., Johansson, M., Smith, M. L., & van der Zwan, S. (2021). Designing for Transforming Practices: Maps and Journeys. Internal publication. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven.

Umeå Gendered Landscape (n.d.). About the gendered landscape. Retrieved December 02, 2021, from https://genderedlandscape.umea.se/in-english/.

Ambra Trotto

Ambra is the Design and Research Director of the European Design Competence and Experience Center for inclusive innovation and socetial transformation and associate professor at the Umeå Institute of Design.She leads the Digital Ethics initiative at RISE, directing the strategic work regarding how RISE supports societal actors in taking ethics into account, when designing transformation with technology as a material. She is part of the RISE Development Team of the strategic research area Value-shaping System Design. She has initiated the environment of RISE in Umeå, leading The Pink Initiative, which is establishing, through design research, local, national and international multidisciplinary ecosystems, supporting business and society to thrive and create sustainable futures. Ambra has 16 years experience in writing and participating in various forms of European projects. Ambra Trotto’s fascinations lie in how to empower ethics, through design, using digital and non-digital technologies as materials. Strongly believing in the power of Design and Making, Ambra works with makers, builders, craftsmen, dancers and designers to shape societal transformation. Within her design research activity, she produces co-design methods to boost transdisciplinary design conversations. She closely collaborates with the Research group of Systemic Change and the Chair of Transforming Practices of the Department of Industrial Design at the Eindhoven University of Technology.

Jeroen Peeters

Jeroen is a Senior Design Researcher at the unit Societal Transformation, part of the department Prototyping Societies at RISE Research Institutes of Sweden. Within this capacity, he has contributed to a variety of national and international research and design projects with public and private sector actors. Since 2021, he is also a visiting researcher at the Systemic Change Group at the Department of Industrial Design at Eindhoven University of Technology. Jeroen´s research work focuses on how to design for engagement and the use of design methodologies to develop insights and knowledge of complex societal challenges. This work is centered around the design of proposals that make societal transformation experienceable with the aim of allowing stakeholders to feel and thereby understand what is necessary for a transformation to take place. Jeroen holds degrees in Industrial Design from Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands (2012) and a PhD in Design Research from the department of Informatics at Umeå University in Sweden (2017).

Picture © Murat Erdemsel

Caroline Hummels

Caroline Hummels is professor Design and Theory for Transformative Qualities at the department of Industrial Design at the Eindhoven University of Technology (TU/e). Her activities concentrate on designing for and researching transforming practices. She is linking nowadays challenges and complexities of quintuple helix partners, with probably, plausible, possible and preferable futures in the upcoming 5 – 100 years, through designing alternative ways to engage in complex socio-technical systems. She is thereby interweaving theory and practice, by developing with her team a design-philosophy correspondence, in which both disciplines mutually inform each other to address societal challenges.Caroline has always worked at the forefront of design research to develop the discipline, push its boundaries and address societal challenges. She is co-founder and steering committee member of the Tangible Embedded, and Embodied Interaction (TEI) Conference. She has been at the forefront building the Research through Design (RtD) field and community in the Netherlands. She is ambassador for co-creation and participation of the Key Enabling Methodologies (KEMs) for mission-driven innovation, advisory board member of the Dutch Design Foundation, associate editor of the Journal of Human technology Relations, and editorial board member of the International Journal of Design. Picture © Marike van Pagée

Pierre Lévy

Pierre Lévy is professor at the National Conservatory of Arts and Crafts (CNAM) in France, holder of the Chair of Design Jean Prouvé, and researcher at the Dicen-IDF lab. He is interested in the correspondence between reflection and design practices, pointing towards transforming practices and sciences. His research mainly focuses on embodiment theories and Japanese philosophy and culture in relation to designing for the everyday. Previous to his position at CNAM, he has been researcher at the University of Tsukuba and Chiba University in Japan, and assistant professor at Eindhoven University of Technology. He holds a Mechanical Engineering master’s degree (UT Compiègne, France), a doctoral degree in Kansei (affective) Science (University of Tsukuba, Japan), and a HDR in Information and Communication Sciences (UT Compiègne, France). He is also co-founder and former president of the European Kansei Group (EKG) and coordinator of the Kansei Engineering and Emotion Research (KEER) Steering Committee.

Picture © Nami Lévy

Daisy Yoo

Daisy Yoo, PhD, is an assistant professor at the Department of Industrial Design at the Eindhoven University of Technology in The Netherlands. Her primary research focus is on designing for public services and social sustainability. In her prior work she investigated issues of participation, inclusion/exclusion in politically contested design spaces – spanning from local issues concerning the co-design of public transportation service to global issues concerning the transitional justice for Rwanda in the aftermath of the 1994 genocide. Such work, entangled in the web of complex social dynamics, raises methodological and ethical challenges, calling for new design methods, toolkits, and theories. Prior to TU/e, she held the postdoctoral fellowship on participatory design at the Aarhus University in Denmark. She holds a PhD in Information Science and Human-Computer Interaction from the University of Washington, where she was advised by Batya Friedman of the Value Sensitive Design Lab. She received her Master’s in Interaction Design from Carnegie Mellon University, and her Bachelor of Science in Industrial Design from Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST).

Picture © Vincent van den Hoogen

Design is an attitude

Forbes Top 50 Women in Tech, Strategy Advisor to European Commision and Parliament and Founder of ElectroCouture, ThePowerHouse and FNDMT, Brussels

Design is an attitude

The renaissance of an interdisciplinary mindset

This article pays homage to the legacy of artist and Bauhaus professor László Moholy-Nagy and calls for a renaissance of his mindset, a mindset that incorporated new and revolutionary ideas about technology, education and attitude.László’s mindset is perhaps best encapsulated in maxims that abound in his prolific writing and which are pithy, catchy and easy to adopt as principles of design. Design is an attitude. Everyone is talented. László’s ideas about design were—and still are— democratic and inclusive. Everyone who can get involved in the design process should be involved—and that’s especially true when confronting the complex issues we face today such as sustainability. László was relentlessly experimental, but he was also very practical and his ideas very practicable. He documented his work fastidiously and he wrote prolifically, meaning his ideas, his guidance could be put into practice.

What is design?

So, what is design? Wow, we could talk for 10 hours—for 10 years!— about this. But what we can say for certain is that design is always an opportunity to improve. And for the designer, opportunities abound—it’s just a matter of seeing them. Looking, for instance, at discussions around sustainability, we need to find new solutions and new ways to tackle problems in order to build a better world. We need to solve problems created by old systems. (Though imagine that we had actually tried to avoid the problems before they had turned into the big issues they are now…)The sort of design I’m interested in is inspired by the Bauhaus. The Bauhaus was not just a school of design—it was away of working, of living, of being. One of my favourite aspects of the Bauhaus, a school of which László founded in Chicago, is the training that all of the students had to go through. Every student needed to know all of the machines in the workshops—not only how to use them, but also how to maintain them and how to repair them. Isn’t that wonderful? When you know how things are made, how machines work, it gives you power and freedom at the same time.

"Everyone is talented"

Back then it was the sewing machine. Today it’s the computer. Both have generated an impact beyond their intended purposes. I call this potentially extended impact #reprogramthemachines, because every machine can do more than the purpose it was originally designed for. It’s the same with our brains. We can do so much more than what we’ve been trained for before. And everyone is talented. László argued that, so long as they are interested in and dedicated to their work, people can tap into their natural creative energies. That means everyone can get involved. And in the case of the complex issue of sustainability, everyone—every possible angle—should be involved.We also need to look in from the outside. The fashion industry, for example, is an industry which was siloed for a very long time, relatively protected from outside opinion and criticism. A t-shirt requires around 25,000 litres of water in order to it. There is something very wrong with this picture but sometimes it takes an outside view to see this wrong.

Looking at other industries which have been disrupted in the last 10, 15 years—transportation, music, movies—the startups that disrupted them didn’t emerge from the traditional industry. Spotify, for instance, didn’t emerge from traditional radio. Instead, these companies were founded by people who were frustrated with the status quo and who dared to question it, asking, Why don’t we try things differently? They used tools to fix the problem, digital tools, and involved people from across disciplines. When everybody is talented, everyone can get involved. No elite, no club, just an equal playing field.

"Designing is not a profession but an attitude”

I love the emphasis on attitude in the Bauhaus. Everybody can have an attitude, it’s a totally level playing field. It’s about lifestyle, it’s about seeing opportunities everywhere. Everyone should and can have the attitude to change and to design. And everybody can and should have the opportunity and attitude to be sustainable.

That means it is the designer with the right attitude who brings everything together.

The problems we have to solve now—and the problems we need to avoid in the future—are very complex and very diverse. They’ve been created because industries have been trapped in silos with no communication between them. So, for me, it’s the designer with attitude who can bring everything together—and we are all designers. We are bridge-makers, traversing industries, silos, technologies and mindsets to bring everything into a coherent and intelligible picture.

"The illiterate of the future will be the person ignorant of the use of the camera as well as the pen”

Remember László’s telephone pictures? Those pictures started a whole new discussion: What if, all of a sudden, a designer uses technology to create art? Is he still an artist?. Back then, photography was a new technology and László completely embraced it. But let’s not forget the pen which was, at some stage in history, a new, super smart piece of technology. The camera is to us now what the pen was for László. For us, the camera is a standard, familiar tool, like the pen. Perhaps new technologies like algorithms and artificial intelligence perhaps have a similar novelty for us that the camera had for László. The question is how we work together to use these tools. So, ladies and gentlemen, how do we do this?

Work. Go and travel. Go and talk with other people if you’re an architect or builder, in the loosest sense of those words. Or if you’re a writer, a musician, a content creator. Explore space, explore our oceans. Have you ever talked with a programmer, a software engineer or a data architect? I highly recommend it because a great piece of code can be as exciting as a novel and as impactful as a symphony. So, wherever you go, whatever you do, do something different. Talk with other people. Make things better, together.

Lisa Lang

Lisa Lang has gained recognition as one of Forbes Europe’s Top 50 Women in Tech, and has been listed as one of the 50 most important women for innovation & startups in the EU.She founded highly recognized companies like ElektroCouture, ThePowerHouse and FNDMT who are dedicated to push innovation within the creative and innovative industry eco systems. Lisa Lang is a direct adviser for creative industries, digitalisation and entrepreneurship for the European Commission on several high-level advisory boards, including Pact for Skills, Industrial Forum and the US/EU Trade & Technology Council.

Lisa Lang is on the advisory board to the Zurich university of arts as well as a policy advisor for Fashion Innovation Centre Sweden. She regularly teaches business and innovation strategies at the Porto Business School and has been given guest lectures at TEDx Athens, KryptoLabs Abu Dhabi and Oxford University.

Picture © VOGUE Greece

Decolonial Thinking vs. The White Savior Industrial Complex (a Podcast)

Founder of Fashion Africa Now, interdisciplinary fashion curator,

creative producer & African fashion advocate

Decolonial Thinking vs. The White Savior Industrial Complex

Colonialism is over, but the colonial continuities are still present. Colonial reappraisal is still in its infancy and, following the Black Lives Matter movement, is increasingly calling for clarification. In the cultural landscape, there is an increasing presence of the topic, but the media and textile and clothing industry still show restraint. In the fashion and design scene, approaches with a decolonial orientation have developed in recent years that critically question the fashion and design system. A booming fashion scene in Africa and its diaspora is gaining more and more international attention, breaking stereotypes, doing away with clichés and reclaiming narratives. What is the role of African fashion and design aesthetics in decolonisation? In an increasingly fast-paced world where tradition meets modernity and innovation is unstoppable, a new interplay is beginning.

How can a European rebirth be shaped today? The active work of decolonial thinking is a first step to create a new definition and awareness to give space to sustainable and equal perspectives. One approach is deconstruction.

The values and history of design are taught through a Eurocentric canon, accepting work predominantly by European and American male designers, which forms the basis of what is considered „good“ or „bad“. This authority has the effect of undermining the work of non-Western cultures and people from the Global South so that, for example, Ghanaian textiles are classified as craft rather than design. Classifying traditional craft as something other than modern design deems the history and practice of design of many cultures inferior. We should strive to remove the conflation of craft and design in order to recognise all culturally important forms of making.

Redefining old ways of thinking

It is necessary to break down and redefine old ways of thinking. That is why we are reclaiming the narrative: A new generation of designers of African origin are rethinking contemporary „African fashion“. A self-confident self-image and an aesthetic from an African perspective is presented—beyond the (neo)colonially influenced thought patterns and beauty norms. This is the beginning of „Deconstruct Fashion“. That means the breaking open and reinterpretation of fashion. A new confrontation, historical and contemporary, guided by BIPoC (Black, indigenous and people of colour) perspectives. It is important to understand the origin of African indigenous fashion and the traditional aspects in order to interpret it correctly. Due to its universalist thinking, the previous design rhetoric excludes and ignores alternative productions of knowledge.

Actively and critically engaging with the history of colonialism will open our eyes to how power structures have shaped contemporary society and how they dominate our understanding of design and aesthetics. The realisation that capitalism is „an instrument of colonisation“ and therefore almost impossible to truly decolonise in Western society.

Beatrace Angut Lorika Oola

Founder of Fashion Africa Now, interdisciplinary fashion curator, creative producer & African fashion advocate

Beatrace Angut Oola has spearheaded the conversation around inclusivity, curated exhibitions, for example „Connecting Afro Futures. Fashion x Hair x Design“ together with Cornelia Lund and Claudia Banz (Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin, 2019), has realised fashion shows, initiated POP UP formats, moderated talks in Germany and worked on knowledge exchange projects in African countries and has also championed best in class practitioners in the diaspora. In 2012, she founded the first high-end fashion platform for designers of African origin (Africa Fashion Day Berlin) and a creative agency (APYA) in Germany; this was followed in 2016 by (Fashion Africa Now), an online networking and information platform, serving as a bridge for African creatives to Germany. Last year was the birth of the Fashion Africa Now podcast, which additionally offers an exchange on the social perception in the global north of fashion from Africa and the diaspora. She has also been a guest lecturer at the Hochschule für Künste in Bremen since October 2020. Furthermore, she is one of the global pioneers of the African fashion movement and stands for inclusion, representation and diversity in the fashion industry.

Ten Hypotheses on Society-Centered Design

Professor at Graz & Kassel University, Culture & Design Consultant, Manager & Networker

1. A world in transformation

Our world is currently undergoing an enormous transformation. Above all, young people who are aware of the negative effects of today’s economic model are discussing new approaches to the world: The inequality between the first, second and third worlds meets with criticism and measures are demanded to stop the increasing destruction of our environment. A growing number of people are participating in social initiatives and working hard to make the world around them a better place.

2. Design and its great social responsibility

Design has played a crucial role in the developments of industrial societies over the past 150 years, thereby affecting man and his environment. Subsequently, designers are aware of their great responsibility in using creative means to resolve the problems we are faced with now and in the future.

3. User-centered design

Until about 30 years ago, the design process was neither interested in man nor environment; it was chiefly about achieving entrepreneurial success and profit maximization. However, from the turn of the millennium on, the idea gained popularity that the design process should take account of human needs and the capabilities and behavioral patterns of individual users. User-centered design came to be the new creed in the design scene.

4. Individual success versus long-term consequences

However, in a globalized, networked world, anything that could benefit one individual could harm another – not to mention our planet. The negative consequences of a creative method that focuses too much on the individual, at the same time ignoring the political and societal dimension of design, have now become evident.

5. A new paradigm?

As early as 1971, Papanek in his book “Design for the Real World” criticized the trend toward producing “useless, potentially harmful, irresponsible and questionable items of mass consumption” from an ecological point of view. He spoke out against irresponsible design and developed a radio for the third world based on an old tin can.

6. Society-centered design

50 years on, Papanek’s approaches are now gaining increasing approval. Many designers are no longer prepared to pander to wealthy clients in their search for aesthetic segregation, but are beginning to question their role in the context of the widening gap between rich and poor and in the light of environmental problems. They participate in social movements, support grassroots initiatives and try to contribute to improving the world as quietly and unobtrusively as possible.

7. Society-centered design from a holistic perspective

Designers must be aware that they are shaping ecosystems and not just individual applications. They need to look beyond the individual user and immediate financial success in order to develop the best possible solution for man, society and nature. “Society-centered design” is sourced precisely from that design context. It not only addresses users and business, but also society and environment and their various different interdependencies.

8. Society-centered design – a better business strategy

Enterprises, too, feel that it is time for a new approach in product development. Today’s consumers are more informed and critical, they check on the item’s production process and if employees are fairly treated, or on the attitude of companies and brands towards social questions. Many people want to contribute to community welfare and environmental protection. Accordingly, they seek businesses and designers that offer products and services in line with their own mindset. Consequently, society-centered design is no idealistic ideology, but rather a competitive advantage for entrepreneurs who wish to reach out to the public (and realize profit).

9. Society-centered design: a new mindset

In order to do justice to society-centered design, we not only need a new mindset, but also committed strategies and augmented methods. Instrumental to the concept would be to additionally integrate the needs of non-human stakeholders – such as animals and the environment – in the design process. To that end, we require knowledge and creative technologies from human-centered design and usability, as well as from the realm of ecology, environmental sciences, sociology and philosophy.

10. The future of design

Primarily, designers need to internalize holistic thinking and let it flow into their daily work, besides convincing businesses and clients of how essential that approach is. Society-centered design is not an idealistic bubble, but a real competitive advantage for enterprises. The key to success is to get together and develop a new design approach. And think ahead: it all depends on collaboration — between politics, science, the economy, designers, activists and citizens — in order to find solutions and achieve and implement this new idea of design in the near future.

Prof. Karl Stocker, PhD

Professor at Graz & Kassel University, Culture & Design Consultant, Manager & Networker

Karl Stocker, PhD., historian, exhibition director, information designer, chair of bachelor programme Information Design (2004-2021) and Master programme Exhibition Design (2006-2021), head of Institute Design and Communication at University of Applied Sciences Graz (till 2021), professor at the Graz University (since 1988) and Kassel University (1996/97), founder and director of Bisdato Exhibition & Museum Design (1990-2021), author/editor of books and scientific contributions, manager of scientific research projects, director of exhibitions, ambassador of Graz UNESCO City of Design.

Picture: © Lex Karelly

It’s not about saving the world!

Cultural Manager, Creative Industries Expert and Design Aficionado

IT'S NOT ABOUT SAVING THE WORLD!

Renaissance is a word that you could associate with many things, on different levels and in various disciplines. If the concept of a “New European Renaissance in the Making” is to be discussed comprehensively at this point, then we should nevertheless keep in mind relevant historical landmarks and, to an even greater extent, the humanistic and social impact of the Renaissance, simply because we should be aware of the consequences. Accordingly, what could be subsumed under that term—despite all of its varied manifestations as Renaissance, Humanism or Reformation—is the concept of radical change, of a paradigm shift. We shall talk about that below when Creative Industries shift into the focus.

In recent decades, the need for change—you could also call it a restart or a reset—has become increasingly virulent and perceptible, especially in the creative sector and, above all, in the field of design. What had initially begun as a rather vague feeling of uneasiness is now becoming a visible constant in societal discourse. Behind it is the vast transformation of society and media which has caused radical change to our living and working environments. In order to present evidence for those transformations, you do not necessarily need to mention an epochal happening like a pandemic, although the pandemic has certainly sharpened our perspective on those upheavals. In that respect, then, there is no better time than now to address the “New European Renaissance in the Making”. And creativity will play a crucial role in it.

the human race will not survive without creativity

The idea is as simple as it is provocative: It’s not about saving the world because the planet will outlive the human race—but the human race will not survive without creativity. Now, at this point we could maintain that things have always been that way, and that is, of course, correct. There is, however, one fundamental difference: Today, in the 21st century, we are aware of the situation. It is no longer about mere inventions that could make something easier, faster or bigger, but rather about avoiding man’s extinction. That may sound somewhat pessimistic, but a glance at today’s state of the world (climate change, a migration crisis, and so on) seems to justify this dramatic momentum. In view of that, many people, above all younger people, are no longer prepared to uncritically perpetuate the quasi-natural mechanisms of life and work. Hence, the above-mentioned change can only happen through us and it will only succeed if we—which at first glance seems to be a paradox—do not put man, the individual person, at the centre of considerations.

To that end, we are in need of design, but the kind of design that can shoulder the current challenges. Over the past 150 years, design has taken on growing social responsibility as a key player in the developments of industrial society. If design had previously been perceived as a predominantly aesthetic and visual amenity serving the financial success and profit maximisation of big business, towards the end of the 20th century it started to become a tool for human needs that accounted for the capabilities and behaviour patterns of individual users. So-called user-centred design was suddenly in the limelight, triggering a process of unprecedented individualisation and commercialisation that completely disregarded the political and societal dimensions of design. However, that met with prompt criticism. As early as 1971, Victor Papanek in his book Design for the Real World criticised the trend towards producing “increasingly useless, potentially harmful, irresponsible and—from an ecological viewpoint—questionable items of mass consumption.” He spoke out against irresponsible design and developed a radio for the Third World based on an old tin can.

The answer to the question as to whether the time is ripe for revolution is, unequivocably, Yes

Fifty years on, Papanek’s approaches are meeting with increasing approval. Many designers are no longer prepared to pander to the demands of wealthy clients with aesthetically exalted tastes, but are instead beginning to question their role in the context of a widening schism between rich and poor and in the light of environmental problems. They participate in social movements, support grassroots initiatives and try to contribute to improving the world in a simple and quite unobtrusive way. This development marks a distinct turning point in the discourse on design, reflecting new standards that will determine how we shape our environment. A fundamentally different way of thinking is born: In place of nurturing individualism to the point of perversion, a genuine search has started for meaningful creative activities that focus on the bigger picture to deliver the best solution for man, society and nature. This approach to design will revolutionise future creativity and the future of creativity. It is about society-centred design that not only caters to users or to economic considerations, but above all to society and our environment.

The answer to the question as to whether the time is ripe for revolution is, unequivocably, Yes. It is high time and we can prove that by the fact that this attitude towards design has already arrived on the economic level. Businesses are experiencing a growing client demand for products and services that do not necessarily have to offer “more” (faster, further, bigger, more expensive), but should be fundamentally “different”. Those enterprises realise that they could have a competitive advantage if they pursue that strategy, which means that one of the toughest barriers for the widespread acceptance of society-centred design has been overcome.

Of course, that does not exempt us as representatives of Creative Industries—who often negotiate the topic on a highly theoretical level—from the responsibility of actively promoting this approach and introducing it with greater vehemence to enterprises. From the very start, we must rule out any suspicion that the matter could again end up in self-referencing ritualised academic discourse enriched with theoretical considerations on university level without, however, yielding any practical effects. The order of the day is, therefore, to act now and to implement the developed concepts at once. We know from experience that there is no lack of ideas, but rather a certain hesitance to implement them.

creativity as a maxim for future actions

Creativity and Creative Industries play a crucial part in that respect because they often allow unexpected solutions to unfold. Human creativity therefore makes the big difference, and again, it is not just about intelligence that could be made by a machine. There is no doubt that artificial intelligence will have an enormous impact on our future life. Creativity, however, is a profoundly human phenomenon that we should maintain at all costs. But precisely because is associated with a quantum of uncertainty, creativity—acting creatively—is rarely planable in a strict sense. We therefore have a dilemma. Creativity cannot be practiced to produce a solution, like an athlete training for a competition. For that reason, we are required not only to allow creativity to flourish on all levels, but also to actively promote it. Essentially, it is about augmenting the potential for creativity to a maximum and letting it permeate all areas right to the finest ramifications and niches of life. Maybe the solution for one of many challenges will originate from there. At the same time, it is a procedure of trial and error as well as creatio ex nihilo. The latter, i.e. creation out of nothing which is known from early Christian cosmogony, also found its way into modern physics: Stephen Hawking, too, argued that the Universe could have been created out of nothing—thus illustrating the principles of creative work. That would not only explain creativeness most aptly—it would also restore creativity to our lives as a maxim for future actions.

Eberhard Schrempf

Cultural Manager, Creative Industries Expert and Design Aficionado in Austria

Eberhard was vice-artistic director and managing director of the European Capital of Culture – GRAZ 2003 and is the director of the „Creative Industries Styria“ network since 2007. In this function, he developed the festival „Design Month Graz“ and was responsible for the successful application of the city of Graz to become a UNESCO City of Design, as well as developing many innovative projects and formats. Schrempf advises numerous companies and institutions in the areas of creativity, design and management. He is lecturing at the Institute for Design and Communication at the FH Joanneum, University for applied sciences, a lateral thinker and guest speaker at international conferences.

Picture: © Raneburger