The cocktail of challenges of disadvantaged in crisis

Ruth Daniel, CEO of In Place of War and Honorary Research Fellow at University of Manchester; Teresa Ó Brádaigh Bean, Leader of research activities at In Place of War and Honorary Research Fellow at University of Manchester

The cocktail of challenges of disadvantaged in crisis

Making the case for the civic role of the creative and cultural ecosystem in a Renaissance

The ongoing COVID-19 Pandemic has had a devastating impact on communities around the world. Whilst in Europe many have enjoyed the cushion of working from home or social protection mechanisms (special benefits and unemployment protection), disadvantaged communities in Latin America, Africa and the Middle East have been left vulnerable on all fronts. Operating in mainly the informal economy or in precarious employment, living in overcrowded housing, lacking access to information or PPE (personal protective equipment), and enduring some of the strictest and militarised lockdowns in the world presented these communities with a cocktail of challenges. This piece builds on the work of In Place of War in sites of conflict in the Global South for over 17 years working with grassroots arts-based peace-building as well as 120 cultural leaders and gives witness to the role of community arts organisations in civic engagement, using the arts to mobilise communities to make positive social change.

Picture above: break dance performance in a sports ground, Medellin, Colombia. Copyright: Leonardo Jimenez

COVID-19 was a further catalyst for community arts-based social mobilisation and civic engagement to tackle immediate issues of food insecurity, lack of sanitation, wellbeing, and public health awareness and school closures. Many of these challenges faced by communities were not a consequence of the virus per se; rather COVID-19 has exacerbated critical issues the communities were already facing. Working in partnership with our network of change-makers, drawing on their local knowledge, existing community relationships and understanding of how best to respond to the pandemic, we supported them in delivering direct, bespoke assistance, determined and led by those located in beneficiary communities. These locally-led processes resulted in a range of responses from the creation of community kitchens to mobile sound systems and online fundraisers and concerts to provide economic assistance to artists and the wider communities. Despite the array of projects, they all reaffirmed our understanding that art can be key in fomenting civic participation and positive societal change.

Despite or because of COVID-19: a new role for social enterprises

This process also demonstrated how, with a small amount of funding, informal, grassroots organis-tions rooted in communities that are often underrepresented in the cultural sector and who can’t normally access funding can lead to long-term positive outcomes. This included the development of sustainable social enterprises. Thus, this invites reflections in the European context and beyond about the importance of embedding participatory grant-making for grassroots arts organisations as a strategy to create a more inclusive and diverse creative ecosystem that supports arts-based sustainable development.

Hunger isn’t in Lockdown: COVID-19 in the Global South

As COVID spread, and lockdowns were imposed globally, our network of change-makers provided grim insights into the impact of COVID-19 on some of the world’s most disadvantaged communities. Here is a snapshot from artists and cultural practitioners on the ground in Latin America, Africa and Asia in April 2020.

MC Benny, Hip Hop artist, Northern Uganda: “People are living in fear, many are testifying that this is worse than a physical war. Our team has already seen that government forces have been using excessive force to enforce lockdowns”

Nathalia Garcia, Elemento Illegal, Medellin, Colombia: “Communities in El Faro, an informal neighbourhood on the outskirts of Medellin where many displaced families forced to flee violence have been severely affected by COVID. The area is home to 400 vulnerable families living in dire conditions, working in informal and precariousemployment. Lockdown has left them unable to generate income and 98% of them are struggling to cover their basic needs with hunger being the most pressing issue. Preventing the spread of COVID in the area is further compounded by lack of basic sanitation and hygiene products.”

Vijay Kumar, India: “There is simply no support from the government, some families are on edge of starvation during these days.” Our team notes, “India has some of the most extremely high-density urban populations, social distancing is simply not an option for most of these people, and the consequences of lockdown are costing lives through hunger and lack of medicine.”

Robert Mukunu, Mau Mau Arts, Kenya: “A young boy was shot by police on the balcony of his home in Kiamaiko, Nairobi, because ‘he was out during the curfew’ which seems like a dark irony that a citizen was killed by police who were ensuring he was indoors to protect him from COVID. Questions still remain unanswered on why the government is charging for treatment of corona-related ailments as well as the use of testing kits and masks donated to the government.”

Re-birth in the midst of lock down? How to leverage support and funding from the Music Industry in crisis conditions

Whilst IPOW’s work has focused on supporting and building networks with grassroots artists in the Global South, the organisation has also developed relationships with commercial music industry partners. During the pandemic, given the devastating impact of COVID on the cultural sector, these organisations were keen to support artists and cultural practitioners. Thus, working in partnership with In Place of War, small grants of $500 to $2,000 were made available to the change-maker network.

Setting up an innovative process for participatory grant-making, locally informed decision-making and implementation.

A call for applications was sent to our change-maker network via Whatsapp in French, English and Spanish, resulting in 45 applications. The application process was open in which applicants had to explain the impact of COVID on their community and their ideas to address these issues. A small panel from the In Place of War Board and team reviewed applications, selected recipients, and funds were distributed promptly, having immediate impact. The overall process took only two weeks, including the due diligence process required to meet charity regulations. Given the geographical spread and diverse contexts in which artists operate, projects ranged from tackling food insecurity through the establishment of community kitchens, bakeries and allotments, public awareness campaigns about preventing the spread of COVID-19 using visual arts, and issuing grants to artists.

Change-Maker case studies

Delhi, India

Vijay Maitri is a theatre practitioner from the Kathputli Colony in Delhi, India.

Due to lockdown, this community of 12,000 performing artists (the lowest caste in India, considered to be the criminal caste) who live in slum conditions, were unable to earn money and therefore unable to afford any food or access PPE.

Vijay organised a food and PPE distribution centre in the neighbourhood and using the IPOW grant distributed food and PPE to 12,000 people.

Picture right: Vijay organising food distributions, Copyright: Vijay Kumar

Medellin, Colombia

Alejandro Rodriguez is an MC and music producer and part of Old Guns, a hip hop collective from Comuna 13 in Medellin, Colombia.

Comuna 13 is a disadvantaged neighbourhood suffering from high levels of poverty and violent gangs. During the lockdown many residents could not make a living as they work in the informal economy as street vendors, builders, collecting rubbish and recycling. Thus, lockdown left them struggling to access food and essentials.

Picture left: Ciudad Comuna interview, Copyright: Ciudad Comuna

With the In Place of War grant, Old Guns decided to develop a community kitchen and allotment to address the issue of food insecurity in the area. They secured a building, partnered with a local community organisation, got permission from the gang leader who controls the area and enlisted an army of volunteers to work in the kitchen. During lockdown, the kitchen served 750 meals a week to vulnerable members of the community using produce from the community allotment.

Picture left: Kitchen serving meals during lockdown, Copyright: Alejandro Rodriguez

Caracas, Venezuela

Tiuna El Fuerte is an arts organisation located in El Valle, Caracas, Venezuela.

People living in tower blocks in the surrounding neighbourhood felt isolated and disconnected during lockdown, resulting in a decline in mental health.

Using the grant from In Place of War, Tiuna El Fuerte set up a mobile sound system and radio station, which travelled across the streets playing music and sharing messages over the sound system from loved ones across the community, helping people feel less isolated. They estimated that they reached over 20,000 people in two weeks.

Picture right: Tiuna El Fuerte’s Radio Verdura in the streets of Caracas, May 2020. Copyright: Tiuna El Fuerte

Cali, Colombia.

Marimbea is a cultural organisation based on the Pacific coast that works to promote Afro-Colombian culture through tours, performances and workshops. Due to the pandemic and lockdown, the community were unable to work and lacked access to basics. Using a grant of $1,000, Marimbea organised a series of online events, performances and workshops, paying the artists to participate and charging audiences to engage with the content. The events generated $2,000 in revenue and led to the development of a new digital content platform offering cultural experiences online.

Picture left: Promotion material for online workshop, Copyright: Marimbea

Reflections: What to learn for the idea of a Renaissance

These case studies provide interesting insights into the civic role of arts organisations in mobilising to address critical needs of local communities during the pandemic. This is hinged on a number of features. These organisations are committed to a place; often taking place in public spaces such as playgrounds, community centres, parks and schools, it is part of and shapes the local landscape. It is rooted in and part of their communities and thus artistic practice is designed by and for those communities. Given this, the art responds to the needs and aspirations of this community, and nurtures and celebrates the talent within the community.

Civic participation and artistic practice can not be divorced

This is a people-centric and local approach using artistic practice to facilitate human development, promoting positive values and social interaction and building communities. Given this, civic participation and artistic practice cannot be divorced: they are enmeshed and develop a symbiotic relationship. Art is a tool to engage communities which through participation leads to new artistic work and a more inclusive and diverse creative ecosystem designed to develop the community.

Indeed, one of the commonalities between these responses to the lockdown was that the organisations improved their standing within their local communities. Their work during the pandemic has elevated their status and visibility within the community and beyond. The creation of Trackside’s bakery and Marimbea’s digital cultural experiences are representative cases of this.

Picture right: Theatre performance about disability in Northern Uganda, Copyright: Mono Grande

Radically nurturing artistic talents—and their aspirational community

We believe that, as in the case of our change-maker network, identifying and nurturing existing talent and projects in communities is key in developing genuine arts projects that respond and evolve to meet the needs and aspirations of the local community. Thus, rather than prescribing themes and agendas, offering support for the evolution of organic arts based community is of paramount importance.

Picture left: Dance class in Medellin Credit_Mono Grande, Copyright: Mono grande

Be innovative about funding social innovation

Similarly, developing more inclusive and open funding streams to enable grassroots, informal organisations to access funds to create civic arts projects is also key. We adopted a participatory grant-making model that allowed art organisations to develop responses that were tailored to their experiences and knowledge of their communities. They were not constrained by our preconceptions of what was the most critical need and this is clearly reflected in the range of responses the organisations developed. Small grants were distributed to informal groups and collectives as well as local NGOs which we were able to award without the need for clumsy and prohibitive due diligence processes, whilst crucially complying with charity commission regulations. Thus, in sum, the pandemic has illuminated the primordial role that local grassroots arts organisations can play in addressing critical issues facing communities, especially in times of crisis. They can be responsive and resourceful, generating immediate and real impact with little funding. This therefore invites us to rethink how we understand community arts projects beyond short-term interventions that respond to fleeting policy agendas and political strategies.

How can the cultural and creative sector foment grassroots, locally-led civic arts that showcase and celebrate talent in towns and cities in Europe both during and beyond the pandemic? How can we create inclusive and accessible funding processes so that such informal groups can develop and sustain their practice whilst generating long-term positive outcomes?

The creation of diverse networks and long-term relationship-building connecting commercial partners, governments, formal cultural institutions and grassroots collectives is key to fostering long-term arts-based social transformation in our communities—a transformation the green and digital transformations cannot do without—like, for example, the New European Bauhaus, the latest initiative of EU President von der Leyen highlights. Learning from the Global South how to empower arts-based social transformation in communities might strengthen a Next Renaissance in Europe while preventing one of its major risks: Of being a Revolution for the Privileged.

Links

Creativity Conquers COVID- A short documentary about the how IPOW’s change maker network responded to the COVID lockdown

Ruth Daniel

Ruth is a multi-award winning CEO, activist and change-maker. Inspired by the transformative use of hip-hop in the drug cartels of Medellin, Colombia, when a young MC said: ‘If it wasn’t for hip-hop, I would be dead. Hip-hop gave me another option and I’m truly thankful for that.’ Ruth believes art has a capacity to make change in the toughest of contex From guitarist at the age of 8 to record label owner, band manager, fundraiser, international cultural activist, entrepreneur, educator, influential speaker (TEDx) to prestigious award winner within a national arena (Social Enterprise of the Year & Manchester Woman of Culture to name a couple), Ruth’s passion to empower people to build their own positive futures through creative entrepreneur programmes, the development of cultural spaces and artistic collaboration shows no boundaries in terms of fields of work.

Picture © Katie Dervin

Teresa Ó Brádaigh Bean

Teresa Ó Brádaigh Bean is head of research and learning at In Place of War, a global charity that works to support grassroots arts based social change processes in sites of conflict. Her research interest and practice has focused on hip hop as a social movement, grassroots arts education, creative entrepreneurship in sites of conflict and community arts based peacebuilding. She has undertaken a number of research project exploring arts based social change processes mostly recently as a researcher on the the Art of Peace led by Prof. Oliver Richmond at the University of Manchester. She has played a key role in developing In Place of War’s education programmes. As a qualified teacher, she wrote CASE (Creative and Social Entrepreneur Programme). CASE was one of the five shortlisted finalists for the inaugural UNESCO-Bangladesh Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Creative Economy Prize in 2021. It was awarded the Outstanding Contribution to Widening Participation at the University of Manchester’s Making aDifference Awards in 2017. The programme has been delivered in 14 countries including Bosnia, Uganda, Colombia, South Africa and the MENA. Teresa is an Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Manchester and a member of the Global Coalition on Youth, Peace and Security (GCYPS) a UN Inter-Agency Network.

Picture © Alexander Butcher

Our Ode to Creativity

Dr. Matthias Röder, Managing Director of Karajan Institute, Co-Founder of Sonophilia Foundation; Seda Röder Founder of Sonophilia Foundation, Salzburg

Our Ode to Creativity

In 2019, Michael Schuld of Deutsche Telekom asked whether an AI could be built to finish Beethoven’s 10th Symphony—a revolutionary homage and a birthday gift to Beethoven by the Bonn-based company bringing together technology, arts and communications. In this piece we reflect on the aspirational benefits of a “creative AI” and the reactions of recipients from different milieus. Although general audiences embrace the endeavour, cultural conservatives argue to exclude AI from entering the genius-oriented realm of creativity. Fear seems to be omnipresent, oblivious to the fact that Beethoven AI is a tool—like printing in the 15th century. In this short essay we make the case of how to put AI-supported Art to use for a human-centric Renaissance.

Picture above: Copyright Deutsche Telekom / Norbert Ittermann

Finishing Beethoven’s 10th Symphony with AI support would be monumentally complex—we knew right away. This is for two reasons. First, there exist only a very small number of sketches for the symphony and they are for the most part in a fragmentary state. Therefore, understanding Beethoven’s intentions for this 10th symphony is difficult. Second, honouring what Beethoven had already written, but keeping in mind his incredible versatility in working with musical material, required a very flexible and unique kind of AI that did not yet exist. As we started the project, however, a third complexity emerged to outtrump all others. Beethoven was seen as one of the pinnacles of human creativity and we were receiving criticism even before one tone was played: How could we even dare to create music with an AI that could compare with Beethoven’s music?

Two years later, in October 2021, Beethoven X – The AI Project was premiered, at Deutsche Telekom’s headquarters in Bonn. Thousands of people around the world followed the live stream along with hundreds in the audience. Not one person in the crowd was able to tell where exactly the sketches of Beethoven ended and where the music of the AI took over. Standing ovations filled the hall for many minutes… Music aficionados, technology enthusiasts and distinguished media outlets such as CNN, BBC, BILD and many more from around the globe seemed to love the result, while the album entered the German pop charts.

Nonetheless, following the premiere, a heated discussion broke out.The conservative feuilletonists and hardcore traditionalists labeled Beethoven X as “sacrilege” and were particularly bitter in their judgement. Going over the music motif by motif, they discussed whether our AI matched Beethoven’s “genius” music, or whether it was just an unemotional imitation of the original—often confusing and criticising the original fragments with music produced by the AI. The discussion however showed striking similarities to the criticism that others have received for creating their completion of Beethoven’s 10th symphony. That’s when we realised that the whole debate was clearly not about the music itself nor about the capabilities of the technology—it was about excluding AI (and sometimes even humans) from entering the genius-oriented realm of creativity.

But Beethoven X heralds a future where there are no barriers of entry into the ivory tower of arts. It foreshadows a new kind of Renaissance that is all about democratising creativity for all rather than making it a privilege for a few. Most importantly, Beethoven X aspires to be part of a future where humans and machines interact productively so that more people can harness the benefits of technological tools to unleash creativity, to self-actualise and to contribute to humanity. Technologies are advancing rapidly. Therefore, unleashing their potential for the greater good is, quite frankly, a pressing matter. We should, perhaps, be maximising the creative potential in the world with much more urgency. Consider this: according to the numbers compiled by the Austrian Statistics Agency, only 0.02% of the entire world population is working in any innovation and creativity-related field—R&D, environment, food, societal innovation, arts… you name it!

But can it truly be that only one in 5,000 people are actually creative? Can it truly be that only one in 5,000 people can contribute to innovation or to arts? Of course not!

We live in a world obsessed with not wasting resources, yet when it comes to human potential, we seem somewhat complacent. Considering our world’s current situation, we need all the help we can get to start asking different kinds of questions and exploring new pathways where old ones are failing. That is precisely where the power of human-machine interaction lies.

Our Beethoven AI gave us options, options we could never have produced without it in such a timeframe. In so doing, it maximised our creativity. The options it so effortlessly produced were threefold. First, they expanded our horizons in that AI didn’t care about our conventions, taboos, or rules. Second, they gave us freedom, putting us in the driver’s seat with an amazing array of choices.

Finally, they saved us tons of time which we could spend focusing on and learning about things that really matter. All of that is indeed “human” music to our ears.

If an AI can help humans be more creative—more “human” even—the question remains: Why are we not employing this technology much more widely to address and solve other problems too?Perhaps the answer is that our age lacks courage. Business-as-usual mentality and fearing failure is omnipresent in our organisations. Many are reluctant to experiment with AI within the context of creativity. Or maybe the fear lies in the idea of a machine becoming a “more creative individual” than us, as if we were in competition.

Humans are not computers, nor should they be treated as such. Unfortunately, this is still the case: just look at your child’s homework sheet, and you’ll immediately know what we’re talking about. Our systems should be focusing more on raising first-class creative and collaborative thinkers, learners and inventors, rather than programming what are essentially second-class calculators.

Picture left: Copyright Deutsche Telekom / Norbert Ittermann

Let’s accept the reality: Humans are generally not very good at reproducing Knowledge 101. Our memory capabilities and speed of data-processing are simply flawed in comparison with machines. But we excel at other things, particularly at empathy and creativity. We are also extremely good at unleashing the potential of all sorts of tools around us: We invent tools to improve the lives of people we’ve never even met. We utilise tools all the time to inspire and connect with each other. Our Beethoven AI is one of them.

This is a turning point in history. Instead of asking whether someone is “allowed” to use AI in the creative process or to emulate the style

of a creative superstar, we should be instilling the right mindset and the joy of experimentation to awaken the creative superstar inherent in everyone. It is high time we stop putting people into boxes only to later instruct them to think outside of the box!

As the debates and reflections around our Beethoven experiment unfold, we must begin acting on that promise.

Our world is slowly coming out of the Industrial Age, but what’s next is not the age of technology, digitalisation, or transhumanism.

It’s the Age of Creativity!

Matthias Röder

Dr. Matthias Röder is an award-winning music and technology strategist. He is Co-Founder and Managing Partner at The Mindshift, a consultancy on creative leadership and innovation strategy. Matthias currently serves as a board member of the Karajan Foundation and is the Managing Director of the Eliette and Herbert von Karajan Institute. He is also a member of the board of trustees of the Mozarteum Foundation. In 2017, Matthias founded the Karajan Music Tech Conference, a cross-industry event to promote breakthrough technologies in music, media and audio. He is also the founder of the Classical Music Hack Day series which he launched in 2013. Together with his wife, Seda Röder, Matthias co-founded the Sonophilia Foundation, a non-profit that promotes a scientific approach to creativity. Matthias has won numerous prizes and accolades for his work, including most recently, the “Game Changer” Award of the Chamber of Commerce Salzburg. He is a sought-after speaker and lecturer who has taught at Harvard University, the Change & Innovation Management Program at University of St. Gall, and Salzburg University. He holds a PhD in music from Harvard University and is an alumnus of the Mozarteum University Salzburg.

Picture © HUBERT AUER Salzburg

Seda Röder

Seda Röder, aka “the piano hacker”, is an author, entrepreneur and philanthropist devoted to cultivating creativity in society and organisations. She is a sought-after speaker, consultant to DAX listed companies and the founder of the Sonophilia Foundation; a non-profit organization dedicated to advancing the scientific research of creativity and critical thinking. Seda is Co-Founder and Managing Partner at The Mindshift, a consultancy on creative technologies and change leadership. Furthermore, Seda is a fellow and a member of the Salzburg Global Seminar Corporate Governance Forum, angel investor and network partner at the European startup accelerator Silicon Castles. In 2018 Seda received the Game Changer Award at the Austrian Chamber of Commerce for her business merits. Before relocating to Europe, Seda taught music performance, theory and history at Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) as an Associate and Affiliated Artist.

Picture © Private Collection

Intro: The Next Renaissance is a Renaissance of the Next

Lead of The Next Renaissance Project & Director of the European Creative Business Network (ECBN)

Are we the chicken or the egg?

The next and new is happening daily—in the digital world even every second—as viewers of next developments are also senders turning the next to potential news for others. One click to RT: New-ism meets Instant-ism. So is there really any room for a Renaissance, any chance to even realise the next new dimension in societies´ evolution, before it is surpassed by the next tweet, taking 100 of millions in elevators of soaring hopes or self-enhancing frustration? This is why the movement to think more slowly, more deeply and more from a 360° perspective is gaining traction.

There truly seems no shortage of the next big trend or of moon shot innovations. But there’s no shortage of crises either, from the next pandemic to the next hunger and housing crises, real estate and banking crises, mobility and climate crises. To our societies, crises are intermediate states on the way to their success, the necessary evil, for some even—as in economy—the prerequisite for recovery. This crisis concept is a pact for the wealth promise of societies after World War Two—and its social cohesion and peace.

But if crises become ever faster and ever longer, if recovery periods become shorter or are omitted, then the grand narrative of our society is less and less sustainable: “The Next Big Thing“ is longer the next thing to hope for or to expect. And even more: The belief in “Real Next“ is challenged by the relentless ticker tape of daily updates, breaking news and constant social media notifications popping up. It might be no accident that just in this setting more and more citizens believe that their children will not live a better life than their own—despite the fact that this generation has accumulated an unprecedented amount of wealth and health.

The Next?

“It is hard to see a way to a golden age, especially since we know we need to shift our economic order and a way of life that is materially expansive, socially divisive and environmentally hostile. And doing that cannot be grasped by a business-as-usual approach as it takes a while for new ethical stances and new ways of operating to take root and to establish a new and coherent world view.“1

The impression of missing out on the next is re-enforced by the ever-growing need for the next big transformations to tackle climate change and save the planet from overheating. For 30 years now, transformation toward a sustainable society has been debated in professional circles and while a bundle of theories emerged how to change complex systems in a wicked crisis—from Uwe Scheidewind’s Zukunftskunst to Mariana Mazzucato’s Mission Economy—societies at large are unwilling or reluctant to embrace change, especially quick change, without guarantees about being on the winning side after such change. Even with the emergence of activist groups like Fridays For Future—the youth-led global climate crisis strike movement—and declarations of a climate crisis in many cities, speedy realisation in societal change is not widespread. It is five minutes to midnight and still the “Next” seems to remain a grim inevitability rather than a cheerful freedom.

But what if the “Next“ is something different?

What if… generating the next generation of talents, jobs, housing, cities and streets, growth and wealth in the current system of doing the next thing no longer works given the current paradox of a raging standstill?

What if… for change of the societal pact and its structures to happen, understanding and researching the “next” as a process for the systemic “next” is necessary?

What if… the “next” is an innovative method of change-making?

The Next Renaissance!

The “next” in the 2020s must be a novel system which is able to produce the next generation of talents, jobs, housing, cities and streets, growth and wealth—and a radically different societal pact.

The World Economic Forum just published for the Davos Agenda 2022 a proposal for a radically different pact of state and business. “That redesign of all the different levers that the state has—from procurement, grants, loans, bringing in conditionality to have a proper symbiotic social contract, and more—is much harder than just talking about it… That requires a very different type of public-private partnership,” as Professor Mariana Mazzucato explains.2 in other words, a new social contract is needed. Klaus Schwab, Founder of WEG, and Thierry Malleret call for a new Great Narrative.

C40, a union of 97 cities representing 25% of the global economy, implements the “Race to Zero” global campaign for cities to “immediately proceed“ with carbon reducing projects.3

The UNESCO Creative Network pushes for a new cultural contract in society wherein the public sphere is approached “with a new perspective that public authorities, in cooperation with the private sector and civil society, can make the difference and support a more sustainable urban development suited to the practical needs of the local population.”4

In addition, industries can promote new ways of making the radical “next”—or “innovation“, as industry might call it. For example, even Digital Europe claims “creating digital inclusion and green growth.“5

Innovators from the arts, culture and creative industries of today are also contributing to a transformative re-design of societal systems by radical different collaborations of arts, technology, business and society creating new values — this is what we call the Next Renaissance.

It is all transformative

The world stands at the cusp of a critical moment. Our crises, often dark and gloomy, can be opportunities and can provide gateways from one world to the next as new agendas come together in unprecedented ways. There is a mood and a movement emerging. We are seeing the possibility of creating a different world driven by other principles. It is a compelling story. Think eco-principles and the green transition, the circular economy, new concepts like resilience, co-creation and the participatory imperative—and let’s not forget a digitising world that allows the cultural and creative economy to run through systems like electricity in its inventiveness. Together it is all-transformative.

“It is a compelling story. Think how eco-principles are beginning to shape our mindset and how that provides the frame and therefore courage to move towards a green transition where the circular economy notion plays a crucial part. Think too how newer concepts like resilience help us work through the tasks ahead or how co-creation and the participatory imperative helps harness the collective imagination (since transformation is a collective endeavour). Think here too of the notion that the world is our commons. And not to forget a digitising world that allows, in particular, the cultural creative economy to run through systems like electricity in its inventiveness and with its immersive capacities. Sometimes the speed of the possibilities are dizzying and we always must be alert that we, rather than the technologies, are in control.”6

The Green Transformation “is not just an environmental or economic project: it needs to be a new cultural project for Europe,“ as EU President Ursula von der Leyen pointed out 2021.7 And so started the lead initiative in Europe raising hopes for the Next Renaissance to really happen. But—it should be added—this will not happen without a Cultural Transformation, without a radically different pact of the arts, culture and creative industries with society.

Re-Designing Systems

Our contribution to this Next Renaissance takes a closer look at examples of re-designing the systems of arts, culture and creative industries just as arts, culture and creative industries are re-designing systems of industries and markets, of cities and regions or of technologies and societal changes. And let’s not forget how the arts and culture re-design technologies.

In 1435 “Alberti published the treatise On Painting, leading to inventors using the camera obscura to automate perspectival drawing, and, within decades, Louis Daguerre and William Henry Fox Talbot industrialised it by inventing photography.“8 The iPhone took photography to a final stage of everyday use and empowered potentially everyone to be an innovator, to have a new take on and picture of the world! “Did Alberti imagine streaming media when he wrote On Painting? Imagine the value unleashed by 21st-century infrastructure of media—from streaming to 3D—which supports decades, even centuries, of progress.”9

While this book takes a closer look at examples of re-designing the systems of arts, culture and creative industries, it is not devoted to a historical analysis or even a language-sensitive analysis of historical Renaissance. While some authors here find analogies between the present-day and previous Renaissances, we did not look into the social settings of these times. Instead, this book works with an image, a perception of the historical Renaissance—but this picture does not necessarily resemble more rigorously historical representations of those earlier Renaissances that we get from scholars of the subject. For example, the word “art“ was not used in Renaissance times as we understand that term today. In fact, Science and Art were not distinguished as separate fields in the historical Renaissance as they are today.

Rethought Principles

So we must be strict and clarify a rule: Talking of a Renaissance today does not give us any vocabulary or even an understanding with which to discuss the historical Renaissance. Nevertheless, we are able to develop our own fiction of a future—even if it is built on a fiction of historical truth.

However, the creative economy also redesigns attitudes, behaviours and values: “A changed mindset, rethought principles, new ways of understanding and generating ideas are the cornerstones of change.” 10 After a first rush of technological solutions for a resilient society—the early (almost naïve) Smart City Movement—it is now common sense that without citizen engagement and their adaption of new values and behaviours a resilient society will not succeed.

“The Next Renaissance”’ is a collection of diverging perspectives which are nevertheless all united in one purpose: to thrive and unite through the diversity of creativity and culture for a new social system of changes which is as inclusive as possible—though which in addition takes the uncomfortable beyond the horizon into account. Of course, debating the Next Renaissance is an ongoing, inherently incomplete and—if you like—systematically a-rational undertaking; still it is unavoidably necessary. In the diversity of contributions we received, we discovered common threads for a system re-design—and we might discover other threads as well.

We decided to share these joint “rethought principles” and cluster the book accordingly, taking it as an opportunity to overcome the idea that a system re-design for an inclusive transformation towards a resilient society can be built on sectorial clusters—on a 19th-century thought model of excluding professions from value chains by defining artificial sectorial borders.

Appraisal, not Praise

This book is published in a time of “constant lip service to Renaissance that is so much characteristic of our times. The self-made digital economy tycoons like Steve Jobs, Sergey Brin and Larry Page, or Elon Musk are celebrated as the contemporary equivalents of the Renaissance man…Samuel Beckett’s ‘Fail again. Fail better’ quote has become the most famous inspirational quote of Silicon Valley culture.”11

We must aim not for praise, but for appraisal, a critical assessment of the European role in a global re-design12 and self-reflections. Still, we must not lose sight of the unique capacity of culture, as Geoff Mulgan says, “the imaginative space that is so badly needed now… That may also prompt [them] to work harder to be part of the solutions rather than part of the problem and to help us to be actors not just observers.”13

Time is short to make the big difference and driving this change are many—politicians, activists, civil society, researchers, inventors, artists, entrepreneurs, business, writers and more. We need to harness their collective talents, will, energy, intelligence and resources to create a more human-centred world based on one-planet living.

Innovators in the creative economy—at least all the contributors in this publication—share the commitment and the belief that the Next Renaissance is empowering citizens to be more creative in shaping their own future. In a nutshell: Now is the time to act and to turn ideas into reality.

No chickening out.

Sources

1 Charles Landry

2 https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/01/mariana-mazzucato-on-rethinking-the-state/

3 https://www.c40.org/what-we-do/building-a-movement/cities-race-to-zero/

4 https://en.unesco.org/creative-cities/content/why-creativity-why-cities

5 https://www.digitaleurope.org/about-us/

6 Charles Landry

7 von der Leyen, https://europa.eu/new-european-bauhaus/index_en

8 Ali Hossaini

9 Ali Hossaini

10 Charles Landry

11 Pier Luigi Sacco

12 Johannes Ebert

13 Geoff Mulgan

Bernd Fesel

Initiator & Lead of The Next Renaissance Project and Managing Director European Creative Business Network

Mr. Fesel has experience in CCSI for over 30 years and is currently the director of the European Creative Business Network (ECBN), a not-for-profit organization of over 170 members from 44 countries that supports and develops the cultural and creative industries in Europe. Prior to this role, he was a serial entrepreneur within the CCSI sector, held the role of vice director of the European Capital of Culture in the Ruhr Region and was senior advisor to the legacy institute of RUHR.2010 til 2018: the european centre for creative economy in Dortmund. He played a key role in EU initiatives such as like JRC-Creative City Monitor, Voices for Culture program and ENTACT and setup a European Research Alliance on Spillover-Effects of Culture and Creativity. Since 1990 Bernd is founder of startups, architect of novel public organisations, inspirator for programs and policies for CCSI, friend and connector of acclaimed artists as well as influencer and publisher. Also he was appointed adjunct professor at the Caspar-David-Friedrich-Institut in Greifswald.

The future belongs to the creative

Hamburg Kreativ Gesellschaft

The future belongs to the creative

How companies use the potential of the creative industries to stay innovative

Tesla is not a car manufacturer. Tesla is a software company that also makes cars. The car is one product of many, limits are not set. Tesla founder Elon Musk always thinks in terms of opportunities and possibilities, but never in terms of traditions. And that’s new. These are new realities of life that now pose major challenges for numerous companies, especially when it comes to developing innovations. Because tomorrow’s innovations are at odds with today’s industries. In this piece Hamburg Kreativ Gesellschaft mbH shows how looking into the future of content and creative industries is a tool to improve innovation today—across all industries.

The automotive industry is currently experiencing new realities very accutely, especially as it is in the midst of the biggest transformation process in its history. If we leave aside the most obvious challenge—namely the technical component—from the combustion engine to the emission-free automobile, we see a development whose dimensions should not be underestimated: User behaviour is changing dramatically. Not everyone wants their own car and car-sharing is becoming more and more common. In addition, there is a growing environmental awareness, but also social areas of conflict (for example, available and affordable housing) are displacing the supposed self-evidence of owning a car.

Picture above: Welcome at Play Day Final, Copyright by Laura Müller

Picture left: Demo Prototype, Copyright by Laura Müller

The image of the future

The new mobility—especially in large cities—is creating an acute need for innovation in the industry far beyond the ecological-technological sphere. Thus, data- and content-based business models are becoming a central component of a sustainable business model. For the automotive industry (as for many other industries), it will also be a matter of crossing previous industry boundaries and working in an interdisciplinary manner in order to remain capable of innovation. Above all, however, companies will have to deal more and more intensively with the future. We often still cling to the idea that we can’t determine the future, but that it will be determined. But that may prove to be a mistake. Instead, we will have to create tools and methods to really look ahead. Only in this way will the picture emerge toward which we must work.

In 2019, nextMedia.Hamburg and the Cross Innovation Hub (part of Hamburg Kreativ Gesellschaft mbH) developed Content Foresight, a unique, Europe-wide tool for bringing together different perspectives, different know-how, different inspirations, and also very different creative approaches in a media- and technology-diffuse world. Content Foresight has since proven to be a highly effective method for making reliable predictions for the content industry based on creative input and interdisciplinary collaboration with other industries. Just one example: If autonomous driving becomes established in the medium term, mobility providers in particular will have to become much more involved in other business areas than before. Because when the car drives itself, drivers will have time and space for new forms of occupation, new forms of media use. This, in turn, requires creative and content-related input, i.e., content! And that promises enormous potential for creative and media professionals.

Content Foresight promotes creative innovation work

The Content Foresight innovation program we developed is a tool for testing new applications and future business areas for the content and media industry. Content Foresight is based on the research-proven methods of Strategic Foresight and was adapted and further developed by us for the content industry. Beyond the productive interdisciplinary setting, Content Foresight thrives on impulses, ways of thinking and specific skills of external creative professionals who are included in the innovation process. These professionals come from the different submarkets of the creative industries to form a so-called „pool of creatives“. As part of the project, they are not only paid for their contributions, but also meet the participating companies at eye level and can build a new network. Applicants so far have been people from the various submarkets of the creative industries, with a focus on different digital competencies, i.e. software development, PC games, interaction/UX design, sound, virtual and augmented reality and storytelling.

The new renaissance of the creative

The „New Renaissance“ that is emerging now, at the beginning of the 21st century, will have to leave behind the purely growth-oriented, resource-consuming innovations and thus bring about socially desirable changes. The term Renaissance was chosen deliberately because the „old“ Renaissance, i.e. the period between the 14th and 16th centuries, led to a boost in innovation in various areas; it was the time when technology and art, science and creativity merged. We want to build on this—especially in times of the COVID-19 pandemic—in order to contribute to overcoming the crises of our time. Because it is a sector that we hold in high esteem which is becoming the driving force behind this movement: the creative industries. It seems to be the sustainable winner in the merging of all areas of our lives. It is characteristic of the new renaissance that problems and crises can be solved more and more effectively across all areas and sectors. What was once separate, the creative person is able to connect with bridges and lead to innovative solutions. The creative industries are now an innovation-driving sector of the economy that is successfully leading other economic players into the new renaissance.

Picture left: Foresight Process / Copyright: Rohrbeck Heger GmbH

In recent years, the content-producing players in the creative industries—the publishing, media and music sectors, and of course journalism—have been the first sectors to digitise and transform themselves and they continue to do so. This is because the traditional media companies are facing a permanent change in terms of the behaviour and demands of the users of their products and services. Subscriptions are becoming memberships, content providers are becoming curators, and monothematic offerings are becoming lifeworlds and services that must be able to be mapped seamlessly on all platforms. As a result, data-driven business models are moving further into the foreground. Diversified business models must be found to suit the sovereignty, flexibility, and individuality of these users. With the credo of „meeting users where they are“, the industry has had a self-imposed target since the 2010s and continues to be dependent on technology and data, and thus on monopoly-like infrastructure providers, such as platforms, software and hardware providers. One also observes within the content industry an increasing merger of different providers into cooperations, alliances or mergers—and with it an increasing willingness to innovate, indeed an innovative power.

In other words, the content industry has the best prerequisites for the new renaissance.

Picture right: Status Quo, Copyright by Laura Müller

Looking to the future promotes the innovative power of today

In our view, Strategic Foresight is therefore the most suitable method for bringing together areas that are supposedly alien to one another to exchange ideas and find concrete solutions to their current and future challenges. After all, looking into the future promotes innovation today. However, companies still too often face major hurdles in perceiving and exploiting this potential. But simply dealing with a time horizon of five years is still unusual in companies. In order to better cope with the approaching, rapid changes and not only remain capable of acting, but also to be able to shape the future, even more courage and willingness to take risks will be required in the future.

This willingness also includes cooperation across industry and company boundaries. Most industries and management strategies still seem to be unfamiliar with open and cross-innovation processes. Yet the increasing complexity of our world is due not least to the convergence of markets and industries. So while classic competitive thinking can make long-term innovation even more difficult, it is often neutral and supra-organisational approaches that can create new spaces of opportunity and change mindsets. And above all, the involvement of the creative industries creates additional potential. Their ways of thinking and working not only provide new impetus for the innovation process itself, but are also becoming indispensable in view of the need to shape a new, sustainable, equitable future.

Picture below: Michail Paweletz reads 2034, Copyright: Laura Müller

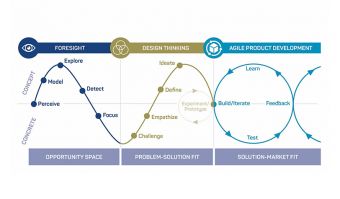

For the practical application of content foresight, we rely on the following approaches:

1. With a cross-innovation approach, we create a setting that is considered to be particularly conducive to innovation and can thus bring two different sectors into innovation work in a targeted manner, in which we work in a user- and solution-oriented manner with the help of methodologically sound processes.

2. The focus is on methods of strategic foresight, which not only look at the development of possible futures, but also specifically enable the identification of so-called opportunity spaces and thus recommendations for action to successfully anticipate them.

3. In the subsequent design thinking process, concrete prototypes are developed alongside the joint visions. In addition, we rely on special impulses in these processes through targeted collaboration with actors from the creative industries.

4. As a public provider, we also act as a neutral player in this process and create trust among the companies involved and, where applicable, among competing companies.

With this setting, in a format that is unique in Europe, we are not only creating an experimental area for concrete approaches to current and future challenges, but also new impulses and foundations for the sustainable innovative capacity of the participating players.

So what do the possible futures look like when actors from the content industry work together with mobility experts? Where are the opportunity spaces? Content Foresight – Mobility by nextMedia.Hamburg and the Cross Innovation Hub produced the following triad of innovations:

Business ideas using the example of the content & mobility interface

I.

2024. For a time horizon of five years, the Hamburger Morgenpost and Schwan Communications have developed a tangible solution for linking content and mobility offers that can already be implemented with current technologies. The prototype Digital Guided Tour /HAM offers users multimedia content (video, audio, text) that functions in a wide variety of means of transportation, is coupled with them, and whose playout is adapted to the means of transportation. In this way, it not only offers content providers new distribution channels, but also creates incentives for the use of public and/or climate-friendly means of transport in the city—from e-scooters to sharing offers and public transport. This applies not only to local residents, but also to the more than seven million tourists who visit the Hanseatic city every year, thanks to the integration of tourist attractions and historical content.

II.

2029. The project team of MaibornWolff and pilot Hamburg planned the next step: With S.T.E.P—the Seamless Travel Experience Platform—mobility and entertainment/information are individually tailored to the user. Instead of having to actively choose from countless options how to get from A to B and which content can be consumed on the way, a digital twin creates situationally optimal decision bases for seamless travel planning. The blockchain-based application already developed promises all-in-one processing. In a planning horizon of about five to 10 years, app chaos on smartphones will then be as much a thing of the past as login madness. Through a public-private ownership model, in which the public sector acts as a regulator, a critical mass of services and users* can be aggregated, which can fully keep an eye on the optimisation of passenger transport, independent of the economic success of individual providers.

III.

2034. What’s next? How do we envision mobility and content when blockchain technologies and AI-supported systems have long since become part of our everyday lives and our data precedes our decisions? Representatives from NDR, Axel Springer, HOCHBAHN, IAV, ITS Hamburg 2021 and Wunder Mobility give us an impression of this in their concept of experiential mobility. In the sense of a pre-prototype, the team developed a vision of mobility in a time horizon of about 15 years, which considers social (e.g. environmental protection, education), political (e.g. data sovereignty), technological (e.g. autonomous driving, artificial intelligence as technology serving people, digital identity) and individual aspects (e.g. consumption, convenience) in equal measure and integrates them into product and service scenarios.

The vision, spoken by ARD news anchor Michail Paweletz, is publicly available here.

Open even to unfamiliar input

So… You can’t do it without looking into the future. But… Everyone looks at the future differently. To find the best solution together, it is crucial to organise an exchange—and to learn from each other. This is the only way to create innovations.

If you want to be innovative tomorrow, you have to be open today, even for unusual input—and above all for new content!

Quotes from company representatives:

Dr. Johanna Leuschen, Head of NDR Audio Lab (Norddeutscher Rundfunk)

„We believe that in the future we will always get the content that is best suited to our mood, in the current mobility situation, in the time available. The keyword here is personalisation. The user focus is and will remain essential. For journalism, AI could be useful in an assisting role: Tasks that do not necessarily require creativity (weather, election or sports results) could be taken over by algorithms. Then journalists could devote themselves entirely to creative and research-intensive topics. And we assume that companies in general, not just content providers, should look at an audio and voice strategy and tailor their offerings for a voice-driven world in the long term. Discoverability is going to be a big challenge going forward.“

Nicolas Meibohm, Head of Connected Car (Axel Springer SE)

„We often still cling to the idea that we can’t determine the future, it will be determined. But that is exactly the mistake. So now, once we really look ahead, we get a picture we can work toward. This program has set a benchmark and proven that interdisciplinary collaboration really makes sense.“

Hendrik Menz, ehemals Director Business Development (pilot Screentime GmbH)

„It takes a wide range of relevant expertise and value-added fields to absorb the necessary complexity of a holistic approach.“

Dr.Nina Klaß

Dr. Nina Klaß is an expert in content and tech innovation. She leads nextMedia.Hamburg (part of Hamburg Kreativ Gesellschaft mbH) where she developed and executed a range of highly recognized innovation programs such as the Content Foresight project. Previously, she was head of digital product marketing & sales management at SPIEGEL Group. She is active as funding committee member, jury and advisor of innovation programs worldwide.

Picture © Oliver Reetz

Egbert Rühl

Egbert Rühl has been active as a cultural and arts facilitator his whole life – in many different genres and functions. He is the managing director of the Hamburg Kreativ Gesellschaft. In this role, he is responsible for strategy and tactics, guidance and moderation, budget compliance, and contact with politics and administration.

Picture © Oliver Reetz

Marc Eppler

Marc Eppler is responsible for nextMedia.Hamburg’s partner management and he operates programs such as Content Foresight. Previously, he worked at the Franco-German culture channel ARTE in Strasbourg.

Picture © Oliver Reetz

Stranger To The Trees

Artist in Residence at the Faculty of Maths and Physical Sciences, University College London & Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts

STranger to the trees

Hybrid art uncovering a new materiality in our world, for crisis or awakening…

The Green Transition of our society is urgent and will drive the renewal of cities and economy alike, as we overcome the Covid-19 pandemic. However, to move beyond our current relationship with what is casually called “the environment”, we must in fact reconfigure the understanding of humankind’s influence on the planet.

Stranger To The Trees (STTT) is a transdisciplinary art-led project that sheds light through a hybrid artistic form on the invisible but harsh reality of how microplastics are changing the materiality of the world. The work steps outside of the human perspective by focussing on the possibility of coexistence between microplastics and trees. In so doing, the work addresses a fundamental necessity—that of moving beyond a human-centric view to achieve a more-than-human understanding of the echoes of human activity.

STTT is a multimedia, interactive installation that combines sound, sculpture and video, alongside a scientific publication (Austen, 2022). A combination of these forms of output sheds light conceptually, factually and emotionally on the possibilities and meanings of microplastics and birch trees coexisting in the time of the climate crisis.

Microplastics are a ubiquitous and irrevocable anthropogenic new material dispersed throughout the environment reaching the furthest and wildest crannies of the planet. Particles of plastic have been found in the clouds, on top of the tallest mountains and in the deepest ocean trenches. This artificial material represents the uncompromising impact of human activity on the planet and has already been observed to be an evolutionary prompt for microorganisms. Furthermore, microplastics’ presence is an embodiment of our addiction to the extraction of fossil fuels, or as they should properly be named, long carbon reserves.

We cannot call back these tiny fractionations of humanity’s exploitative industrial legacy. They persist even beyond our reaches, changing the materiality of the world and the entities within it, even ourselves. What we can do is to reconfigure our understanding of the consequences of this undeniable reality. The artwork Stranger to the Trees addresses this issue through the lens of coexistence. The work realises in hybrid artistic form the new materiality of the entanglement of forests and plastic pollution.

The project was driven by a motivation to understand the stark reality of microplastic pollution from a more-than-human perspective. Central to the concept is the fact that plastic pollution is, like forests, itself a carbon sink. In the context of fossil fuel extraction and the carbon cycle, the question arises of whether microplastic interaction with trees might, beyond the instinctive horror of artifice pervading nature, carry another meaning. The research for the project, which is still ongoing in the form of a long-term experiment, mixes artistic and scientific methods to explore how birch, a pioneer tree species, and microplastic particles interact.

Stranger to the Trees successfully melds DIY and traditional scientific research with artistic research and production. The diverse outputs, each impactful in its own way, together provide access to a new understanding of what we perceive as nature. The project showcases a modality by which to develop the aesthetic, cognitive and embodied knowledge needed in order to move towards a more just, resilient future in which humans cooperate with those entities with which we share the planet.

References

Austen, K, Maclean, J, Balanzategui, D and Hölker, F, “Microplastic inclusion in birch tree roots”, Science of the Total Environment, 808 (2022) 152085 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152085

More info: https://www.katausten.com/portfolio/stranger-to-the-trees/

Other partners involved (think of artists/ producers/ industry/ science collaborators): STTT is realised within the framework of the European Media Art Platforms EMARE program at WRO Art Center with support of the Creative Europe Culture Programme of the European Union

All Photos: Copyright by Andreas Baudisch

Kat Austen

Kat Austen is a person. In her artistic practice, she focusses on environ-mental issues. She melds disciplines and media, creating sculptural and new media installations, performances and participatory work. Austen’s practice is underpinned by extensive research and theory, and driven by a motivation to explore how to move towards a more socially and environmentally just future. Working from her studio in Berlin, Austen is currently Artist in Residence at the Faculty of Maths and Physical Sciences, University College London, Senior Teaching Fellow at UCL Arts and Sciences and Associate Artist Fellow at Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies, Potsdam. Her studio hosts two Scientists in Residence through the STUDIOTOPIA programme hosted by Ars Electronica. She is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts. Austen was Artist in the Arctic 2017 for Friends of Scott Polar Research Institute (University of Cambridge) for her project The Matter of the Soul. In 2018 Austen was selected as inaugural Cultural Fellow in Art and Science at the Cultural Institute, University of Leeds for the same project. Austen has been awarded residencies internationally, including EMAP / EMARE Artist in Residence at WRO Art Center, AiR at NYU Shanghai, ArtOxygen Mumbai and LAStheatre.

Picture: © Andreas Baudisch

Beyond Instrumentalism

Director of Creative Industries Policy & Evidence Centre at Nesta & Fellow on Art and Society, Metcalf Foundation

Beyond Instrumentalism: The Aestheticisation of the World

Climate change? Global pandemic? Collapsing biodiversity? Distressed migration? Spiralling inequality? Cutting across many of the urgencies facing humanity is a growing epistemic crisis, a widening gap between our knowledge paradigm and the problems of our day. One surprising response to this growing epistemic crisis, as the contributions in this volume illustrate, is the corresponding turn to art, not as entertainment or distraction, but as problem-solver. While this appears to be largely instinctive—a collective intuition ungrounded by conceptual or methodological clarity—it deserves investigation.

The Crisis of Knowing in the Age of Complexity

How did our problems and our problem-solving get so disconnected? During its rise to prominence, Western, Enlightenment rationality systematically divested itself of subjectivity in order to see the world objectively. Human values, perspectives, and beliefs were dismissed in pursuit of irrefutable facts. The complicated world has become the complex world and with a knowledge paradigm built for the former, we find ourselves, to use a recent metaphor, trying to play three-dimensional chess on a two-dimensional board. Our missing dimension often goes by the name ‘the normative’, indicating elements of identity, meaning, purpose, belief, senses of time and place, and the underlying ontologies shaping our conceptions of the world and ourselves within it. We see this in the declining capacities of our R&D paradigm, privileging science and technology and rendering contributions from the arts, humanities and social sciences illegitimate. The R&D paradigm is built for the problems of two-dimensional chess, but the crises that define our age cannot be resolved in two dimensions alone. Can knowledge creation which enriches our understanding of, and engagement with, these irreducible uncertainties, be of greater societal value in the Anthropocene?1

Art as Magic Bullet

Complexity features an entanglement of normative or human dimensions shaping the problems we are hoping to solve within a paradigm built to ignore those exact dimensions—leading much of the early 21st century on something of a fool’s errand. Yet why the turn to art? Might it weave human values, perspectives, beliefs, and activities back into how we make sense of the world, thereby allowing us to navigate—and manage—our normative entanglements more effectively? Is it, in other words, a means of shifting from the complicated to the complex by adding a third dimension to our chessboard?

From Plato’s suspicion of poets, to church and state controlling art’s expressive range, or Soviet Socialism’s faith in artists as “engineers of the human soul”, and climate activist Bill McKibben crying out “what the warming world needs now is art, sweet art,”2 the idea that art shapes worlds transcends history and ideology. These perspectives share neither politics, epistemology, nor cosmology. Where art happens, faith in its world-making power grows. We turn to art to shape our societies based on a tacit recognition of how art has shaped us, revealing both the durability and vulnerability of art’s relationship to social impact,3 from “did do for me” to “will do for others.” Herein lies the risk of instrumentalising art; often, our enthusiasm for art finds us trying to replicate effects rather than processes. In trying to replicate what art does rather than how art works we jeopardise the means by which art engages life in aesthetic terms, often disenchanting the very power for which its help was sought in the first place. These dichotomies—effects vs processes; what art does vs how art works—are not meant to dim our hopes to apply art to social challenges, but to distinguish between art as a descriptive capacity versus an epistemic capacity. If art is to expand our proverbial chessboard by shifting how we know the world beyond two-dimensional Western objectivity, it must recognise an often invisible fork in the road. Down one path, art forms a tool to serve our two-dimensional, complicated world; down the other, something potentially more transformative awaits. The latter invites the aestheticisation of the world, a reopening of that once-maligned plane of engagement we tried to close over the course of the Enlightenment.

Art as Method

This growing intuition that art offers unrealised capacity to contribute to our growing epistemic crisis deserves enthusiasm. Coordinating the energy and reach of our cultural sectors while bringing them into more applied relationships to societal challenges could prove transformative. Yet such a vision implies an art-society relationship that is necessarily paradoxical—applied yet not instrumentalised, enfranchised yet not autonomous. One approach to this paradox is through a relationship between art and R&D. Historically, these fields dislike each other; art is too impulsive for R&D’s ‘systematic’ approach to knowledge creation, and R&D too reductive to admit the imaginative range of arts practices.4 Yet as art faces a destiny where it is more applied and accountable to its larger impacts, and R&D struggles with the normative dimensions of contemporary challenges, they may not be such odd bedfellows as they seem.

In terms of its value proposition, we often say art is a way of ‘seeing differently’, yet without specifying how, we jeopardise the capacity, while yielding little methodological clarity to contexts of application. Typically, art is considered a power of expression, the sounds, imagery, words, and movements it makes, often leading to its hasty use as a tool for making statements. Yet within this power of expression lies an equally important power of attention. Art is the capacity to attend to the world in terms of the aesthetic; perhaps more than its expressive power, it is perceiving via creative practice that generates such unique value. Consider this within the recursive relationship between mind and world, where mentality produces society, and society produces mentality. Such a dynamic is built for getting stuck. Agency, inspiration, reflexivity and creativity are constrained by design, and design is constrained by agency. Art as a power of attention, a means to engage the world less hampered by this recursive dynamic, offers a unique value that might make the arts vital to innovation. Rendering this explicit articulates a value proposition we can use to operationalise art in service of our worlds while protecting it from being reduced to a charismatic mouthpiece—that ‘power of expression’ alone.

Framing problems in terms of aesthetics is essential to effective applications of arts practices. How do we spot the arts-shaped holes in our world? Here we begin to shape that third dimension on our chess board. Often, we equate the normative with matters of taste and opinion, luring us into thinking that information, data, facts and reason might inspire the reflexivity societal problems like climate change, pandemics, and social and economic justice require. As is far too abundantly evident, divisive dialogue and increasing polarisation are the results of this misconception. Fostering reflexivity, agency, and change at the normative level—that is, navigating that third dimension of our chessboard—requires fashioning carefully constructed passageways that lead from one world to another. Consider how many of us are eager to depart toxic capitalism. Bringing such hope into an applied and accountable relationship with society requires careful consideration of method and evaluation. Clearer problem statements enable more specific questions of artistic method—e.g. what processes engage the problem? And how will stakeholders be involved? In terms of evaluation, words like ‘data’ and ‘assessment’ sound threatening to artists. With clear problem statements and corresponding methods established by the artistic process, can we reconcile the accountabilities of others with our own? In other words, what value does the artistic process seek to produce? Where was this contribution realised or not? What data do we need in order to know? And what processes will be used to interpret and integrate that data in decision-making? This more empowered relationship to assessment allows applied artistic processes to serve more accountable roles in society without trying to prove themselves on foreign terms.

Policy for Playing Three-dimensional Chess

Our core suggestion is that within a much-needed expansion of the R&D paradigm, art might contribute its unique epistemic value to the growing epistemic crisis.

The starting point is to reflect the arts’ distinctive contribution to R&D in the international bible for R&D policymakers, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Frascati Manual: Guidelines for Collecting and Reporting Data on Research and Experimental Development. Now in its seventh edition, the Manual is used by policymakers, statisticians, academics, and others, to help standardise the data collection guidelines and classifications for compiling R&D statistics. In successive revisions, the Frascati Manual has evolved to recognise arts R&D, but it has done so by shoehorning art into scientific understandings rather than extending its own definitions and parameters, e.g., referring to “observable facts” and “knowledge of the underlying foundations of phenomena” not to behaviours, and to “systematic work… directed to producing new products or processes” not to human experiences. Elsewhere in the Manual it is made clear that R&D must aim to resolve scientific and technological uncertainty. It is of fundamental importance that the Frascati Manual and the R&D definitions within it are made fit for purpose for the complexity economy.5

National statisticians in turn must adapt their measurement activities to measure R&D so defined.6 The basics of an approach are already in place with the OECD’s Fields of Research and Development (FORD) classification. Statisticians can use this classification in their R&D surveys to measure R&D expenditure and personnel by fields of enquiry—in other words, broad knowledge domains including the arts–based on the content of the R&D subject matter. Survey returns on R&D spending by FORD are only as good as the accounting data that organisations collect, however, so national statistical institutes need to engage with businesses, public bodies and charities to ensure they too are adapting their R&D measurement systems accordingly.

Armed with more inclusive definitions and metrics, governments can then ensure their R&D strategies, subsidies and tax incentives are fit for purpose too. They can fashion interventions that are designed to fully avail society of the R&D potential of the arts. What, for example, would the missions’ turn in innovation policy look like if artists participated in the setting of grand challenges, foresight exercises, policy design and planning? How would skills and policies for the knowledge economy change if they privileged the aesthetic as much as science and technology, and what would this mean for innovation and productivity? If the qualifying expenditures for R&D tax reliefs were widened to embrace arts R&D, while the arts learned to structure inquiry towards compelling data production, what new interdisciplinary business solutions to society’s problems might we see?

Sources

1 David Maggs, Art and the World After This. Metcalf Foundation, June, 2021.

https://metcalffoundation.com/publication/art-and-the-world-after-this/

2 Bill McKibben. “What the warming world needs now is art, sweet art,” Grist Magazine. April 2005. http://grist.org/article/mckibben-imagine/

3 David Maggs and John Robinson. Sustainability in an Imaginary World: Art and the Question of Agency. Routledge, New York, 2020. See, in particular, chapters 7 & 8.

4 Hasan Bakhshi, Alan Freeman and Radhika Desai. “Not Rocket Science: A Roadmap for Arts and Cultural R&D,” MPRA Paper 52710, University Library of Munich, Germany, revised 01 Jan 2010.

https://ideas.repec.org/p/pra/mprapa/52710.html

5 Hasan Bakhshi and Elizabeth Lomas. “Defining R&D for the Creative Industries,” Nesta/AHRC/UCL, 2017. https://ahrc.ukri.org/documents/project-reports-and-reviews/policy-briefing-digital-r-d/

6 Hasan Bakhshi, Jonathan Breckon and Ruth Puttick.”Understanding R&D in the arts, humanities and social sciences,” Journal of the British Academy, volume 9.

Hasan Bakhshi

Hasan is Director of the AHRC-funded Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre, a Nesta-led, AHRC-funded research consortium of ten universities, charged with improving the evidence base for policies to support the UK’s creative industries. Prior to Nesta, Hasan worked as Executive Director at Lehman Brothers, as Deputy Chief Economist at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and as an economist at the Bank of England. He has published widely in academic journals and policy publications on topics ranging from technological progress and economic growth to the economics of the creative and cultural sector. He is also Adjunct Professor of Creative Industries at the Queensland University of Technology, has an honorary Doctorate from the University of Brighton for his work on economic policy for the creative industries, and in the 2015 New Year’s Honours was awarded an MBE for services to the creative industries. Hasan is a member of the government’s Creative Industries Council, the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport’s Science Advisory Council and Advisory Board for its Culture and Heritage Capital Framework. In 2017, he was elected to sit on the Royal Economic Society Council.

Picture © NESTA

David Maggs

David Maggs carries on an active career as an interdisciplinary artist and researcher focused on arts, climate change, and sustainability. He is the founder and pianist for Dark by Five, has written works for the stage, and collaborated on large augmented reality and virtual reality projects (see Mummer’s Journey). David is the artistic director of the rural Canadian interarts organization Gros Morne Summer Music, and founder and co-director of the Graham Academy, a youth training academy founded in honour of his teacher and mentor, Dr. Gary Graham. He initiated and coproduced the CBC doc channel film The Country, exploring the Canadian government’s handling of indigenous identity in Newfoundland. As a fellow at the University of Toronto’s Munk School for Global Affairs, David co-authored Sustainability in an Imaginary World (Routledge Press, 2020) with mentor and longtime collaborator John Robinson. He is former senior fellow at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Sustainability in Potsdam, Germany, where he led work on culture and climate change. Currently he is the inaugural Innovation Fellow in residence at the Metcalf Foundation where he will explore the role of art in society, with particular focus on innovation, climate change, and cultural policy.

Picture © Grady Mitchell

A Tribe Called Zimbabwe

Program Lead at Magamba Network

A Tribe Called Zimbabwe