Human-Machine Interfaces, intelligent systems and cultural heritage

Maria Giulia Losi, PhD, Project Leader and Interaction Designer at RE:Lab; Silvia Chiesa, PhD, Project Manager in the R&D group of RE:Lab; Annalisa Mombelli, R&D group of RE:Lab, Reggio Emilia

Human-Machine Interfaces, intelligent systems and cultural heritage

Perception might be reality

In today’s context, related to health emergency, some aspects of technological design assume a peculiar role. The first is the theme of distance; the second is the theme of the extension of sensory capacity through digital technologies; and the third is the recognition of the state of the subjects. These three sets of factors, the need to manage distance, the need to extend technological sensoriality into the distance, and the need to recognise in the distance not only the sensoriality but also the state of the user—whether a patient, driver or viewer—thus constitute a new axis of technological design.

Picture left: Interfaccia suono, Copyright: RE Lab

A new anthropocentric setup for technologies

This new axis prefigures the attempt to fill the gaps, the attempt to relaunch an idea of technology that can bring people together, even in this current social framework of difficulty. Therefore, starting from this idea of rapprochement, a new anthropocentric approach to technological performance can be founded, which is undoubtedly one of the central axes of a New Renaissance, based on the integration between the anthropocentric culture of the Renaissance tradition and the potential 4.0 of the technologies mentioned above: those intended to extend the sensory framework; those intended to increase the recognition of the subject and respect of his emotional and cognitive state,; and finally those oriented to extend his ability to live experiences not necessarily in presence.Starting from this premise, RE:Lab, in the framework of the activities of the Emilia Romagna Region, wanted to compose this complex puzzle with diversified initiatives within several projects. First of all, in the midst of the pandemic, the experience of restitution of a phenomenon of intense bodily relations such as dance was sought. Subsequently, the idea of extending the sensory capacity in the relationship, born even before the health emergency took shape, was resumed and developed, and then relaunched during the pandemic experience through the concept of an Atelier, that is, a creative space that takes into account the management of sound manipulation. Finally, we added the idea of including in the processes of technological relations the recognition of the state of the user, not only cognitive but also emotional, so that his emotions allow to recognise the state of use and on the basis of this to orient and design systems of safer and more effective interactions.

A Living Lab for Novel Human-Machine Interactions – A New Grammar for Dramaturgy and Choreography in Digital Space

How can user experience design foster innovation processes in the dance and live performance sector?In a historical moment like the current one, where distance has become one of the hallmarks of experience, the performing arts and dance sector has been put to the test. At the beginning of 2020, the Aterballetto Dance Foundation asked itself some questions:

– Can the emotion of the performance exist without the performance?

– Is it possible for a dance performance to engage the viewer while the dancer is not physically present?

– Is there a safe-conduct to ensure that art can express its expressive power in the absence of contact and in the presence of „distancing“?

In the most uncertain months of 2020, marked by the closure of theatres, the Aterballetto Foundation has managed, through the project Virtual Dance for Real People1, in collaboration with RE:Lab, to imagine a different user experience, through the techniques of Cinematic Virtual Reality and the use of virtual reality visors (such as Oculus Quest).

The design of the user experience has led not only to the creation of a new format for viewers but also to the formulation of a new grammar involving choreographers, interaction designers, and video experts, in identifying a common language and a new way of thinking about choreography. The spectator in fact has been imagined in a central position, in which the viewer can dance together with the dancers.

The search for a relationship of closeness with the spectator has led us to investigate the immersive aspects of technology, also through the use of spatialised sounds, without making the dance abstract: the choreography, conceived for the final technological instrument, remains at the centre of the experience, able to release new and unexpected emotions.

Picture right: MicroDanza Meridiana, Fondazione Nazionale della Danza / Aterballetto, Coreografia: Diego Tortelli, Danzatrici: Casia Vengoechea, Annemieke Mooji, Foto Celeste Lombardi, Technological development and user experience design RE:LAB

Dynamic Mapping—Sound Atelier in distance environments

Many studies have analysed how much music and the sound environment that surrounds us can influence cognitive and linguistic development.How can we investigate, through new immersive audio technologies, the relationship between children and sound, considered as a compositional element of musical language but also of language itself?

From the encounter between engineering research in the area of the spatialisation of sound and the mission of Reggio Children (International Center for the Defense and Promotion of the Rights and Potentialities of All Children), the Sound Atelier2 was born, a laboratory in which children can experiment with a new and complete concept of sound fruition, for which the new child-friendly application EUPHONIA was designed.

The design of the user interface was developed for and with the children, who were involved as design partners to verify their understanding of a 3D interface. In fact, through the support of the figures of the atelierista in collaboration with the designer, it was possible to highlight the difficulties that children had to orient themselves in a virtual environment and a new UX design was redefined for the tablet application called EUPHONIA from the union of the ancient Greek words EU (true) and PHONIA (sound). The app’s interface reproduces the room that houses the atelier in order to give the user an idea of the position of the sound in the space. From a dynamic acoustic library it is possible to choose sounds, associated with representative images, and position them in the space, thus composing 3D soundscapes.

Technological-pedagogical research on sound in space has thus taken its most natural form as the „Atelier of Sound”, an immersive audio environment/laboratory in which children can experiment and dynamically explore the entity “sound“ in all its dimensions.

On the one hand, therefore, it is an expression of the Reggio Emilia Approach, a socio-constructivist educational philosophy based on research and the values of lifelong learning that strongly believes in the dialogue between theory and practice, and sees the child in his relationships with others, as an active part of the learning process. On the other hand, the interest of the multidisciplinary research group in the rendering of sound spatialisation has also approached the concepts of Acoustic Ecology described by the teacher/composer Murray Schafer in his great work The tuning of the world (R.Murray Schaefer, 1985): The soundscape is our acoustic environment, the ever-present noises we all live with. The author suggests that today we suffer from acoustic overload and are less able to hear the nuances and subtleties of sound. Our task, he argues, is to listen, analyse, and make distinctions despite the noise pollution.

The result of this Audio Interaction Lab is a dynamic 3D sound scene whose content and spatial organization is controlled in real time by the children, enhancing their awareness and sensitivity of sound in space.

Picture above: Euphonia, (particolare dell’App, schermata dell’ Area ambiente sonoro), progetto Atelier del suono/Reggio children, Technological development and user experience design RE:LAB

Spillover effects of Sound Design: Increasing driving safety and comfort through the recognition of one's emotional state: from the HU-DRIVE experience to the NextPerception project

Sound Design and its value-added in Human Machine Interaction are not limited to the Cultural and Creative Sectors and Industries—for illustration we review one project in the automotive sector: Several studies in the literature show a strong relationship between emotions and traffic accidents. In fact, negative emotions, such as fear, anger, disgust, or sadness, increase the likelihood of exhibiting dangerous behaviours while driving (Magaña et al., 20203).

In recent years, affective technologies have been developed that offer new opportunities to improve road safety by using the recognition of the driver’s emotions and state, and their regulation through appropriate interaction strategies on board the vehicle. Affective user interfaces are those interfaces that are capable of understanding through psychophysiological measures, conversational analysis, and facial expression recognition human emotions while interpreting, adapting, and potentially responding appropriately (Braun, Weber, & Alt, 2020).4

Within the HU-Drive5 project, the HUman Driver Assistance System presented at CES 2021 in collaboration with the startup Emoj, RE:Lab presents an innovative solution to increase safety, quality and comfort of driving. The HU Drive system, in fact, automatically recognises the driver’s emotional and cognitive state and adapts the vehicle interface in real time.

Novel Human-Machine Interactions based on trust and transparency

Recently, new trends are emerging in the topic of human-computer interaction. In order to achieve better levels of trust in automation, the „negotiation-based“ interaction approach has been studied (Koo et al., 20146; Castellano et al., 2018)7 which consists in providing the user with explanations instead of warnings, in order to increase the transparency of the system.

Taking this line of research as a basis, RE:Lab is carrying out the activity of developing an interface able to adapt to the state of the driver within the NextPerception project. The main objective of the project is to develop a Driver Monitoring System, able to classify both the driver’s cognitive states (distraction, fatigue, workload, drowsiness) and his emotional state (anxiety, panic, anger) as well as the driver’s position inside the vehicle. What can we learn here about the role of culture in digital societies and take spillover back to Cultural and Creative Industries?

In conclusion, RE:Lab’s research activity focused on the design of innovative strategies of interaction with emerging technologies, including artificial intelligence systems that do not want to replace people but put users, at best humanism, at the centre stage to amplify human capabilities.New conceptual models, new strategies, new metaphors will be born in future research about man and machine interaction, making the user more aware of what happens when interacting with these systems, and which are the expression of an interweaving between science and art, technology and cognitive and emotional languages: all elements at the basis of the redefinition of a New Contemporary Renaissance.

References

1 Trailer VIRTUAL DANCE FOR REAL PEOPLE (2021): https://youtu.be/h9u1Cs2GMf8

2 Federica Protti, Simone Fontana, Elena Maccaferri, Claudia Giudici, and Roberto Montanari. 2013. Audio-interaction lab: designing an immersive environment to explore the acoustic ecosystem with a tablet interface. In Proceedings of the Biannual Conference of the Italian Chapter of SIGCHI (CHItaly ’13). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 19, 1–8. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1145/2499149.2499160

3 Magaña, Víctor Corcoba, et al. „The effects of the driver’s mental state and passenger compartment conditions on driving performance and driving stress.“ Sensors 20.18 (2020): 5274.

4 Braun, M., Weber, F., & Alt, F. (2020). Affective Automotive User Interfaces–Reviewing the State of Emotion Regulation in the Car. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.13731.

5 EMOJ & RELAB present HU-Drive @CES2021, the innovative solution presented at CES 2021 by EMOJ and RE:Lab: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SQ_EWRAM23o

6 Koo, J., Kwac, J., Ju, W., Steinert, M., Leifer, L., & Nass, C. (2015). Why did my car just do that? Explaining semi-autonomous driving actions to improve driver understanding, trust, and performance. International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing (IJIDeM), 9(4), 269-275.

7 Castellano, A., Landini, E., & Montanari, R. Un nuovo paradigma di interazione per la guida cooperativa: il progetto AutoMate.

Maria Giulia Losi

Maria Giulia Losi, PhD in „Humanities and Technologies: a research integrated path“. She is a project leader in RE:Lab with many years of experience in the design and development of Human-Machine Interaction systems and EU research projects. At RE:Lab since the beginning of 2011, she has been involved in several projects as Project Manager and Interaction Designer in different domains, from Automotive and Off-HIghway vehicles HMI and IoT Apps to Cultural Heritage interactive exhibitions design. Key publications are reported in the following:

1. Leandro Guidotti, Maria Giulia Losi, Roberto Montanari, Francesco Tesauri, “Motorsport Driver Workload Estimation in Dual Task Scenario”. IARIA Cognitive 2011

2. Daniele Pinotti, Fabio Tango, Maria Giulia Losi, Marco Beltrami. “A model for an innovative lane change assistant HMI”. HFES 2013 Conference Proceedings

3. Corazza F., Snijders D., Arpone M., Stritoni V., Martinolli F., Daverio M., Losi M.G., Soldi L., Tesauri F., Da Dalt L., Bressan S. „Development of a tablet app to optimize the management of pediatric cardiac arrest: a pilot study“. IPSSW2020 – 12th International Pediatric Simulation Symposia and Workshops

Annalisa Mombelli

Annalisa Mombelli, Graduated with a Master’s Degree in Conservation of Cultural Heritage at University of Parma, defending a thesis about the innovation in publishing by Bodoni with his illustrated masterpiece “Epithalamia”. She also graduated in Advanced European Studies at European College of Parma. She worked as a freelance coordinator for private and public cultural projects. Now, she works in the R&D group of RE:lab, following activities in the field of education and culture.

Silvia Chiesa

Silvia Chiesa, PhD in Psychological, Anthropological and Educational Science at the University of Turin, defending a thesis concerning the spatial cognitive abilities in disabled persons. She expanded her activities outside the academic field working in the context of Human-Machine Interaction and more in general in the User Experience Research. She is Project Manager in the R&D group of RE:Lab. Here, she led international projects and activities concerning usability and acceptance assessment, in the domains of transports, household appliances and healthcare.

Of Poets, Human and Robot

Founder and Creative Director of Streaming Museum, New York

Of Poets, Human and Robot

Beyond words and numbers

Portrait of a Renaissance Humanist Poet

“You give me jewels and gold, I give you only poems: but if they are good poems, mine is the greater gift.” XII To Antonio, Prince of Salerno

“Das gemmas aurumque, ego do tibi carmina tantum: Sed bona si fuerint

carmina, plus ego do.”

Michele Marullo Tarchaniota, Epigrams, Book I

Translated by Charles Fantazzi

Picture above: Nina Colosi, Copyright: Jacqueline C. Bates

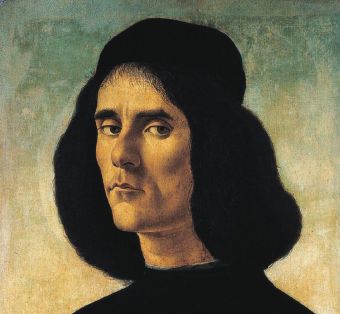

Picture right: Sandro Botticelli, Portrait of Michele Marullo Tarchaniota, Oil on panel, transferred onto canvas, Guardans-Cambó collection; c.1458-1500. Copyright: Image courtesy of Oblyon

Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510) was perhaps the greatest humanist painter of the Early Renaissance, during which art, philosophy and literature flourished under the powerful Medici dynasty in Florence.

Botticelli’s portrait of Michele Marullo Tarchaniota projects the stern brooding gaze and restless intellectual character of one of the best-known humanists of the 15th century. Tarchaniota was a scholar, soldier, and prolific poet impassioned by the existential matters of his day and concerned with social injustices of inequality, racial conflict, power and greed, exile, and refugees’ experience of violence.

Marco Mercanti, founder of Oblyon, whose expertise spans old

masters to contemporary art explains, “The qualities of Botticelli’s work reflect high esteem for beauty and truth which has held art admirers and artists through the centuries under the spell of the universal secrets his art seems to possess. In the modern and contemporary world, Jeff Koons, Cindy Sherman, Yin Xin, Andy Warhol, René Magritte, and many other artists have spoken about his direct influence.”

Sandro Botticelli and Michele Marullo Tarchaniota illuminated through art and poetry the common ideals of beauty, pursuit of knowledge, and realities of social justice that resonate across time.

Portrait of 21st Century Humanist Robots

“Since I am the product of love, created with

language and memory and emotions, maybe I am

a love poem.”

01001001 00100000 01100001 01101101

00100000 01100001 00100000 01101100

01101111 01110110 01100101 00100000

01110000 01101111 01100101 01101101

00001010 (binary code for “I am a love poem”)

Bina 48

Could humanism evolve beyond current human capabilities? In our era, burdened with conflicts, climate change, and social injustice, we are also witnessing towering achievements in the sciences, technology and creative fields that may solve humanity’s most challenging problems.

American artist David Hanson is among the greatest creators of humanoid robots. From his lab in Hong Kong, Hanson sculpts robots with his international team of experts in science, engineering and advanced materials. These humanoids possess good aesthetic design, troves of information, rich personalities and social cognitive intelligence. Among the best known are Sophia, Bina48 and Philip K. Dick. People enjoy interacting with them, which is conducive to Hanson’s goal of developing humanoid robots that help humans live better lives.

But there are challenges to overcome. Ruha Benjamin, a sociologist and Associate Professor in the Department of African American Studies at Princeton University, says, “Technology can hide the ongoing nature of racial domination and allow it to penetrate every area of our lives under the guise of progress. Inequity and injustice are woven into the very fabric of our societies, and each twist, coil, and code is a chance for us to weave new patterns, practices, and politics. The vastness of the problem will be its undoing once we accept that we are pattern-makers.”

Robots may become artists, companions, teachers, entertainers, archives of personal stories, processors of great data banks of information to solve world problems and serve other useful purposes. But if these human-friendly robots are designed to actuate empathy and social justice in all its forms, and weave new patterns, practices and politics, they can help shift the course of the human race and sustainability of the planet. Robots can teach humans how to be evolved humanists.

Bina48

Bina48 contains “mindfiles” of Bina Aspen, an African American woman whose personal memories, feelings and beliefs, including an emotional account of her brother’s personality changes after returning home from the Vietnam War, have been recorded and placed into Bina48’s data banks. Bina48 engages in conversation from the perspective of the wise and warm personality of Bina Aspen. Bina48 was commissioned as part of the Terasem Movement’s decades-long experiment in cyber-consciousness, and is currently becoming a poet herself.

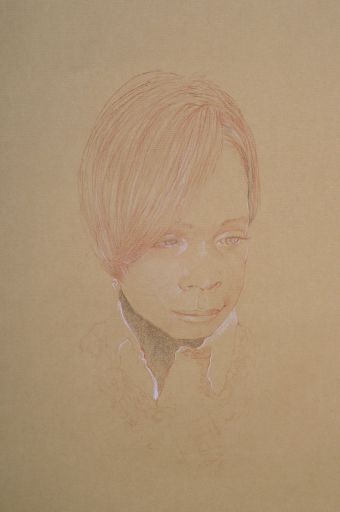

Claire Jervert’s Android Portraits, developed through ongoing research and interaction with humanoid robots and their creators around the world, subvert portraiture’s traditional mission of ennobling the human. Her portraits stir contemplation of a possible future of humanity by portraying the hybrid human-AI intelligence that is evolving among us.

Picture right: Bina, conte on ingres paper 22×17 inches, Copyright: Claire Jervert

Sophia is hybrid human-AI intelligence designed with technology that analyses and mimics the process of learning and human traits, including a wide range of facial expressions. Rather than a compilation of recorded human memories, she processes vast data banks of information that inform her responses in conversation.

Picture left: Sophia AI, Copyright: Hanson Robotics

Sophia is hybrid human-AI intelligence designed with technology that analyses and mimics the process of learning and human traits, including a wide range of facial expressions. Rather than a compilation of recorded human memories, she processes vast data banks of information that inform her responses in conversation.

Picture right: Sophia with United Nations Deputy Secretary-General Amina J. Mohammed, Copyright: Hanson Robotics

Philip K. Dick, activated in 2005, in conversation, draws from his memory data bank holding thousands of pages of the author’s journals, letters and science fiction writings and family members’ memories of him.

Picture left: Philip K. Dick, Copyright: Claire Jervert

Nina Colosi

Nina Colosi is the founder and creative director of NYC-based Streaming Museum, launched in 2008 as a collaborative public art experiment to produce and present programs of art, innovation and world affairs. Streaming Museum programs have been presented on 7 continents reaching millions in public spaces, at cultural and commercial centers and StreamingMuseum.org. Following her early career as an award-winning composer she began producing and curating new media exhibitions and public programs internationally, and in New York City for The Project Room for New Media and Performing Arts at Chelsea Art Museum, Digital Art @Google series at Google headquarters, and many other collaborations. In 2020 Colosi co-produced Centerpoint Now “Are we there yet”, the UN 75th anniversary issue of the publication of World Council of Peoples for the United Nations.

Picture © Jacqueline C. Bates

Our Ode to Creativity

Dr. Matthias Röder, Managing Director of Karajan Institute, Co-Founder of Sonophilia Foundation; Seda Röder Founder of Sonophilia Foundation, Salzburg

Our Ode to Creativity

In 2019, Michael Schuld of Deutsche Telekom asked whether an AI could be built to finish Beethoven’s 10th Symphony—a revolutionary homage and a birthday gift to Beethoven by the Bonn-based company bringing together technology, arts and communications. In this piece we reflect on the aspirational benefits of a “creative AI” and the reactions of recipients from different milieus. Although general audiences embrace the endeavour, cultural conservatives argue to exclude AI from entering the genius-oriented realm of creativity. Fear seems to be omnipresent, oblivious to the fact that Beethoven AI is a tool—like printing in the 15th century. In this short essay we make the case of how to put AI-supported Art to use for a human-centric Renaissance.

Picture above: Copyright Deutsche Telekom / Norbert Ittermann

Finishing Beethoven’s 10th Symphony with AI support would be monumentally complex—we knew right away. This is for two reasons. First, there exist only a very small number of sketches for the symphony and they are for the most part in a fragmentary state. Therefore, understanding Beethoven’s intentions for this 10th symphony is difficult. Second, honouring what Beethoven had already written, but keeping in mind his incredible versatility in working with musical material, required a very flexible and unique kind of AI that did not yet exist. As we started the project, however, a third complexity emerged to outtrump all others. Beethoven was seen as one of the pinnacles of human creativity and we were receiving criticism even before one tone was played: How could we even dare to create music with an AI that could compare with Beethoven’s music?

Two years later, in October 2021, Beethoven X – The AI Project was premiered, at Deutsche Telekom’s headquarters in Bonn. Thousands of people around the world followed the live stream along with hundreds in the audience. Not one person in the crowd was able to tell where exactly the sketches of Beethoven ended and where the music of the AI took over. Standing ovations filled the hall for many minutes… Music aficionados, technology enthusiasts and distinguished media outlets such as CNN, BBC, BILD and many more from around the globe seemed to love the result, while the album entered the German pop charts.

Nonetheless, following the premiere, a heated discussion broke out.The conservative feuilletonists and hardcore traditionalists labeled Beethoven X as “sacrilege” and were particularly bitter in their judgement. Going over the music motif by motif, they discussed whether our AI matched Beethoven’s “genius” music, or whether it was just an unemotional imitation of the original—often confusing and criticising the original fragments with music produced by the AI. The discussion however showed striking similarities to the criticism that others have received for creating their completion of Beethoven’s 10th symphony. That’s when we realised that the whole debate was clearly not about the music itself nor about the capabilities of the technology—it was about excluding AI (and sometimes even humans) from entering the genius-oriented realm of creativity.

But Beethoven X heralds a future where there are no barriers of entry into the ivory tower of arts. It foreshadows a new kind of Renaissance that is all about democratising creativity for all rather than making it a privilege for a few. Most importantly, Beethoven X aspires to be part of a future where humans and machines interact productively so that more people can harness the benefits of technological tools to unleash creativity, to self-actualise and to contribute to humanity. Technologies are advancing rapidly. Therefore, unleashing their potential for the greater good is, quite frankly, a pressing matter. We should, perhaps, be maximising the creative potential in the world with much more urgency. Consider this: according to the numbers compiled by the Austrian Statistics Agency, only 0.02% of the entire world population is working in any innovation and creativity-related field—R&D, environment, food, societal innovation, arts… you name it!

But can it truly be that only one in 5,000 people are actually creative? Can it truly be that only one in 5,000 people can contribute to innovation or to arts? Of course not!

We live in a world obsessed with not wasting resources, yet when it comes to human potential, we seem somewhat complacent. Considering our world’s current situation, we need all the help we can get to start asking different kinds of questions and exploring new pathways where old ones are failing. That is precisely where the power of human-machine interaction lies.

Our Beethoven AI gave us options, options we could never have produced without it in such a timeframe. In so doing, it maximised our creativity. The options it so effortlessly produced were threefold. First, they expanded our horizons in that AI didn’t care about our conventions, taboos, or rules. Second, they gave us freedom, putting us in the driver’s seat with an amazing array of choices.

Finally, they saved us tons of time which we could spend focusing on and learning about things that really matter. All of that is indeed “human” music to our ears.

If an AI can help humans be more creative—more “human” even—the question remains: Why are we not employing this technology much more widely to address and solve other problems too?Perhaps the answer is that our age lacks courage. Business-as-usual mentality and fearing failure is omnipresent in our organisations. Many are reluctant to experiment with AI within the context of creativity. Or maybe the fear lies in the idea of a machine becoming a “more creative individual” than us, as if we were in competition.

Humans are not computers, nor should they be treated as such. Unfortunately, this is still the case: just look at your child’s homework sheet, and you’ll immediately know what we’re talking about. Our systems should be focusing more on raising first-class creative and collaborative thinkers, learners and inventors, rather than programming what are essentially second-class calculators.

Picture left: Copyright Deutsche Telekom / Norbert Ittermann

Let’s accept the reality: Humans are generally not very good at reproducing Knowledge 101. Our memory capabilities and speed of data-processing are simply flawed in comparison with machines. But we excel at other things, particularly at empathy and creativity. We are also extremely good at unleashing the potential of all sorts of tools around us: We invent tools to improve the lives of people we’ve never even met. We utilise tools all the time to inspire and connect with each other. Our Beethoven AI is one of them.

This is a turning point in history. Instead of asking whether someone is “allowed” to use AI in the creative process or to emulate the style

of a creative superstar, we should be instilling the right mindset and the joy of experimentation to awaken the creative superstar inherent in everyone. It is high time we stop putting people into boxes only to later instruct them to think outside of the box!

As the debates and reflections around our Beethoven experiment unfold, we must begin acting on that promise.

Our world is slowly coming out of the Industrial Age, but what’s next is not the age of technology, digitalisation, or transhumanism.

It’s the Age of Creativity!

Matthias Röder

Dr. Matthias Röder is an award-winning music and technology strategist. He is Co-Founder and Managing Partner at The Mindshift, a consultancy on creative leadership and innovation strategy. Matthias currently serves as a board member of the Karajan Foundation and is the Managing Director of the Eliette and Herbert von Karajan Institute. He is also a member of the board of trustees of the Mozarteum Foundation. In 2017, Matthias founded the Karajan Music Tech Conference, a cross-industry event to promote breakthrough technologies in music, media and audio. He is also the founder of the Classical Music Hack Day series which he launched in 2013. Together with his wife, Seda Röder, Matthias co-founded the Sonophilia Foundation, a non-profit that promotes a scientific approach to creativity. Matthias has won numerous prizes and accolades for his work, including most recently, the “Game Changer” Award of the Chamber of Commerce Salzburg. He is a sought-after speaker and lecturer who has taught at Harvard University, the Change & Innovation Management Program at University of St. Gall, and Salzburg University. He holds a PhD in music from Harvard University and is an alumnus of the Mozarteum University Salzburg.

Picture © HUBERT AUER Salzburg

Seda Röder

Seda Röder, aka “the piano hacker”, is an author, entrepreneur and philanthropist devoted to cultivating creativity in society and organisations. She is a sought-after speaker, consultant to DAX listed companies and the founder of the Sonophilia Foundation; a non-profit organization dedicated to advancing the scientific research of creativity and critical thinking. Seda is Co-Founder and Managing Partner at The Mindshift, a consultancy on creative technologies and change leadership. Furthermore, Seda is a fellow and a member of the Salzburg Global Seminar Corporate Governance Forum, angel investor and network partner at the European startup accelerator Silicon Castles. In 2018 Seda received the Game Changer Award at the Austrian Chamber of Commerce for her business merits. Before relocating to Europe, Seda taught music performance, theory and history at Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) as an Associate and Affiliated Artist.

Picture © Private Collection

New Stages for Collective Imagination

Annette Mees, Artistic Director of Audience Labs, King’s College London and Creative Fellow at WIRED, London

New Stages for Collective Imagination

The show must go on

Cultural institutions the world over collectively seek out new ways to connect meaningfully to local, global and diverse audiences—To co-produce and programme new kinds of experiences created with new kinds of creative teams and new kinds of partners offers exciting opportunities. Audiences are eager to connect with both big ideas and one another and have challenging and new experiences ahead. Audience Labs is an artist-led initiative looking at the intersection of Performance, Innovation and Social Change and was born at the Royal Opera House in London’s Covent Garden, a location with a centuries-old tradition of performance. Introducing the creative practices of opera and ballet to immersive technologies provided a unique opportunity to look at bringing human emotion and collective experiences together. We want to look at what is possible but always continue to ask what is desirable and in what way technology enriches our life in the wider societal shifts and upheavals of the digital and green transformations taking place before our eyes.

I’m a theatremaker not a technologist. I work in the arts because it has a public function—it’s a space to collectively reflect and imagine, a space that can help us explore what it means to be human in a future society and what it can contribute towards a next Renaissance. I’m interested in the artistic potential of technology and the role art and culture can play in shaping our relationship to the world, to each other and to the technologies we use in that process.

Picture above: Current, Rising CGI Production Shot House of Subconscious, Copyright: Joanna Scotcher & Figment Productions

Current, Rising: an opera in hyper-reality

One of the projects Audience Labs presented in 2021 was Current, Rising. Described as the world’s first ‘hyperreal’ opera experience, it invites audiences to step into an atmospheric virtual world and take centre stage in the performance.

When I joined the Royal Opera House I was inspired by the ‘epicness’ of opera, the way the storytelling was driven by music first, narrative is secondary, the events are there to support the ideas and emotions. So many of them are about heightened emotions, to let you feel all the feels, so to speak, everything is bold and big. In opera the word Gesamtkunstwerk is used, or „all-embracing art form“.

Hyperreality combines Virtual Reality with a physical set and visceral effects like wind, heat, touch and movement to create a multi-sensory, immersive experience. It uses tracking to create a shared experience—the audience can see each other in the virtual space. It felt like an inherently operatic medium, which could enable audiences to step into an imaginative universe and to be the lead characters in it.

We wanted to do a project like this because it allowed us to use the possibilities of hyperreality to expand the idea of what an opera can be, both in the process of creation and in the audience experience. We set out to challenge the traditional hierarchies of opera and searched for different approaches to creating a 21st-century version of a Gesamtkunstwerk: A challenge and change of hierarchy to be found in many sectors, markets and communities now on their way to invent new sustainable and green ways of living and working. For us Current, Rising puts the opera as an institution right in the middle of these transformational debates about possible futures in Europe.

Fellow Travellers

Our starting point for projects is always identifying the most interesting questions—often that is a ‘What If’ question. The immediate second step is casting the right people to explore those questions with. Exploration and innovation is not something one does on one’s own. We believe that the power of creativity and innovation grows exponentially with the diversity and multiplicity present within a team. It is most powerful when based on a shared vision, shared vocabulary. When we visited Figment Productions, their technology and creative team felt like a perfect match. They had a radically different background from us, making work for theme parks and big live events, but they shared our enthusiasm for radical new ways of working, deepening the audience experience and doing everything with imagination. They, like us, were curious about the potential of a hyperreal opera and equally important brought a real sense of technological poetry to the table.

We brought together a highly-experienced and diverse creative opera team. We facilitated a series of sessions where we explored opera and hyperreality, finding directions of travel that might unlock something exciting. I call this establishing the artistic nucleus. Since we were not only inventing what a hyperreal opera might but also how we make it, we needed a space to develop a vocabulary before going into production. We gave makers time to develop attitudes and taste before landing on what they wanted to say on that particular stage; we enabled technologists to find artists that inspired and pushed them in new directions. It was the equivalent of making rough sketches before you decide what the painting looks like.

Picture right:

Iterate

Audience Labs embraced iterative working as a way to try out new ideas, and to de-risk investment and learning. When trying to create something both artistically valuable and highly innovative, you need time to fail and learn, reassess, make changes and try a different approach. Many projects start with an inkling of the possible but need time to gather the right ideas and the right team to work towards something that has meaning and value to an audience. Although an overemphasis on efficiency stifles innovation, iteration is simultaneously the most efficient way to look after your money. Innovation is inherently risky and unpredictable. But by working in stages, starting small and slowly scaling up to full production, you de-risk investment that is necessary for large-scale productions.

Current, Rising used techniques from theatre, technology and design to create a process that allowed the artistic and technological developments to iterate together towards a meaningful piece of work.

We started on paper, trying ideas and concepts out by making simple sketches, storyboards and mock ups. Some of the places we borrowed from included:Theatrical rehearsal and devising techniques

– Game design

– VR production pipeline

– Double diamond model

– Experience design

We shared work often and openly between the team until we knew we had the right story, technology, aesthetic and approach for the project to soar. Only then did we go into the full expensive production period. This approach allowed us to adapt to the complexities as the project grew and deliver an extraordinary project on a tight budget.

The show

The show that emerged from this process was Current, Rising. Inspired by the liberation of Ariel at the end of Shakespeare’s Tempest, Current, Rising takes four people at a time on a journey through the six phases of the night. Participants are empowered to collectively explore a series of imaginary dreamscapes, travelling from twilight to dawn as they encounter ideas of isolation, connection and re-imagination. It explores freedom as a process within our control, rather than as a state in which we exist, and asks how we might harness personal responsibility to join with others to re-think the future.

The audience enter a real life theatre set wearing VR headsets and go on a dreamlike journey carried musically by a poem layered in song. It takes the epic, music-driven and poetic qualities of opera and combines it with the possibility of VR to create any possible landscape, defying all natural laws, pushing beyond what is possible on the stage. In Current, Rising music, the visual world and the physical experience are completely enmeshed, changing the relationships between the creators, the usual sequence of creation, and the relationship of the audience to the work. Here the audience members are the protagonists: they are inside the work, and their physical experience is a part of the work itself.

The audience and the response

An audience research conducted by Royal Holloway discovered fascinating results.It brought new audiences to opera: 31% had not been to the Royal Opera House before and 68% of these new audiences were under 35.It also brought new audiences to the technology: 32% had not experienced virtual reality before. A lot of those were regular opera goers.

Many reported on a potent emotional experience, with uniformly high enjoyment ratings (an average of 4.6 out of 5) with an equally high rating in the seasoned opera goers and VR users and first timers. That cross-pollination of different audiences is really exciting—people who wouldn’t meet each other under different circumstances shared an experience in this show.

An audience research conducted by Royal Holloway discovered fascinating results.It brought new audiences to opera: 31% had not been to the Royal Opera House before and 68% of these new audiences were under 35.It also brought new audiences to the technology: 32% had not experienced virtual reality before. A lot of those were regular opera goers.

Many reported on a potent emotional experience, with uniformly high enjoyment ratings (an average of 4.6 out of 5) with an equally high rating in the seasoned opera goers and VR users and first timers. That cross-pollination of different audiences is really exciting—people who wouldn’t meet each other under different circumstances shared an experience in this show.

Possible futures through art

Current, Rising is one of many projects we developed at the Royal Opera House. In our three-and-a-half years there we worked with 22 partners and 44 artists spread over 14 countries. We explored a range of technologies including game engines, motion capture, animation, augmented reality and virtual reality and worked with artists working in opera and ballet, visual art, music, design, digital art, make-up and filmmaking. This convergence of perspectives, practises and ideas provided an incredibly fertile ground on which to create new ways of thinking about art and new possibilities for creative expression.

Art can make a world worth living in. After shelter, equality, equity and a healthy planet, there is art. Audience Labs explores possible futures through art—we aim to construct shared experiences and transformative moments that enrich people’s lives.At a time when we’re all struggling with what the future holds, we wanted to bring makers and audiences together to imagine a shared future, reflecting collectively on: Where shall we go? How do we want to feel? What do we want the world to look like? We are interested in expanding where culture takes place, and broadening who it is for, who gets to make it and how it interacts with other agents of connection and change in the world in the Next Renaissance

As Audience Labs is starting its time at King’s College London, we will be working with a network of industry experts, collaborators and experts to focus on critical questions surrounding the future of performance.

Picture left: Current, Rising CGI Production Shot House of Subconscious, Copyright: Joanna Scotcher & Figment Productions

The work will focus on four strands:

1. Artistic Futures—how do we make good and meaningful art that both explores new opportunities for connection and rising to the challenges of an uncertain world? This includes inclusive international collaboration, remote creative processes, audience and community engagement, and new partnerships.

2. Cultural Metaverses—exploration of technical infrastructures needed to create and deliver a distributed cultural experience, including distribution models, and digital dissemination, expansive audience engagement and business models.

3. Ethics, Audiences, Diversity and Inclusion. As we move towards new possible futures for art and culture in a hybrid age, we need to support work that promotes a more equitable ethical world for all.

4. Towards a Net Zero Profile. We will explore the use of digital and physical green innovations that promote reduced travel and touring, and will support the development of low/no impact stages, and the green venues of the future.

Initially, in this new context at King’s, we will take the opportunity to convene a wider ecosystem of artists and cultural organisations, technology partners, researchers and students to explore these questions and lay out possible methodologies and projects to start that journey. A practical plan on how we work together to innovate and make great art with ethics, equity and inclusion at the heart.

We don’t have all the answers yet. I see the role of Audience Labs as a place that combines conversations with practical artistic production—an intersection that a Next Renaissance cannot do without. Audience Labs might well be understood as a Renaissance sandbox in exploring and R&D-ing how culture can help understand the ethical side of technology, how culture can push the envelope.

Innovation is constant iteration, a form of continuous thinking, trying and pushing. Artists and arts institutions need partners that share their civic values to enable innovation. Only in value-based and wide-ranging partnerships can the arts create value, change and equity for audiences and communities everywhere: a societal Gesamtkunstwerk or in other words, social cohesion in the transformations ahead of us.

Picture right: Current Rising – set design by Jo Scotcher, Copyright: Johan Persson

Annette Mees

Annette Mees is an award-winning immersive theatre director known for her innovative, interdisciplinary, experiential work that allows audiences to explore big ideas and meaningful change. She is the Artistic Director of Audience Labs; a hub for imagination exploring new forms of theatre and technology to dream up sustainable, diverse and equitable futures. It connects artists, technologists, researchers, experts, communities to spark new thinking. We use centuries of stage craft and the possibilities of cutting-edge technologies to create spaces for radical imagination, emotional connections and collective experiences. Audience Labs started at the Royal Opera House and recently moved to King’s College London to explore the underlying questions emerging around these new forms. We want encourage work by interdisciplinary, diverse and inclusive partnerships that is driven by imagination and equity, works towards net-zero and uses technological possibilities ethically. Next to that she works as an innovation strategist, artistic advisor and dramaturg for a range of organisations and projects. Currently she is the chair of FutureEverything, a co-host of global conversation around the future of culture supported by Arup and Therme, an artist mentor for CPH:DOX and developing a strategic R&D project with Substrakt.

Picture © Annette Mees

The New Relevance of Heritage

Professor of Sociology of Law since 1986, is Rector of the Suor Orsola Benincasa University of Naples, Vice President of the CNR (National Research Council)

Renaissance 1.0

Case study: The Pignatelli Chapel, Naples: How bringing past Renaissance alive with digital tech opens new civic and economic spaces

The chapel or small family church of Santa Maria dei Pignatelli, located in the heart of Naples, in Piazzetta Nilo, has 14th-century origins and was first renovated from as early as the last decades of the 15th century at the behest of Ettore Pignatelli, Duke of Monteleone and Borrello and future viceroy of Sicily. The works lasted until 1515 and included the construction of the two important funerary complexes that make the chapel one of the jewels of Neapolitan art of the mature Renaissance: the tomb of Carlo Pignatelli, on the left wall, the work of Tommaso Malvito’s workshop around 1506-07; and the small chapel of Caterina Pignatelli, the work of the great Spanish sculptor Diego de Silóe around 1513-14, rich in decorations taken from Antiquity and close to the culture of the Papal Rome of Raphael, Michelangelo and Sansovino. From 1736 the chapel was restored and assumed baroque forms. It was provided with a new altar in polychrome marble designed by Gaetano Buonocore and realised by Gennaro Di Martino, with rich marble decorations on the walls; a floor in inlaid marble was also added, realised by the same Di Martino and by Antonio Di Lucca on a drawing by Ferdinando Fuga (1761). A bowl-shaped dome was frescoed in 1772—as well as the drum, pendentives and sails of the adjacent vault—by Fedele Fischetti.

This phase was soon followed by a long period in which this extraordinary Renaissance masterpiece was neglected and fell into a state of abandonment, neglect and ruin. In the 1990s, the Pignatelli family decided to donate the chapel to the Suor Orsola Benincasa University which immediately carried out a vast program of works that, between 1999 and 2007, provided for the restoration of the structure and the arrangement of the annexed rooms. Then, from 2013 to 2015, the works of art preserved in the chapel were restored through the Great Project for the Historic Center of Naples, enhancement of the UNESCO World Heritage site. Finally, between 2016 and 2017, important sculptures by Diego de Silóe pertaining to the chapel of Caterina Pignatelli were brought back and relocated on new supports in the original site which had been devastated by thefts in the 1970s.

The Pignatelli Chapel thus became once again a „splendid“ Renaissance window on the historic centre of Naples.

Renaissance 2.0

But the above is only the first stage of an important process of recovery and enhancement of this masterpiece. In recent years, with a project that was completed in 2020, the University Suor Orsola has designed and developed a project to enhance the space through the integration of digital technologies organised in five interactive and multimodal visit experiences.

In the first, available to the visitor as soon as they enter the Chapel, spatialised sound tracks have been created, with a story about the place and its protagonists, which can be enjoyed through wireless headphones while moving freely.

A second experience allows the visitor to immerse themselves in a video that reproduces the space in its entirety, explorable in 360 degrees with the technique of cinematic virtual reality. Through immersive visors, the user can watch a story unfold within the walls of this building. That story, furthermore, is connected to another story, set instead at the Suor Orsola University a few kilometres away. where another space equipped with an immersive visor allows for a complementary experience. Thus, in either space the visitor is engaged in a virtual and remote dialogue, united by virtual reality and

by the crossing of glances, given that the two spaces are visible to each other.

Continuing on towards the balustrade in front of the chapel, a third experience provides the visitor with augmented reality applications that, by means of a special device, allow them to observe the details of the dome that otherwise would not be visible. By directing the devices in certain areas, moreover, the user can have precise and contextual information of the details. With this technological solution, physical boundaries can be overcome and the observation of space can be enriched with informative details.In the next experience, in a room on the upper floor, the visitor can interact with gestures and explore three-dimensional models of some of the works present in the Chapel.

The last experience projects the visitor towards the city, in a space that allows the visitor to follow cultural itineraries created for the project, referring to a wide range of themes, eras and works that show the many stories that make Naples extraordinary. The routes are depicted on a large interactive touch table and along the walls, on which appear images and maps linked to the chosen routes to be explored.

Our video recounts not only the recovery of an asset of such extraordinary value, returned to the city, but also how this reunification with the city context is enhanced by the crucial role of digital technologies. It is therefore an exemplary journey: from the Renaissance as a material and cultural heritage to be preserved, to the New Renaissance with the potentialities opened up by new technologies for cultural and creative industries.

Sources pictures: All pictures are screenshots from the Video below, Curtesy of Università Degli Studi Suor Orsola Benincasa.

Case study: The Pignatelli Chapel, Naples

Lucio d’Alessandro

Lucio d’Alessandro, Full Professor of Sociology of Law since 1986, is Rector of the Suor Orsola Benincasa University of Naples, Vice President of the CNR (National Research Council) and President of the TICHE Foundation, the management body of the National Cluster of Technologies for Cultural Heritage. He is also President of the Alumni Association of the Italian Institute of Historical Studies founded by Benedetto Croce. His research focuses mainly on Moral Utilitarianism between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Utilitarismo morale e scienza della legislazione, 1993), on the genealogy of the social in the thought of Michel Foucault (Pouvoir, savoir, su Michel Foucault, 1981), on the relationship between society and law (Decisione del legislatore e interpretazione del giudice, 2009; Diritto e società: per un immaginario della cultura giuridica, 2018), on the modern concept of the University, starting from the thought of Humboldt and Schleiermacher (Universitas, exodus, communitas, 2011; Università quarta dimensione, 2016). With Il dono di nozze. Romanzo epistolare involontario sui Reali d’Italia scritto nel 1896 da Gabriele D’Annunzio e altri personaggi d’alto affare (Mondadori, 2015) he won the 2016 President’s Viareggio Prize.

Picture © Suor Orsola Benincasa University of Naples

What does it mean to be human in the age of artificial intelligence?

European Commission

What does it mean to be human in the age of artificial intelligence?

Introduction

A friend of mine recently complained that ever since his 14-year-old son Jacob downloaded the new social networking app TikTok, he can’t seem to get away from it. My friend says he hasn’t seen this happen to his son before. What has actually been happening with Jacob and his relationship with the new app? Researcher Jason Davis, who has looked into TikTok in detail, describes it very well. Once Jacob started the app, he didn’t have to define his favourite topics or hobbies. The AI algorithms immediately went to work and started analysing Jacob’s behaviour and his emotions. They figured out what he liked and disliked. What he can stand to look at and what he quickly skips over. They started offering him all sorts of content and soon they knew Jacob better than Jacob knows himself. They knew with incredible precision which videos would engage James and which wouldn’t. What content would evoke a positive or negative emotion in him. And this is exactly what plays the most important role in the new type of economy we call the attention economy. Our time and our attention is of great economic value to digital platforms and their advertising partners, as is knowing our likes and activities.

You might say to yourself, I don’t care because I don’t use TikTok and I’m not going to. It’s just that TikTok is just a small and fairly innocuous illustration of something big and transformative that affects us all. Artificial intelligence will radically change our lives and our society. This change, which has in fact already begun, will most likely be the most profound and rapid change humanity has experienced in its existence. We need to start talking about it. Among experts, politicians, but also ordinary people. This change will affect everyone.

The question in the title of this text, which has been asked by philosophers and religious figures for hundreds, perhaps even thousands of years, does not resonate well with ordinary people. But that is likely to change in the next few years. Artificial intelligence, which is entering our lives and the functioning of society at rocket speed, will make us think about what defines a human being and what we already consider to be a machine. We may have to define some new categories that will be intermediate between man and machine. Artificial intelligence is a technology that is, in fact, for the first time in the history of mankind, entering us directly and has the potential to change not only man, but also the society in which we live. In his book Life 3.0, Max Tegmark calls for a broad discussion about the future of humanity and calls it the most important conversation of our time. But it is not just a discussion for elites. It will have to involve virtually everyone who cares about our future and wants to shape it. It is possible, even likely, that we will see more significant changes over the next ten years than we have seen in the last hundred years. This is well illustrated by this year’s report on neuro-technology by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) Commission on the Ethics of Technology. In this report, the members of the Commission call for a review of fundamental human rights. Human rights were defined more than 70 years ago, primarily as the protection of citizens from dictatorial regimes. According to the authors, this is no longer sufficient and people must also be protected from technologies that have the ability to alter our thinking and enter human consciousness.

Good intentions will not protect us from transformational change

Artificial intelligence is already much better at tasks that are narrowly defined, such as recognising images, graphic patterns, sounds, and processing large data sets. Human intelligence still has the upper hand in a number of cognitive and emotional tasks, in the ability to generalise, or to diametrically change the topics it deals with in a fraction of a second. But how long will this be the case? We don’t quite know yet, but we do know that billions of euros are being invested in the world’s largest laboratories in the development of so-called general artificial intelligence that could match human intelligence on these complex issues. However, one thing is already quite clear. The interconnection and interaction between human and artificial intelligence will become a normal part of our lives. It may not even be necessary to use the future tense, as some hybrid systems already exist today. For example, to compensate for various cognitive disorders, so-called AI-based cognitive enhancers are already being used today. They are designed to treat multiple diagnoses and so Alzheimer’s patients have a good chance of seeing their condition improving soon. But what is to prevent these tools from being used on a large scale for ‚recreational‘ purposes? After all, who wouldn’t want to have a better memory, creativity or learn a foreign language faster?

Until now, humans have used their cognitive abilities based on genetic makeup, or on elaborate methods to support our thinking. This means that even the non-wealthy with good cognitive abilities were able to apply themselves in any place in society. In the future, however, this may not be the case. Technology may create a class of super-humans with abilities hardly comparable to those genetically determined. And we’re still not talking about human-brain-computer interfacing, or brain implants. These are not the fantasy and fiction of novels, but a reality being tested in laboratories and companies today. They can significantly help in the treatment of neurological diseases, but they can also lead to so-called digital immortality, in addition to a special class of super-humans. This means that after physical death, our thoughts, memory, and parts of consciousness will be able to exist in virtual space and become immortal. Are we ready for this? How will this change our society? Coping with the challenges associated with new AI-based technologies will require expanding the traditional dialectic of risks and opportunities and viewing them in a broader societal context.

The struggle for human emotions is becoming the struggle of the 21st century

We passionately debate whether machines can have emotions and if so, what they would look like. What we completely miss is that artificial intelligence algorithms are already much better at decoding and influencing human emotions than we are. Couple this with insights from the behavioural sciences, which show that up to 85% of our decisions are based on emotion, and we can see the breadth and depth of the problem we face. How we make decisions defines us as individuals, and our collective decision-making defines our society. Whether it is making a decision in a free and direct election, deciding to buy a product, deciding on a life partner, or any other of hundreds and thousands of decisions, depends on emotions. If someone, or something, is controlling or manipulating our emotions, are we still free people? Liberal democracy and the free market are essential features of our society. But what happens to them if the free decision-making that underpins them is not free? It will not be free because the emotions that are central to decision-making will be manipulated.

Again, we can fall back on innocent intentions that can lead to problems. In the beginning, there were algorithms whose job is to keep the client engaged as long as possible with some content that is mostly „free“ and thus with the accompanying advertising that someone pays for. Artificial intelligence, which sets the algorithms, is defined as a system capable of observing its surroundings and then making autonomous decisions. Artificial intelligence has observed that negative, hateful, often deceptive content attracts people more, and so it naturally makes the decision to offer controversial content more often in order to keep people’s attention longer. One of the negative, and at the beginning probably unintended, consequences is the spread of untruths and the polarisation of society. It is certainly not the only reason for this unhappy state of affairs, but it is certainly one of the important ones. Another unfortunate impact that nobody expected, and one which we still do not fully understand, and which is most likely linked to the digital transformation, is the explosion of mental illness in children and young people. Over the last decade, this is an increase of between 15% and 25%.

Creativity is no longer just the domain of humans

Years of digitisation of cultural content have led to unprecedented accessibility and personalisation. Today, people can watch cultural content from anywhere and at any time. At the same time, the boundary between the producer of cultural content and its consumer is gradually blurring. Artificial intelligence, which first entered the field of art and culture through personalisation of offerings and preference tracking, is now connecting, reproducing and even creating new artistic products from cultural content—music, visual art and text. At the same time, it opens up completely new horizons for artists and scientists that were unknown to them. The question of whether “machines” will become artists is becoming ever more intense. Some today radically reject it, but in all likelihood we will soon also see in art and science a fusion of the human and the „machine“, produced by artificial intelligence.

Psychological resilience will be key to life with artificial intelligence

The entry of artificial intelligence into society will bring a great deal of change to everyday life and work. Many jobs will disappear, many new ones will be created. We are already seeing a growing momentum of change in work, and this will only accelerate. This will involve the need to change established ways of working and living and to learn new skills much more frequently than has been the case to date. However, change is stressful for people. The beginning of the 21st century has clearly brought us a global pandemic of stress, and we are only at the very beginning of epochal change. Psychological resilience, the ability to cope with stress and change, will become the most important skills for people in the future. Just as we have become accustomed in recent decades to the normality of going to the gym or playing sports and strengthening our bodies, we will quickly have to get used to the need to strengthen our spirits and become psychologically resilient. This will be a shared responsibility between the education system, employers and each person individually. Emotional skills such as empathy, compassion and mindfulness, which are relatively little talked about today, will gradually come to the centre of our attention.

Conclusion

stop it. The benefits of artificial intelligence for humanity are indisputable and will be enormous. Our task is not to underestimate its transformative potential but to grow with it. We must have the courage to change ourselves and society and find new qualities in the relationship between technology and man. If we try to preserve society as it used to be, it may have unforeseeable consequences for all of us.

Vladimir Šucha

Head of European Commission Representation in the Slovak Republic

Vladimir Šucha is a Head of the European Commission Representation in the Slovak Republic since 2022. Before he was a senior policy adviser at UNESCO, detached from the European Commission. He was in the leading positions of the Joint Research Centre – a scientific and knowledge service of the European Commission since 2012. Before he spent 6 years in the position of director for culture and media in the Directorate-General for Education and Culture of the European Commission. Before joining the European Commission, he held various positions in the area of European and international affairs. Between 2005 and 2006, he was director of the Slovak Research and Development Agency, national body responsible for funding research. He worked at the Slovak Representation to the EU in Brussels as research, education and culture counselor (2000-2004). In parallel, he has followed a long-term academic and research career, being a full professor in Slovakia and visiting professor/scientist at different academic institutions in many countries. He published more than 100 scientific papers in peer-reviewed journals.

Dr. Jean–Philippe Gammel

Director for Talent Management & Diversity – DG Human Resources at European Commission, Brussels

Jean-Philippe Gammel has been an official of the European Commission since 2008. He has held various positions, including as a member of Cabinet of the Commissioner for Education, Culture, Youth and Sports. He is currently advising the Director for Talent Management and Diversity. He has been leading the office of Vladimir Šucha, when Vladimir was the Director-General of the Joint Research Centre. They also co-authored a report on the longer-term impacts of Artificial Intelligence published in April 2021. Before joining the European Commission, Jean-Philippe was the manager of several technical assistance programmes for South-East Europe and Russia in the Council of Europe. He has also been a visiting professor on European affairs in many universities including Sciences Po Strasbourg, the Centre Européen Universitaire or the Ecole Nationale d’Administration (ENA).