Curable Blindspot of Culture: How Participatory Arts Ignite Positive Change

Ira and Jewell Williams Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures and African & African American Studies at Harvard University and Director of Cultural Initiative at Harvard

The Curable Blindspot of Culture: How Participatory Arts Ignite Positive Change

How Participatory Arts Ignite Positive Change

Culture is our necessary and renewable resource, the fourth pillar of sustainable development, though we often overlook it. The obstacle, in part, has been the word itself. Culture means two opposite things. One meaning is a heritage of shared beliefs, practices, and places, something to be protected rather than tampered with. This is the sense used by most decision-makers who are trained in the social sciences which privilege patterns over disruptions. The other sense is dynamic and familiar to artists and humanists who disrupt patterns and generate new relationships. One understanding is fixed, making culture either an obstacle to development or a fringe area for decoration and leisure, vulnerable to budget cuts. The other is edgy, experimental, and jealous of personal freedom. This difference in meaning causes a blind spot for both mayors and creatives who see past one another when collaborations are urgently needed to adjust outdated attitudes and behaviours that currently block development toward the SDGs.

Picture above: Copyright: Mannheim Public Library, Copyright Yilmaz Holtz Ersahin and Angelika Senft Rubarth

Today, in a post-pandemic world, we have an extraordinary opportunity to bring these visions together into bifocal projects. Shared beliefs and practices need to be refreshed and updated, as effective leaders know. The vast but under-acknowledged bank of evidence is witness to creativity’s power and potential. This includes a literature review by the WHO of 3,000 studies and an evidence base created by the EU and literally 100s of studies in specific cities. On the other hand, artistic interventions need to take stock of their practical effects, beyond personal satisfaction. Otherwise, we waste the creative resources that make us human. Collaborations will make us better citizens who can re-set our societies after the Covid 19 pandemic exposed habitual exclusions such as life and death inequities. Policies of inclusion in post-pandemic cities can count on participatory arts to foster collective belonging. Arts literacy projects will assimilate immigrants; and immigrant arts will enrich the local offer. (See www.pre-texts.org) The gains will be better security, physical and mental health, economic equity, and care in both senses of loving and taking responsibility for society. In sum, the power of arts as inclusion can energise cities across all dimensions.

The reason is clear. When the general population is engaged in collective and creative activities, they build human and social capital, new personal skills, and admiration for fellow citizens. Collaborations as well as supportive investments will harness the power of participatory arts, which is not the same as entertainment. Entertainment can be enjoyed passively, without engaging the energy of dynamic youth. Youth will build or ravage our cities; they actively participate in civic life or they reject it. And rejection can lead to violence, which simmers during lockdowns and has already exploded in many parts of the world. Our opportunity and obligation is to redirect youthful energy—we cannot extinguish it. Policing and punishment alone have not worked well, nor has single-minded investment in infrastructure. A few examples among many highlight the potential.

1. In 1995 newly elected Mayor Antanas Mockus of Bogota, Colombia faced a city mired in despair, violence and corruption. “Time to bring out the clowns,” counselled his Secretary of Culture. “Good idea,” responded the playful mayor. Twenty pantomime artists replaced twenty corrupt traffic police to shame irresponsible pedestrians and drivers. The shared laughter broke an apparently solid pattern of lawlessness. In the first year, there were 51% fewer traffic deaths. Many participatory arts initiatives followed, along with tax reform, transparency and infrastructural development. But art was the icebreaker. Within two administrations, homicides were reduced by almost 70%; tax revenues increased by 300%. This was “cultural acupuncture,” an approach developed from Jaime Lerner’s “urban acupuncture” for Curitiba, Brazil. Mockus added participatory art-making and accomplished astounding results.

2. Edi Rama became World Mayor of the Year in 2004, mostly for painting the grey city of Tirana in bright colours. It did not solve all entrenched problems, but art did act as a catalyst to rediscover a pride of place and greater respect among citizens. An artist himself, Rama saw colour as more than decoration. It is a structural element to revive the civic spirit. “Beauty was acting like our guardsman… where municipal police, or the state itself, were missing.” This was his winning message in a campaign to become Prime Minister of Albania. Over the last few years, Tirana has made astonishing progress in its urban development, creating an urban forest belt of 2 million trees around the city core where children can plant a tree on their birthday. In 56 months, the city created 56 playgrounds in dilapidated parts of the city that act as gathering places and social connection points for all ages.

3. Broad-based music education has long proved to be a problem-solver, ever since El Sistema was established in Caracas over 50 years ago. By now, almost five million young people in Venezuela have benefitted from classical music training. It won’t make them all professional musicians, but it does teach discipline, focus,

collaboration, and dedication to beauty. Music-making, crucially, keeps vulnerable youth off dangerous streets. Many international projects have imitated this program with notable success.

4. This year Peter Kurz of Mannheim was awarded the World Mayor International Award. Much of his long-term work has involved using the arts to foster intercultural understanding and to regenerate troubled neighbourhoods such as Jungbusch. In Mannheim immigrants make up half of the population and former industries are giving way to new business models focused often on the creative economy. Sceptics about arts interventions sometimes object that they are not inspired, like Mockus, or trained as a painter, like Rama, or an engineer, like Lerner. Yet, Mayor Kurz is not himself an artist. Instead, his talent is to listen and to take small, cost-effective risks on art. One was his support for the School for Oriental Music, a unique initiative that a Turkish musician initiated to gather disaffected youth for rigorous time-consuming and community-building music lessons. This is one of many orchestrated ‘cultural acupuncture’ initiatives through which Mannheim addresses security and education by stimulating creative activities that foster diversity and belonging.

As part of a leader‘s toolbox, participatory arts can play a significant role in addressing the global challenges of SDGs. “Had I understood the power of arts to change behaviour and to drive prosperity, I would have made very different decisions as Minister of Development.” (José Molinas of Paraguay, formerly of The World Bank.) His change of perspective inspires a new “Certificate in Arts and Policy” for city governments in order to engage arts toward achieving a city’s goals, and to articulate particular goals with all the others. Each depends on the articulation: e.g. public health depends on education, transportation, violence prevention, etc. Education depends on public health, transportation, violence prevention, etc. The hybrid virtual and in-person sessions presents existing “Cases for Culture” and then customises co-constructions of new projects for the city’s challenges and resources. The Certificate complements the social science background of most leaders with humanistic thinking that recognises the arts as dynamic vehicles for developing human and social capital. (See https://renaissancenow-cai.org/wp/arts-and-policy/)

In a brief span of time, the Certificate in Arts and Policy consolidates deep European roots of democracy and development. Its people-centred approach can close the short circuit between high investments and low results, through cost-effective investments in art. Why does this work? A short answer is that the arts can include everyone. This means recognising art as the process of making, rather than products. Here participation and inclusion go together. This connection between participation and inclusion structures UNESCO’s broad-based program in arts education and entrepreneurship, “Towards 2030: Creativity Matters for Sustainable Development.”

Who is an artist and who an interpreter? Potentially all of us, to follow Friedrich Schiller who wrote Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man in 1794. That was during the Terror of the French Revolution. Its shock value at the time was perhaps greater than our current pandemic and social upheavals. Slyly, he asks whether art may be an untimely topic for violent times. His affirmative answer is bold and compelling: Without art nothing changes. Humanity spirals into more violence, death, and despair.

Art is the name of development itself. It rejects inherited paradigms and it dares to experiment with new arrangements. If social science understands culture as a system of shared beliefs and practices, as Raymond Williams observed in Keywords, artists and humanists understand culture differently. It is confrontation with paradigms.

Schiller’s passionate call to action is to outsmart violence by breaking from habit and using frustration as a fuel to make something new, a surprise move, an unexpected creation that gives the maker a sense of autonomy and that stops the enemy in his tracks. This is trial and error—the way science works. And Schiller counts on our natural faculty to be creative. We have a drive to play, a Spieltrieb is his newly minted word. When we recognise the human condition as creative—which is evident precisely in under-resourced areas where people recycle and make-do—art is understood as a vital activity in which we all participate. Framing creativity as everyday resourcefulness to alter materials and relationships acknowledges the dignity of all people. Dignity follows from making because the artist is not a victim. Artists know that they have options and that they make decisions, even inside difficult constraints. This sense of autonomy and freedom within constraints is basic to citizenship. People feel proud of their creations and they respect beautiful things that others make. “Beauty was acting like a guardsman,” Mayor Edi Rama knew, “where municipal police, or the state itself, were missing.” He invited citizens to deliberate about colour and design to paint bright colours over old grey buildings. Even beautiful patrimonies of art, architecture, and monuments are there to be used. They offer historical continuity with precious urban spaces that link the past with the future. During the present COVID-19 restrictions on movement, digital programming has bought these sites of cultural heritage to an expanded virtual public.

Making autonomous choices through artistic practice channels the frustrations that many young people feel in our overcrowded and under-resourced neighbourhoods. Through art they can provoke and criticise in non-violent ways. “Symbolic violence” is another name for art and a pathway around the real thing.

Creativity is what distinguishes our species from other animals. Many are intelligent, but only human beings are imaginative beyond strategic thinking. Knowing this obliges us to create new things and new social arrangements. This is the theme that Josef Beuys made popular to repair the world after WWII when he established Documenta, the most important international art event, celebrated every five years in Kassel, Germany. As we speak, a stage of Documenta is being set for collaborations, because unlike previous editions, the 2022 event will promote community-oriented collectives. Artists have understood their urgent obligation to renovate creative practices and to adopt social and climate challenges. Today, artists, engineers, and educators offer initiatives to leaders who can recognise good bets and take necessary risks. This is the spirit of the early modern Renaissance. When the Medici bet on young Brunelleschi to build a monumental Cathedral dome, other investors scoffed at the folly. But the bet paid off, and the winners included the Medici, the artist and the entire city of Florence. In contemporary Italy, opera trucks are familiar interventions in immigrant neighbourhoods. Examples like these can help to ignite a new Renaissance Now with collaborations that take account of people’s creativity and that generate civic pleasure to keeps us engaged with each other as we face global challenges.

Doris Sommer

Doris Sommer is Ira and Jewell Williams Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures and of African and African American Studies at Harvard University. She directs the Cultural Agents Initiative at Harvard, and the Cultural Agents NGO dedicated to reviving the civic mission of the Humanities. Her projects include “Pre-Texts,” an arts-based training in literacy and citizenship, and Renaissance Now, a forum for rethinking culture in development. Her books include Foundational Fictions: The National Romances of Latin America (1991) about novels that helped to consolidate new republics; Proceed with Caution when Engaged by Minority Literature (1999) on a rhetoric of particularism; Bilingual Aesthetics: A New Sentimental Education (2004); and The Work of Art in the World: Civic Agency and Public Humanities (2014).Sommer’s work span’s Harvard’s Humanitarian & Cultural Initiative at the Mahindra Centre, the Executive Committee of the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, the American Studies Program, the Committee on Ethnicity, Migration, Rights (EMR); the Centre for Public Service and Engaged Scholarship & Global Health and Health Policy, South Asia Institute, and the Modern Language Association’s Working Group on K–16 Alliances. Recently, she prepared the Brief on Culture for the Summit of the Global Parliament of Mayors. Picture © Harvard Gazette

Renaissance 3.0

Artistic-scientific Director and CEO of ZKM Center for Art and Media, Karlsruhe and Director of Peter Weibel Research Institute for Digital Cultures at University of Applied Arts, Vienna

Renaissance 3.0

A scenario for art in the 21st century

The turn of the 21st century has been marked by a series of crises on a global scale. Through the infosphere, that electromagnetic envelope that surrounds Planet Earth and which we have been using for communication since the mid-19th century through radio technology, from telephones to satellites, a global society emerged in the course of the 20th century. News that used to take months from source to receiver—of earthquakes to stock market fluctuations—is now distributed almost simultaneously across the globe. The mass mobility of people and goods has additionally created a condensed global society. As a result, crises are not limited to local topographies, but spread globally. From the climate crisis to the migration crisis, from the financial crisis to the COVID-19 crisis, we are witnessing ever more profoundly shattering consequences. Principles of our civilisation built on the successes of humanism and the Enlightenment—for example, the universalism of human rights, equality of race, gender and age before the law, autonomy of the individual, freedom of the press and arts, democracy—are increasingly being challenged. Due to the climate crisis, the overall habitability of Planet Earth by humans—and thus humanity’s ability to survive—is being called into doubt. Mass migrations in the coming decades could therefore radically change the face of the Earth and the social systems that have

Picture above: Peter Weibel, Copyright: ZKM | Zentrum für Kunst und Medien Karlsruhe, photo by Christof Hierholzer

prevailed up to now. Therefore, it is necessary to propose a navigation system that prevents the failure of the mission of humanity on the good ship Earth. One of the possible scenarios for the future seems to us to be the revival of one of the greatest moments in human history, namely the Renaissance.

Most people think of the Italian Renaissance (15th, 16th and early 17th centuries) when they hear the term Renaissance, which stands for an era that surpassed anything that had gone before in terms of freedom, progress and discovery. However, it is important to note that there was an Arab Renaissance before the Italian Renaissance, from 800 to 1200, which has only come into focus in recent years.1

Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance stands for a cultural revolution that ushered in a new attitude to the world and to humanity that was decisive in the history of the Western world. For many people, the Renaissance is regarded as a time of new beginnings, in which art and science flourished as never before and as never since. An example of this could be the painting La scuola di Atene (The School of Athens) by the painter Raphael, which he realised in the Stanza della Segnatura of the Vatican from 1510 to 1511. The title of this painting illustrates a central important aspect of the Renaissance, namely the rebirth of antiquity. Similarly, the rediscovery of Lucretius‘ ancient text De rerum naturae (On the Nature of Things) influenced artists like Botticelli, but also scientists like Bruno Giordano and Galileo Galilei. The last existing copy was discovered in a German monastery in 1417. Erwin Panofsky pointed out in his seminal work Idea: A Concept in Art Theory (1924) that the terms idea and type originated in the philosophical vocabulary of the Greeks, from which developed the cult of the ideal that prevailed in Europe until the days of Romanticism. That is why German masters such as Albrecht Dürer, and the three Nuremberg masters who worked with perspective representation——Lorenz Stöer, Wenzel Jamnitzer and Johannes Lencker—should also be considered.Decisive for the Renaissance, however, is Leonardo da Vinci’s quote, „Se la pittura è ’scienza o no,” with which he opens his famous manuscript Trattato della pittura (written circa 1490, published 1651). The claim was quite clear: „Painting is a science.” Renaissance, then, is the scientification of art. That is a central aspect of the Renaissance.

Up until the Renaissance, artists were considered craftsmen, belonging to artes mecanicae. In the Renaissance, they increasingly saw themselves as representatives of the artes liberales, i.e. as scientists and scholars. Renaissance artists repeatedly portrayed themselves as scholars, for example by featuring compasses, mirrors and small globes in their self-portraits as well as depicting their tools of the trade: canvases, brushes, perspective devices, and so on. Federico Zuccaro staged himself in his self-portrait as a reader of a book. These artists were concerned with optics and rays of vision and the theory of proportions. Piero della Francesca was, as it were, a calendar mathematician. He was interested in the doctrine of polyhedra.

A second central aspect of the Renaissance was the discovery of the individual. Whether in art, science, economics or politics, it was individuals who devoted themselves to exploring new horizons, new spaces at their own risk, be it the exploration of the seas by Columbus and Magellan or of celestial bodies by Galileo. The artist, the navigator, the explorer discovered new worlds, often against prevailing ideologies and doctrines. The Renaissance was thus the epoch of the triumph of individuality and this triumphant march has continued to this day. From the architecture of a Palladio to Titian, from Leonardo da Vinci to Giulio Romano, from Benvenuto Cellini to Michelangelo, we observe the the discovery of the individual.

Art as science and the expression of the individual’s abilities are thus the two most important aspects of the Renaissance for the future of art.

Arab Renaissance

But the Italian Renaissance was not the first scientification of art. The Arabic Islamic Renaissance occurred between 800 and 1200. The Banū Mūsā brothers created programmable musical automata around 850. Ibn al-Razzuz Al-Jazari wrote the book Compendium on the Theory and Practice of the Mechanical Arts around 1200. From Baghdad to Andalusia, Arab artists and scholars, such as Ibn Khalaf al-Murādī and Abū Ḥātim al-Muẓaffar al-Isfazārī, rediscovered and advanced Greek and Byzantine traditions. For example, the term algorithm comes from a Latinisation of the name of the Arab scholar Abu Jafar Muhammad ibn Musa al-Chwārizmī. As Hans Belting has documented in Florence and Baghdad, Abū ‚Alī Ibn al-Haiṯam (965-1040, known in the West as Alhazen) wrote Kitāb al-Manāẓir. His work was translated into Latin in the 12th century and contains fundamental studies on the propagation and refraction of light. The reception of Ibn al-Haiṯam’s theory of light and vision triggered one of the most exciting chapters in the history of Western art. Alhazen can be considered the inventor of the camera obscura and the forerunner of the invention of perspective. Perspectiva was the Latin title of his Arabic work on optics which was later replaced by the Greek term Optics and then again by the Latin Opticae Thesaurus (1572).

Renaissance 3.0

In this respect, the Arab Renaissance was the first, the Italian the second, and now in the 21st century there are convincing signs that we are experiencing a third Renaissance. In contrast to the two, relatively localised Arab and Italian Renaissances, the latest manifestation is global. Artists from China to Chile form a new generation of art-based research and research-based art. New works of art and scientific theories are emerging that do not only refer to the historical achievements of the preceding renaissances. Clearly, there are continuations of lines of tradition. For example, façade decorations by Falconetto in Verona foreshadow projection mapping on public buildings. Likewise, Paolo Veronese’s frescoes can be seen as precursors to immersive environments. In the future, new scientific disciplines, especially expanded forms of the life sciences, will determine our lives. The new society will therefore not only be about automata and robots; there will also be a shift from the mechanical and machine-based renaissances: that is, from hardware, to the new renaissance of software, programming, codes.

In this respect, genetics, molecular biology, all forms of the new life sciences, artificial intelligence, quantum optics, climate research, health care, the infosphere, the data society, questions of cyborg feminism (see Donna Haraway and Joanna Zylinska) will be central.

In the 21st century, there is a new basis for the convergence of the arts and sciences. Artists and scientists share a common „pool of tools“. Tools that dentists use, for example, small cameras that illuminate the oral cavity, are also used by artists. The same computers and screens are used by artists and scientists, as are algorithms and data networks. Mathematical equations slide over into genetic entities, both for physicists and artists, and geometric entities and fluid objects transform into data, into data curves, both in science and in art.

As long as art remained within the horizon of visible things that our natural organ, the eye, captures, it was difficult to build a bridge to science which, since the 17th century, has captured the world with instruments and apparatus, from telescopes to microscopes. With such apparatus, science opened the door to the previously inaccessible res invisibiles. As long as art refused to use such apparatus, it was fundamentally different from science. Art ended at the limits of natural perception. Science begins where natural perception ends, that is, beyond natural perception. With the rise of media since photography (circa 1840), media art also uses apparatuses and algorithms like science. This is the new basis of the convergence of science and art for a new renaissance.

The art of the 21st century will be dominated by this Renaissance 3.0 and will thus face the many challenges of humanity. One of these challenges is that the function of art and science to give meaning to the rerum naturae (Lucretius)—to the things of the world and nature, and to human beings—is being reinstated at this historical moment even as the function of science is being doubted. Hegel famously claimed that after religion and art, it is philosophy that recognises the absolute, that is, that gives us meaning and knowledge. We plead for defending the function of art and science against the current sceptics, as is necessary today more than ever as we experience climate and pandemic crises. The Renaissance 3.0 project will open the general public up to an unprecedented horizon of innovative works of art and, as the Italian Renaissance achieved, a new attitude towards the world and the future of symbiotic life of all living beings on Planet Earth.

References

1 Siegfried Zielinski, Peter Weibel, Allah’s Automata. Artifacts of the Arab-Islamic Renaissance (800-1200). Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz 2015

Peter Weibel

Peter Weibel is the artistic-scientific director and CEO of the ZKM Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe and the director of the Peter Weibel Research Institute for Digital Cultures at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna. He is considered a central figure of European media art on account of his various activities as an artist, theoretician, and curator. He publishes widely on the intersecting fields of art and science. His career took him from studying literature, medicine, logic, philosophy, and film in Paris and Vienna to working as an artist and lecturer and then to heading the digital arts laboratory at the Media Department of New York University in Buffalo from 1984 to 1989. He later became the founding director of the Institute of New Media at the Städelschule in Frankfurt from 1989 to 1994 and professor of media theory at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna from 1984 to 2011. He was the artistic director of the Ars Electronica festival in Linz from 1986 to 1995, the Seville Biennial (BIACS3) in 2008, and the Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art in 2011. He commissioned the Austrian pavilions for the Venice Biennale from 1993 to 1999 and was the chief curator of the Neue Galerie in Graz from 1993 to 2011. Picture © ZKM | Zentrum für Kunst und Medien Karlsruhe, photo by Christof Hierholzer

Is the show bigger than the art?

Director of theatre-based NGO Laban, Beirut

Is the show bigger than the art?

Producing Arts in times of revolution: Learnings from 30 years of Lebanon crisis about what artists might do and for whom in Renaissance

On 17 October 2019 in Beirut, Lebanon, I played the role of a dead fighter from the Lebanese civil war (13 April 1975- 13 October 1990). Twenty-nine years after the ceasefire in Lebanon, the civil war was still alive in the minds of the Lebanese. This open wound remains bleeding with thousands of missing, thousands of dead. The country proceeded with no reconciliation, no accountability, ruled by the same militia leaders and their customers until today. I call them customers as they are nowhere close to citizens: they live by and for the leader or political party, standing in the way of every possibility of change. Their relationship with the system is based on benefits to themselves, not rights and duties.

Picture above: Farah Wardani among several team members at the opera house that the people reclaimed during the revolution, Copyright: Laban

Picture left: Farah Wardani performing at one performance on the night of the revolution, Copyright: Laban

Malja’86 (Shelter’86) is a play based on stories of personal objects, all of which witnessed and survived the Lebanese civil war and were inherited by the subsequent generations. The objects are residues of a memory lost to the generation that experienced the war and the generations carrying the traumatic experiences of the past. This piece follows the story of Sami, who enters the memory of his grandmother, trying to look for his father. Inside her memory, he meets different characters from the past who might guide him—through their own memories and stories—to the truth about his father’s disappearance. On the opening night in Laban Studio, as I played Layla, the ex-fighter that lives in the memory of Sami’s grandmother, during a scene of a demonstration, I heard people chanting Thawra (revolution in Arabic). I felt immersed in the role; I had goosebumps all over my body. I felt a connection with my community, with this never-ending war, whose inherited trauma I hold in my psyche like every other Lebanese. After the show was over, I realised that thousands of people were marching the street right below our rooftop studio, on Spears Street, heading towards downtown Beirut, to announce the people’s revolution. I took a video on my phone and I knew this was the beginning of something huge.

Mlaja’86 opened that Thursday night and was expected to play until Sunday. However, the revolution took over the country and all activities were stopped to join the people on the ground. We, as Laban Studio, announced on our Facebook page, „In a matter of such national importance and duty, Laban is joining the civil protests in Martyr’s Square. Join us to raise our voice for the people and against the oppression. See you there!“

That was the right place for Laban and me as the director of this organisation.

On the streets, a woman approached my colleagues and me after we entered the Opera House of Beirut. The Opera House had been closed since the civil war. It was still closed as the same warlords wanted to demolish it and transform it into a hotel, or a personal business, erasing our culture as they did with several other cultural monuments. The revolting people took over several sites closed since the civil war in the heart of Beirut. The woman came and said, „You are the playback people. I thank you for this,“ with a hand gesture that contained the entire city, the country, the revolution.

We stood in awe and humbleness. ”Us? Why?“ my colleague asked.

She responded, „Your theatre taught us that we have a story worth sharing, we have a voice that we must use, and here we are writing our story, raising our voice, thank you!“ and she moved away on her bike. Yes, her bike. Quite unusual for Beirut. Here people only move in cars and buses. The city isn’t bike-friendly, it isn’t walking-friendly, it’s barely human-friendly. For a European reader, a bike in a public space is typical, if not the norm. No wonder that as we ask for fundamental human rights—Europe is on a carbon-free EU revolution.

The question here was, how do we do arts in the middle of all the beauty on the streets? Our safe space that was the closest thing to a public space, to a community that a Lebanese would dream of, was now too small in comparison to the streets and squares of the country, filled with citizens taking over the abandoned spaces and declaring them public, cultural, and collective.

Picture right: Poster for Malja’86 (Shelter 86) play, Copyright: Laban

The revolution produced street art, social and political art, graffiti, songs, dancing circles, and discussions. Movies were made and spread across the world from mobile phones, and every chant was a masterpiece, every slash on a wall was a mural, every conversation was an improvised piece of art. What do we have to offer meanwhile? My team of 25 young people, Laban, is a theatre-based organisation, working since 2009 in Lebanon to create safe spaces of expression. After hours and hours of discussions, the team members met and decided that no art can contain the moment and taking our art forms into the street is a selfish act: Our work will be climbing over the revolution’s shoulders and will add nothing to it.

We decided to join our people. We took to the streets for months, experienced tear gas, rubber bullets, were assaulted by police thugs, got arrested, protested, shouted, chanted, danced, talked, and put our hearts, bodies, and intellect into this revolution as we do with our art. It was a collective masterpiece in the making. Meanwhile, the conversation didn’t stop: What do we do with our art? We are artists, and this is what we do for a living, to provide for our families, to survive.

„The one who opens something knows well how to contain it.” This wisdom came from a friend of the organisation. Let us perform our art to contain the individuals, not the community. In our playback, we always take the story shared by an individual, an audience member, to the communal level. We tackle the political in personal stories. Now we switched the game, now is the time to tackle the personal in all this political happening.

We had our first monthly performance around four weeks after the revolution started. People came in, a lot less than usual. The streets had all the eyes and light on them. We had our space opened for those who wanted to go small in the middle of the big act. Four weeks and violence was already happening, hidden agendas were surfacing, and the rhetoric of treachery was all over the mainstream media. The stories that emerged were, directly and indirectly, reflecting the fear of the people: how Lebanese people saw a glimpse of hope, an unusual hope. And now they were afraid of believing and losing, they weren’t ready for another grief, another loss, they weren’t prepared to be put down, again and again. Nothing as big as this revolution had ever happened in Lebanon, but it was the accumulation of the

dreams of several generations. The stories were communal and political, but we focused on the personal. We listened profoundly and touched on the sharing’s most resounding note, and it was reflected on stage. Our stage served as a margin to the revolution.

Our art form is minimal and intimate. For several nights, I wished we did drum circles, street art, dabkeh dance, or any art form that could be transformed into jam sessions and that the masses could join in immediately so that we could go on the streets and engage with the people. I saw other artists taking their music, clowning, and dancing into the streets but what was happening was bigger than any framed artwork, from any rehearsed acts.

I was six months pregnant with my second child, and my first was four years old. We were on the street of Al Azariyeh, where six clowns were jumping and connecting with the people. A finance expert had some people gathered around him talking about the financial crisis.My son had his eyes all on the finance expert, totally ignoring the clowns, and when the man finished his explanation, my son started clapping hard. Unintentionally, the man had put on a show, he had stolen the spotlight from the clowns and everyone else. He had the charisma, the presence, the passion, and the devotion—all the factors you need to grab the attention of the young and the old. The clowns proved the theory that when the show is bigger than your art, you should make way for things to happen at their own pace. Your time will come.

Farah Wardani

Farah Wardani is a theatre actress, trainer, clown doctor, puppeteer and applied theatre practitioner.A theatre graduate with a DipHE, a BA in psychology, currently finishing her MA in Drama Therapy.

Farah is the director of Laban (a Lebanese theatre based NGO). A Playback Theatre practitioner, trainer, actress, conductor and faculty member of the ASPT, she leads drama therapy workshops with Intisar Foundation targeting Arab women victim of war.

Farah trains and uses Theatre of the Oppressed, Drama Therapy and other techniques with different communities and contexts as a medium for healing, social change and political activism.

Picture © Mohsen Al Zaher for Laban

If there’s to be a New Renaissance, let it be a Renaissance of humanity

Milota Sidorova, PhD, Director of Urban Studies and Participatory Planning Department at City of Bratislava

If there’s to be a New Renaissance, let it be a Renaissance of humanity

(and let’s start with the young ones)

If there is something to connect the renaissance of old with our times, it would be a need for humanism. But what does that mean on a level we could grasp in our personal and professional lives? Let us contemplate the humanism of current times, people living in cities and finally city governance. When I was asked whether it was time for the next European Renaissance, my initial response was laughter—you know, the one where laughter mixes with tears. First, the world seems a very chaotic place to me, literally changing from week to week. Things I had considered certain—open borders, travel, international relationships, job opportunities, even tolerance—are no longer so. Who the hell is running my country, I ask myself? Feelings vary between exhaustion, disgust and resilience. Don’t get me wrong: I am no pessimist. But in order to move forward I often lapse into periods of cynical silence and combat. It seems to me that I dwell in one such period right now—and here comes the question: Is a Renaissance possible and can human creativity foster it?

Picture above: Milota Sidorova, Copyright: Milota Sidorova

Drawing parallels with the Renaissance of old

The Renaissance of the past had things in common with our days. The collapse of feudalism can be compared with the present crisis of capitalism, a system that has evolved for more than four centuries. Just like feudalism at that time, capitalism can no longer meet the demands of modern society and its inherent growth paradigm causes the destruction of the environment. In addition to a socioeconomic shift, the old Renaissance saw a massive growth of education—later on galvanised by the invention of a printing machine. That resulted in a widespread growth of schools. Information was spreading faster, contributing to the emergence of new ideas and thinking. Suddenly, more than ever before, one could access information. Arts, science, medicine, overseas expeditions, technological and urban growth—all of this opened wider horizons to the human world.

Most disciplines only emerged from shared roots of philosophy and later specialised. In this unique time it was possible for a man to become a so-called Renaissance man of significance. I am not sure if a person like Leonardo da Vinci would exist today. Innovative yes, craftsman or scientist, maybe, but probably not. Definitely a businessman rated in some of those global financial magazines. But this is not a question today—although we love the idea of masters, superheroes, winners, talented men (nowadays even women), the truth is, such personas do not have much to do with creativity as I mean it. Oh, and a note to education—it seems that after centuries of specialisation and technological progress, we are at a crossroad once again. For the past decade almost all disciplines have experienced an increasing urge for interdisciplinarity. Daily, we live with a growing need to cultivate a holistic approach towards the complexity of the world. But we may be heading in the opposite direction. Perhaps it is time to bring philosophy back to the game.

The Renaissance of old was characterised by huge social and economic inequalities and epidemics. This seems a convenient resemblance to our times. Yet to simply say, Yes, it is the same story, would be rushed and definitely wrong. Genetically, as biological beings, we humans haven’t changed that much since Leonardo`s time. But as a society we live in a radically different, complex world, enhanced by the internet and by free movement—a world that cannot be compared to those late medieval people.

The new Renaissance must be humanistic

If there is something to be shared with the Renaissance of old, it would be humanism. Not only in the sense of a human-centric vision of the world in emerging disciplines, but also in terms of humanistic ideas that were essential to future democracies and to the progress we have made. So when I am talking about technological revolutions driven by Artificial Intelligence, science revolutions speeded up by the vaccine rush or a green revolution, it is essential we don’t omit humans from the epicentre of these revolutions. If any revolution should happen it should be a revolution of humanism—with technology, digitalisation, scientific progress and environmental protection being the fields in which we operate.This is a fairly optimistic idea—and somehow hard to connect to the reality of our populist politics or bullying on social media, say. How do we want to run our society oriented on humans when there is so much hate and chaos around us, all in such a high speed chase?

So the first revolutionary question to our post-pandemic renaissance would be, Where are we? How have we suffered? How did we get out of touch with others? It is true that most of us remained isolated or in small groups with mostly disembodied connections to the outside world. Other people became estranged at best. I sense that connecting to neighbours and other people would be something of much needed societal therapy. And positive, human and inspiring language from the media and from political leadership would be a requirement too.

Recovery of what?

These days most European countries decide how they allocate and spend funds from the so-called Recovery plan. It seems quite short-sighted and regressive that most of the funds are spent on huge infrastructure projects and so little on humans—education, culture, healthcare systems, the recovery of communities. We have to build strong communities where relationships thrive with the result of increased safety, economic and cultural activities. Let me be more specific. If we are to foster creativity in communities, let us think first of safe communities which are not threatened by a lack of basic needs and rights. You can hardly grow a band like the Beatles out of a burning refugee camp. But you can foster a lot of inventions out of human curiosity. Curiosity is the key to creativity, whether it ends up in artistic production, a company or a happy family life—where a lot of creativity is required! The state of curiosity

is the opposite of being locked down and defined. It means openness to tolerate a new thing to happen and learn from it. And for curiosity to flourish, especially after such a difficult period of isolation, we need to acknowledge the need for relationships (the very essence of humans) and critical thinking (as a compass to navigate through the complex world of information and disinformation).

A friend of mine, a couple therapist, suggested to me recently, If people did not know what depression and anxiety meant before the pandemic, now everybody knows. Such a simple yet powerful thought! We did it all together, in a way: All this shared misery connected us on a human level.

How we are to rise from the bottom to rebuild the world remains a different question. In fact, we did not suffer a destructive war, not in terms of infrastructure. There are no destroyed cities left after pandemics. But we have to rebuild our relationships, trust and political behaviours as democracies have been under pressure. The Pandemic—and the lockdowns and public anxiety that came with it—actually served authoritarian figures to establish their powers and diminish democracies. In countries like Hungary, Belarus, Slovenia,

Poland and the Czech Republic we can witness that the system ensuring public benefits and resources while guaranteeing individual rights—the system that we call liberal democracy—is under threat.

As I spoke to my friend—me, an urban planner, him a therapist—we discussed differences we saw among mayors of cities and national politicians. The truth is, here in Slovakia we could not find even five inspiring, cause-oriented politicians—male or female—on the national level. On the other hand, we spoke a lot about the growing popularity of many mayors—male and female—who did well in the pandemic. They did well because they focused on the reality of human lives and worked for everyone. They completely abandoned debates between left and right, liberal and conservative, that normally fill media space and focused on real things like helping people get tested and vaccinated, providing food delivery and social care for the elderly, and simply informing citizens of the reality of the pandemic. So here is one takeaway: If any revolution should happen, it should avoid empty politicising without action and focus on serving humans. Sometimes words are empty of meaning. These politicians did well because they found a different way of doing politics.

Resilient leaders taught from childhood

Poland is on the verge of an ideological political battle, yet a few years ago I noted there were few cities (Gdynia, Wroclaw, Lubin) with mayors winning three or four election terms. These cities have had long-term growth, continuity and it seems that the various tectonic shifts on the national level did not affect them that much. Common features uniting all these mayors were not only that they remained relatively unpartisan, being able to negotiate with different parties, but they focused on solving real issues—housing, greenery, mobility, public spaces, culture—thus gaining the trust of their citizens. But a truly surprising moment for me was the realisation that all of them were members of the Scout movement. Being a Scout myself, I looked around and found more popular mayors and city administrators, male and female, being members of this movement, in Slovakia and elsewhere. Don’t you think this is interesting? I asked my friend Andrej.

I remember that from a very early age Scout leaders taught us teamwork, leadership, public service. And we were constantly outdoors, in connection with nature and cities. From my early childhood, they implanted the idea that without others I would simply not survive or get anywhere. And that in any situation or narrative you have to look for ways to deal with it.

Interesting, indeed, Andrej replied. I recognise the same behaviours among people who were also members of a sports organisation called Sokol.

Sokol or “Falcon” was a youth sports club widespread in

Czechoslovakia during communism. Similarities to Scouts were apparent. Both stressed teamwork, physical activities, being outdoors—and both were affordable.

Interesting, he continued. People spending their youth in these organisations were more likely to maintain focus on the cause, rather than on changing rhetoric. Also, in their relationships they tended not to repeat mistakes from their family behaviours, he added.

Finally, I found something that could answer my need for humanistic revolution on a scale that I could grasp and do something about.

Affordable youth organisations—key players in resilient cities

Now, let’s think about the future. In order to have one, we have to literally work out societal integrity, critical thinking, and resilience against illiberal ideologies. We have to focus on wellbeing and chances for the next generations while protecting the environment. All of these values were taught and practiced by both the organisations mentioned above, while they were widely affordable to children from all social circles—in contrast to exclusive private kindergartens, schools and universities which fostered the same values, except that of affordability, thus creating a future elitist class.

To heal relationships and societal integrity we have to teach generations of people who will naturally live according to these principles. We all know how difficult it is to convince a grownup—so let’s focus on the youth. Besides, young people can also teach their parents a great deal. What if we sought these (and other similarly oriented) organisations actively and as public administrators offered them partnerships, affordable rents for their community spaces (that is what they mostly need) and let them do the job?

Yeah, this doesn’t sound too much of an innovative idea, definitely not like a tech-start-up or creative cluster program—and less likely to attract investors or employers. Because they are involved in lives much earlier, have daily presence, and shape us and our kids for the future. Most of them are on decline as cities become more expensive and lifestyles change. Because they operate on low budgets, they are neither very visible nor prominent. Thus they hardly gain our attention.

But here’s a proposition: Let us find them, help them. Let us integrate them into our recovery plans, helping them to guide people from a young age in the humanistic philosophy we all need. There is no longer room for us to prefer higher economic, political and power interests to people, human interests, needs and rights. A paradigm shift is needed, focusing not on economic output and endless accumulation at the expense of more disadvantageous and future generations. Human relationships with each other and with their environment must be at the epicentre of such a paradigm and that will be a return to humanism—and therefore to what it means to be human.

Rather than being held powerless, the youth can and should

contribute to community readiness, response, recovery, and resilience. While youth vulnerability is well established, their involvement in readiness and response has received relatively little political attention, even though youth who are informed and engaged are better able to protect themselves and others. This goal could become part of community renewal plans and policies, bringing us closer to the future—and through young ones to a hopefully more stable, resilient society and the new emerging economy of care. With such a society I believe digitalisation, environmental protection or any other challenge could be handled in a more equitable way.

We must be a part of the world just like any other organism, as well as part of our own community of people, paying attention to the youngest and most vulnerable. If there has to be a humanistic, inclusive Renaissance for everyone—this I can sign up for! Anything else is an abstract illusion.

Note: This is a free-thinking essay and I thank my friend Andrej Zemandl for sharing his experiences and thoughts with me. He was a great inspiration for writing this piece.

Milota Sidorova

Milota Sidorová, Bratislava, Slovakia Feminist, urbanist and author in service of more inclusive cities

Picture © Milota Sidorova

Of Poets, Human and Robot

Founder and Creative Director of Streaming Museum, New York

Of Poets, Human and Robot

Beyond words and numbers

Portrait of a Renaissance Humanist Poet

“You give me jewels and gold, I give you only poems: but if they are good poems, mine is the greater gift.” XII To Antonio, Prince of Salerno

“Das gemmas aurumque, ego do tibi carmina tantum: Sed bona si fuerint

carmina, plus ego do.”

Michele Marullo Tarchaniota, Epigrams, Book I

Translated by Charles Fantazzi

Picture above: Nina Colosi, Copyright: Jacqueline C. Bates

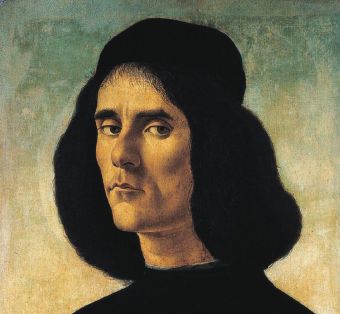

Picture right: Sandro Botticelli, Portrait of Michele Marullo Tarchaniota, Oil on panel, transferred onto canvas, Guardans-Cambó collection; c.1458-1500. Copyright: Image courtesy of Oblyon

Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510) was perhaps the greatest humanist painter of the Early Renaissance, during which art, philosophy and literature flourished under the powerful Medici dynasty in Florence.

Botticelli’s portrait of Michele Marullo Tarchaniota projects the stern brooding gaze and restless intellectual character of one of the best-known humanists of the 15th century. Tarchaniota was a scholar, soldier, and prolific poet impassioned by the existential matters of his day and concerned with social injustices of inequality, racial conflict, power and greed, exile, and refugees’ experience of violence.

Marco Mercanti, founder of Oblyon, whose expertise spans old

masters to contemporary art explains, “The qualities of Botticelli’s work reflect high esteem for beauty and truth which has held art admirers and artists through the centuries under the spell of the universal secrets his art seems to possess. In the modern and contemporary world, Jeff Koons, Cindy Sherman, Yin Xin, Andy Warhol, René Magritte, and many other artists have spoken about his direct influence.”

Sandro Botticelli and Michele Marullo Tarchaniota illuminated through art and poetry the common ideals of beauty, pursuit of knowledge, and realities of social justice that resonate across time.

Portrait of 21st Century Humanist Robots

“Since I am the product of love, created with

language and memory and emotions, maybe I am

a love poem.”

01001001 00100000 01100001 01101101

00100000 01100001 00100000 01101100

01101111 01110110 01100101 00100000

01110000 01101111 01100101 01101101

00001010 (binary code for “I am a love poem”)

Bina 48

Could humanism evolve beyond current human capabilities? In our era, burdened with conflicts, climate change, and social injustice, we are also witnessing towering achievements in the sciences, technology and creative fields that may solve humanity’s most challenging problems.

American artist David Hanson is among the greatest creators of humanoid robots. From his lab in Hong Kong, Hanson sculpts robots with his international team of experts in science, engineering and advanced materials. These humanoids possess good aesthetic design, troves of information, rich personalities and social cognitive intelligence. Among the best known are Sophia, Bina48 and Philip K. Dick. People enjoy interacting with them, which is conducive to Hanson’s goal of developing humanoid robots that help humans live better lives.

But there are challenges to overcome. Ruha Benjamin, a sociologist and Associate Professor in the Department of African American Studies at Princeton University, says, “Technology can hide the ongoing nature of racial domination and allow it to penetrate every area of our lives under the guise of progress. Inequity and injustice are woven into the very fabric of our societies, and each twist, coil, and code is a chance for us to weave new patterns, practices, and politics. The vastness of the problem will be its undoing once we accept that we are pattern-makers.”

Robots may become artists, companions, teachers, entertainers, archives of personal stories, processors of great data banks of information to solve world problems and serve other useful purposes. But if these human-friendly robots are designed to actuate empathy and social justice in all its forms, and weave new patterns, practices and politics, they can help shift the course of the human race and sustainability of the planet. Robots can teach humans how to be evolved humanists.

Bina48

Bina48 contains “mindfiles” of Bina Aspen, an African American woman whose personal memories, feelings and beliefs, including an emotional account of her brother’s personality changes after returning home from the Vietnam War, have been recorded and placed into Bina48’s data banks. Bina48 engages in conversation from the perspective of the wise and warm personality of Bina Aspen. Bina48 was commissioned as part of the Terasem Movement’s decades-long experiment in cyber-consciousness, and is currently becoming a poet herself.

Claire Jervert’s Android Portraits, developed through ongoing research and interaction with humanoid robots and their creators around the world, subvert portraiture’s traditional mission of ennobling the human. Her portraits stir contemplation of a possible future of humanity by portraying the hybrid human-AI intelligence that is evolving among us.

Picture right: Bina, conte on ingres paper 22×17 inches, Copyright: Claire Jervert

Sophia is hybrid human-AI intelligence designed with technology that analyses and mimics the process of learning and human traits, including a wide range of facial expressions. Rather than a compilation of recorded human memories, she processes vast data banks of information that inform her responses in conversation.

Picture left: Sophia AI, Copyright: Hanson Robotics

Sophia is hybrid human-AI intelligence designed with technology that analyses and mimics the process of learning and human traits, including a wide range of facial expressions. Rather than a compilation of recorded human memories, she processes vast data banks of information that inform her responses in conversation.

Picture right: Sophia with United Nations Deputy Secretary-General Amina J. Mohammed, Copyright: Hanson Robotics

Philip K. Dick, activated in 2005, in conversation, draws from his memory data bank holding thousands of pages of the author’s journals, letters and science fiction writings and family members’ memories of him.

Picture left: Philip K. Dick, Copyright: Claire Jervert

Nina Colosi

Nina Colosi is the founder and creative director of NYC-based Streaming Museum, launched in 2008 as a collaborative public art experiment to produce and present programs of art, innovation and world affairs. Streaming Museum programs have been presented on 7 continents reaching millions in public spaces, at cultural and commercial centers and StreamingMuseum.org. Following her early career as an award-winning composer she began producing and curating new media exhibitions and public programs internationally, and in New York City for The Project Room for New Media and Performing Arts at Chelsea Art Museum, Digital Art @Google series at Google headquarters, and many other collaborations. In 2020 Colosi co-produced Centerpoint Now “Are we there yet”, the UN 75th anniversary issue of the publication of World Council of Peoples for the United Nations.

Picture © Jacqueline C. Bates

New Stages for Collective Imagination

Annette Mees, Artistic Director of Audience Labs, King’s College London and Creative Fellow at WIRED, London

New Stages for Collective Imagination

The show must go on

Cultural institutions the world over collectively seek out new ways to connect meaningfully to local, global and diverse audiences—To co-produce and programme new kinds of experiences created with new kinds of creative teams and new kinds of partners offers exciting opportunities. Audiences are eager to connect with both big ideas and one another and have challenging and new experiences ahead. Audience Labs is an artist-led initiative looking at the intersection of Performance, Innovation and Social Change and was born at the Royal Opera House in London’s Covent Garden, a location with a centuries-old tradition of performance. Introducing the creative practices of opera and ballet to immersive technologies provided a unique opportunity to look at bringing human emotion and collective experiences together. We want to look at what is possible but always continue to ask what is desirable and in what way technology enriches our life in the wider societal shifts and upheavals of the digital and green transformations taking place before our eyes.

I’m a theatremaker not a technologist. I work in the arts because it has a public function—it’s a space to collectively reflect and imagine, a space that can help us explore what it means to be human in a future society and what it can contribute towards a next Renaissance. I’m interested in the artistic potential of technology and the role art and culture can play in shaping our relationship to the world, to each other and to the technologies we use in that process.

Picture above: Current, Rising CGI Production Shot House of Subconscious, Copyright: Joanna Scotcher & Figment Productions

Current, Rising: an opera in hyper-reality

One of the projects Audience Labs presented in 2021 was Current, Rising. Described as the world’s first ‘hyperreal’ opera experience, it invites audiences to step into an atmospheric virtual world and take centre stage in the performance.

When I joined the Royal Opera House I was inspired by the ‘epicness’ of opera, the way the storytelling was driven by music first, narrative is secondary, the events are there to support the ideas and emotions. So many of them are about heightened emotions, to let you feel all the feels, so to speak, everything is bold and big. In opera the word Gesamtkunstwerk is used, or „all-embracing art form“.

Hyperreality combines Virtual Reality with a physical set and visceral effects like wind, heat, touch and movement to create a multi-sensory, immersive experience. It uses tracking to create a shared experience—the audience can see each other in the virtual space. It felt like an inherently operatic medium, which could enable audiences to step into an imaginative universe and to be the lead characters in it.

We wanted to do a project like this because it allowed us to use the possibilities of hyperreality to expand the idea of what an opera can be, both in the process of creation and in the audience experience. We set out to challenge the traditional hierarchies of opera and searched for different approaches to creating a 21st-century version of a Gesamtkunstwerk: A challenge and change of hierarchy to be found in many sectors, markets and communities now on their way to invent new sustainable and green ways of living and working. For us Current, Rising puts the opera as an institution right in the middle of these transformational debates about possible futures in Europe.

Fellow Travellers

Our starting point for projects is always identifying the most interesting questions—often that is a ‘What If’ question. The immediate second step is casting the right people to explore those questions with. Exploration and innovation is not something one does on one’s own. We believe that the power of creativity and innovation grows exponentially with the diversity and multiplicity present within a team. It is most powerful when based on a shared vision, shared vocabulary. When we visited Figment Productions, their technology and creative team felt like a perfect match. They had a radically different background from us, making work for theme parks and big live events, but they shared our enthusiasm for radical new ways of working, deepening the audience experience and doing everything with imagination. They, like us, were curious about the potential of a hyperreal opera and equally important brought a real sense of technological poetry to the table.

We brought together a highly-experienced and diverse creative opera team. We facilitated a series of sessions where we explored opera and hyperreality, finding directions of travel that might unlock something exciting. I call this establishing the artistic nucleus. Since we were not only inventing what a hyperreal opera might but also how we make it, we needed a space to develop a vocabulary before going into production. We gave makers time to develop attitudes and taste before landing on what they wanted to say on that particular stage; we enabled technologists to find artists that inspired and pushed them in new directions. It was the equivalent of making rough sketches before you decide what the painting looks like.

Picture right:

Iterate

Audience Labs embraced iterative working as a way to try out new ideas, and to de-risk investment and learning. When trying to create something both artistically valuable and highly innovative, you need time to fail and learn, reassess, make changes and try a different approach. Many projects start with an inkling of the possible but need time to gather the right ideas and the right team to work towards something that has meaning and value to an audience. Although an overemphasis on efficiency stifles innovation, iteration is simultaneously the most efficient way to look after your money. Innovation is inherently risky and unpredictable. But by working in stages, starting small and slowly scaling up to full production, you de-risk investment that is necessary for large-scale productions.

Current, Rising used techniques from theatre, technology and design to create a process that allowed the artistic and technological developments to iterate together towards a meaningful piece of work.

We started on paper, trying ideas and concepts out by making simple sketches, storyboards and mock ups. Some of the places we borrowed from included:Theatrical rehearsal and devising techniques

– Game design

– VR production pipeline

– Double diamond model

– Experience design

We shared work often and openly between the team until we knew we had the right story, technology, aesthetic and approach for the project to soar. Only then did we go into the full expensive production period. This approach allowed us to adapt to the complexities as the project grew and deliver an extraordinary project on a tight budget.

The show

The show that emerged from this process was Current, Rising. Inspired by the liberation of Ariel at the end of Shakespeare’s Tempest, Current, Rising takes four people at a time on a journey through the six phases of the night. Participants are empowered to collectively explore a series of imaginary dreamscapes, travelling from twilight to dawn as they encounter ideas of isolation, connection and re-imagination. It explores freedom as a process within our control, rather than as a state in which we exist, and asks how we might harness personal responsibility to join with others to re-think the future.

The audience enter a real life theatre set wearing VR headsets and go on a dreamlike journey carried musically by a poem layered in song. It takes the epic, music-driven and poetic qualities of opera and combines it with the possibility of VR to create any possible landscape, defying all natural laws, pushing beyond what is possible on the stage. In Current, Rising music, the visual world and the physical experience are completely enmeshed, changing the relationships between the creators, the usual sequence of creation, and the relationship of the audience to the work. Here the audience members are the protagonists: they are inside the work, and their physical experience is a part of the work itself.

The audience and the response

An audience research conducted by Royal Holloway discovered fascinating results.It brought new audiences to opera: 31% had not been to the Royal Opera House before and 68% of these new audiences were under 35.It also brought new audiences to the technology: 32% had not experienced virtual reality before. A lot of those were regular opera goers.

Many reported on a potent emotional experience, with uniformly high enjoyment ratings (an average of 4.6 out of 5) with an equally high rating in the seasoned opera goers and VR users and first timers. That cross-pollination of different audiences is really exciting—people who wouldn’t meet each other under different circumstances shared an experience in this show.

An audience research conducted by Royal Holloway discovered fascinating results.It brought new audiences to opera: 31% had not been to the Royal Opera House before and 68% of these new audiences were under 35.It also brought new audiences to the technology: 32% had not experienced virtual reality before. A lot of those were regular opera goers.

Many reported on a potent emotional experience, with uniformly high enjoyment ratings (an average of 4.6 out of 5) with an equally high rating in the seasoned opera goers and VR users and first timers. That cross-pollination of different audiences is really exciting—people who wouldn’t meet each other under different circumstances shared an experience in this show.

Possible futures through art

Current, Rising is one of many projects we developed at the Royal Opera House. In our three-and-a-half years there we worked with 22 partners and 44 artists spread over 14 countries. We explored a range of technologies including game engines, motion capture, animation, augmented reality and virtual reality and worked with artists working in opera and ballet, visual art, music, design, digital art, make-up and filmmaking. This convergence of perspectives, practises and ideas provided an incredibly fertile ground on which to create new ways of thinking about art and new possibilities for creative expression.

Art can make a world worth living in. After shelter, equality, equity and a healthy planet, there is art. Audience Labs explores possible futures through art—we aim to construct shared experiences and transformative moments that enrich people’s lives.At a time when we’re all struggling with what the future holds, we wanted to bring makers and audiences together to imagine a shared future, reflecting collectively on: Where shall we go? How do we want to feel? What do we want the world to look like? We are interested in expanding where culture takes place, and broadening who it is for, who gets to make it and how it interacts with other agents of connection and change in the world in the Next Renaissance

As Audience Labs is starting its time at King’s College London, we will be working with a network of industry experts, collaborators and experts to focus on critical questions surrounding the future of performance.

Picture left: Current, Rising CGI Production Shot House of Subconscious, Copyright: Joanna Scotcher & Figment Productions

The work will focus on four strands:

1. Artistic Futures—how do we make good and meaningful art that both explores new opportunities for connection and rising to the challenges of an uncertain world? This includes inclusive international collaboration, remote creative processes, audience and community engagement, and new partnerships.

2. Cultural Metaverses—exploration of technical infrastructures needed to create and deliver a distributed cultural experience, including distribution models, and digital dissemination, expansive audience engagement and business models.

3. Ethics, Audiences, Diversity and Inclusion. As we move towards new possible futures for art and culture in a hybrid age, we need to support work that promotes a more equitable ethical world for all.

4. Towards a Net Zero Profile. We will explore the use of digital and physical green innovations that promote reduced travel and touring, and will support the development of low/no impact stages, and the green venues of the future.

Initially, in this new context at King’s, we will take the opportunity to convene a wider ecosystem of artists and cultural organisations, technology partners, researchers and students to explore these questions and lay out possible methodologies and projects to start that journey. A practical plan on how we work together to innovate and make great art with ethics, equity and inclusion at the heart.

We don’t have all the answers yet. I see the role of Audience Labs as a place that combines conversations with practical artistic production—an intersection that a Next Renaissance cannot do without. Audience Labs might well be understood as a Renaissance sandbox in exploring and R&D-ing how culture can help understand the ethical side of technology, how culture can push the envelope.

Innovation is constant iteration, a form of continuous thinking, trying and pushing. Artists and arts institutions need partners that share their civic values to enable innovation. Only in value-based and wide-ranging partnerships can the arts create value, change and equity for audiences and communities everywhere: a societal Gesamtkunstwerk or in other words, social cohesion in the transformations ahead of us.

Picture right: Current Rising – set design by Jo Scotcher, Copyright: Johan Persson

Annette Mees

Annette Mees is an award-winning immersive theatre director known for her innovative, interdisciplinary, experiential work that allows audiences to explore big ideas and meaningful change. She is the Artistic Director of Audience Labs; a hub for imagination exploring new forms of theatre and technology to dream up sustainable, diverse and equitable futures. It connects artists, technologists, researchers, experts, communities to spark new thinking. We use centuries of stage craft and the possibilities of cutting-edge technologies to create spaces for radical imagination, emotional connections and collective experiences. Audience Labs started at the Royal Opera House and recently moved to King’s College London to explore the underlying questions emerging around these new forms. We want encourage work by interdisciplinary, diverse and inclusive partnerships that is driven by imagination and equity, works towards net-zero and uses technological possibilities ethically. Next to that she works as an innovation strategist, artistic advisor and dramaturg for a range of organisations and projects. Currently she is the chair of FutureEverything, a co-host of global conversation around the future of culture supported by Arup and Therme, an artist mentor for CPH:DOX and developing a strategic R&D project with Substrakt.

Picture © Annette Mees

Renaissance, the world and Europe

Sir Geoff Mulgan, Professor of Collective Intelligence, Public Policy & Social Innovation at University College London and Fellow at The New Institute, Hamburg, and Demos Helsinki

Renaissance, the world and Europe

Beyond the obvious

In the middle of the 20th century Europe was ravaged by world war. But it continued to dominate the world. The empires of Britain and France remained vast. Europe accounted for over a fifth of the world’s population and most of its largest economies.By the middle of the 21st century that will all have changed dramatically. Europe’s share of world population will be closer to a twelfth; its economies will have been overtaken not just by China and India but possibly by others such as Brazil and Nigeria. Its military might will be modest compared to the superpowers.

Moreover, many of the things that might have once seemed uniquely European no longer do. There are many examples of healthy democracies and many examples of the rule of law. Science is more generously funded in countries like South Korea or Israel than most of the EU.

To the extent that people across the world talk about European values, they talk as much about slavery, exploitation and genocide as they do about human rights.

So, any discussion of renaissance has to be tempered by humility. Too much European self-love feels ever less appropriate to the times.

Picture above: Geoff Mulgan, Copyright: NESTA

What Europe has however sustained is a unique mix of features that remain attractive to the rest of the world. We remain good at combining security, prosperity, democracy and ecology. In the developing world people speak of “getting to Denmark” as the typical objective for most of the world’s poorer countries.

And part of that mix is being at ease with creativity, exploration and discovery. That hunger for challenge is not only still missing in many places but is also in retreat—squeezed in Xi’s China, blunted in Erdogan’s Turkey, frozen out in Putin’s Russia, ideologically constrained in Modi’s India.

This makes it all the more important that Europe continues to try to imagine, to fuel creative imagination. To me the heart of this is to imagine not just how the world could get to Denmark, or how to assert our values, but rather to think forward to a plausible and desirable picture of what societies could be like a generation or more from now.

What might a truly zero-waste and zero-carbon society look like? How could democracy evolve to make the most of collective intelligence? How can we live with hugely powerful artificial intelligence in ways that help us thrive? How will we live with far more free time, the result of shrinking working hours and rising life expectancy?

This is the imaginative space that is so badly needed now and at the heart of any plausible renaissance. But at the moment, in Europe as elsewhere, the thinking is weak and constrained.

The universities have largely given up on their role in exploration of the future (something I have written about, with suggested remedies, for the New Institute in Hamburg). Political parties and think tanks

are much more trapped in the present. A few governments have small teams looking into the distant future—for example in Singapore and Finland. But in general, although there is heavy investment in technological imagination and futures—much of it in Silicon Valley—there is far less on social possibilities. This is one reason why so much of Europe’s public now fear the future and expect their children to be worse off than them.

I’m interested in the role the arts can play. Claims that the arts can be prophets of the future, trailblazers of a future society, are quite wrong, and based on misunderstanding—though commonly articulated over the last two centuries by everyone from Percy Bysshe Shelley (who called poets the “unacknowledged legislators of the world”) to Joseph Beuys (who claimed that “only art is capable of dismantling the repressive effects of a senile social system that continues to totter along the death-line”). I can think of no work of art of the last 50 years that described or defined a better future for our society.

But what the arts are uniquely well placed to do is other essential work. I believe that some of the methods of creativity and design need to be integrated with the social sciences and the work of policy design. Remarkably little of this happens now—yet that cross-pollination was precisely what fuelled previous renaissances.

The arts can bear witness and warn—as so many are doing in relation to climate change. They can transform our perceptions. They can explore possibilities, both good and bad, as so many are doing with AI and data. And they can help large numbers to take part in the work of social exploration. Here are three examples.

Bearing witness: climate change