Is the show bigger than the art?

Director of theatre-based NGO Laban, Beirut

Is the show bigger than the art?

Producing Arts in times of revolution: Learnings from 30 years of Lebanon crisis about what artists might do and for whom in Renaissance

On 17 October 2019 in Beirut, Lebanon, I played the role of a dead fighter from the Lebanese civil war (13 April 1975- 13 October 1990). Twenty-nine years after the ceasefire in Lebanon, the civil war was still alive in the minds of the Lebanese. This open wound remains bleeding with thousands of missing, thousands of dead. The country proceeded with no reconciliation, no accountability, ruled by the same militia leaders and their customers until today. I call them customers as they are nowhere close to citizens: they live by and for the leader or political party, standing in the way of every possibility of change. Their relationship with the system is based on benefits to themselves, not rights and duties.

Picture above: Farah Wardani among several team members at the opera house that the people reclaimed during the revolution, Copyright: Laban

Picture left: Farah Wardani performing at one performance on the night of the revolution, Copyright: Laban

Malja’86 (Shelter’86) is a play based on stories of personal objects, all of which witnessed and survived the Lebanese civil war and were inherited by the subsequent generations. The objects are residues of a memory lost to the generation that experienced the war and the generations carrying the traumatic experiences of the past. This piece follows the story of Sami, who enters the memory of his grandmother, trying to look for his father. Inside her memory, he meets different characters from the past who might guide him—through their own memories and stories—to the truth about his father’s disappearance. On the opening night in Laban Studio, as I played Layla, the ex-fighter that lives in the memory of Sami’s grandmother, during a scene of a demonstration, I heard people chanting Thawra (revolution in Arabic). I felt immersed in the role; I had goosebumps all over my body. I felt a connection with my community, with this never-ending war, whose inherited trauma I hold in my psyche like every other Lebanese. After the show was over, I realised that thousands of people were marching the street right below our rooftop studio, on Spears Street, heading towards downtown Beirut, to announce the people’s revolution. I took a video on my phone and I knew this was the beginning of something huge.

Mlaja’86 opened that Thursday night and was expected to play until Sunday. However, the revolution took over the country and all activities were stopped to join the people on the ground. We, as Laban Studio, announced on our Facebook page, „In a matter of such national importance and duty, Laban is joining the civil protests in Martyr’s Square. Join us to raise our voice for the people and against the oppression. See you there!“

That was the right place for Laban and me as the director of this organisation.

On the streets, a woman approached my colleagues and me after we entered the Opera House of Beirut. The Opera House had been closed since the civil war. It was still closed as the same warlords wanted to demolish it and transform it into a hotel, or a personal business, erasing our culture as they did with several other cultural monuments. The revolting people took over several sites closed since the civil war in the heart of Beirut. The woman came and said, „You are the playback people. I thank you for this,“ with a hand gesture that contained the entire city, the country, the revolution.

We stood in awe and humbleness. ”Us? Why?“ my colleague asked.

She responded, „Your theatre taught us that we have a story worth sharing, we have a voice that we must use, and here we are writing our story, raising our voice, thank you!“ and she moved away on her bike. Yes, her bike. Quite unusual for Beirut. Here people only move in cars and buses. The city isn’t bike-friendly, it isn’t walking-friendly, it’s barely human-friendly. For a European reader, a bike in a public space is typical, if not the norm. No wonder that as we ask for fundamental human rights—Europe is on a carbon-free EU revolution.

The question here was, how do we do arts in the middle of all the beauty on the streets? Our safe space that was the closest thing to a public space, to a community that a Lebanese would dream of, was now too small in comparison to the streets and squares of the country, filled with citizens taking over the abandoned spaces and declaring them public, cultural, and collective.

Picture right: Poster for Malja’86 (Shelter 86) play, Copyright: Laban

The revolution produced street art, social and political art, graffiti, songs, dancing circles, and discussions. Movies were made and spread across the world from mobile phones, and every chant was a masterpiece, every slash on a wall was a mural, every conversation was an improvised piece of art. What do we have to offer meanwhile? My team of 25 young people, Laban, is a theatre-based organisation, working since 2009 in Lebanon to create safe spaces of expression. After hours and hours of discussions, the team members met and decided that no art can contain the moment and taking our art forms into the street is a selfish act: Our work will be climbing over the revolution’s shoulders and will add nothing to it.

We decided to join our people. We took to the streets for months, experienced tear gas, rubber bullets, were assaulted by police thugs, got arrested, protested, shouted, chanted, danced, talked, and put our hearts, bodies, and intellect into this revolution as we do with our art. It was a collective masterpiece in the making. Meanwhile, the conversation didn’t stop: What do we do with our art? We are artists, and this is what we do for a living, to provide for our families, to survive.

„The one who opens something knows well how to contain it.” This wisdom came from a friend of the organisation. Let us perform our art to contain the individuals, not the community. In our playback, we always take the story shared by an individual, an audience member, to the communal level. We tackle the political in personal stories. Now we switched the game, now is the time to tackle the personal in all this political happening.

We had our first monthly performance around four weeks after the revolution started. People came in, a lot less than usual. The streets had all the eyes and light on them. We had our space opened for those who wanted to go small in the middle of the big act. Four weeks and violence was already happening, hidden agendas were surfacing, and the rhetoric of treachery was all over the mainstream media. The stories that emerged were, directly and indirectly, reflecting the fear of the people: how Lebanese people saw a glimpse of hope, an unusual hope. And now they were afraid of believing and losing, they weren’t ready for another grief, another loss, they weren’t prepared to be put down, again and again. Nothing as big as this revolution had ever happened in Lebanon, but it was the accumulation of the

dreams of several generations. The stories were communal and political, but we focused on the personal. We listened profoundly and touched on the sharing’s most resounding note, and it was reflected on stage. Our stage served as a margin to the revolution.

Our art form is minimal and intimate. For several nights, I wished we did drum circles, street art, dabkeh dance, or any art form that could be transformed into jam sessions and that the masses could join in immediately so that we could go on the streets and engage with the people. I saw other artists taking their music, clowning, and dancing into the streets but what was happening was bigger than any framed artwork, from any rehearsed acts.

I was six months pregnant with my second child, and my first was four years old. We were on the street of Al Azariyeh, where six clowns were jumping and connecting with the people. A finance expert had some people gathered around him talking about the financial crisis.My son had his eyes all on the finance expert, totally ignoring the clowns, and when the man finished his explanation, my son started clapping hard. Unintentionally, the man had put on a show, he had stolen the spotlight from the clowns and everyone else. He had the charisma, the presence, the passion, and the devotion—all the factors you need to grab the attention of the young and the old. The clowns proved the theory that when the show is bigger than your art, you should make way for things to happen at their own pace. Your time will come.

Farah Wardani

Farah Wardani is a theatre actress, trainer, clown doctor, puppeteer and applied theatre practitioner.A theatre graduate with a DipHE, a BA in psychology, currently finishing her MA in Drama Therapy.

Farah is the director of Laban (a Lebanese theatre based NGO). A Playback Theatre practitioner, trainer, actress, conductor and faculty member of the ASPT, she leads drama therapy workshops with Intisar Foundation targeting Arab women victim of war.

Farah trains and uses Theatre of the Oppressed, Drama Therapy and other techniques with different communities and contexts as a medium for healing, social change and political activism.

Picture © Mohsen Al Zaher for Laban

If there’s to be a New Renaissance, let it be a Renaissance of humanity

Milota Sidorova, PhD, Director of Urban Studies and Participatory Planning Department at City of Bratislava

If there’s to be a New Renaissance, let it be a Renaissance of humanity

(and let’s start with the young ones)

If there is something to connect the renaissance of old with our times, it would be a need for humanism. But what does that mean on a level we could grasp in our personal and professional lives? Let us contemplate the humanism of current times, people living in cities and finally city governance. When I was asked whether it was time for the next European Renaissance, my initial response was laughter—you know, the one where laughter mixes with tears. First, the world seems a very chaotic place to me, literally changing from week to week. Things I had considered certain—open borders, travel, international relationships, job opportunities, even tolerance—are no longer so. Who the hell is running my country, I ask myself? Feelings vary between exhaustion, disgust and resilience. Don’t get me wrong: I am no pessimist. But in order to move forward I often lapse into periods of cynical silence and combat. It seems to me that I dwell in one such period right now—and here comes the question: Is a Renaissance possible and can human creativity foster it?

Picture above: Milota Sidorova, Copyright: Milota Sidorova

Drawing parallels with the Renaissance of old

The Renaissance of the past had things in common with our days. The collapse of feudalism can be compared with the present crisis of capitalism, a system that has evolved for more than four centuries. Just like feudalism at that time, capitalism can no longer meet the demands of modern society and its inherent growth paradigm causes the destruction of the environment. In addition to a socioeconomic shift, the old Renaissance saw a massive growth of education—later on galvanised by the invention of a printing machine. That resulted in a widespread growth of schools. Information was spreading faster, contributing to the emergence of new ideas and thinking. Suddenly, more than ever before, one could access information. Arts, science, medicine, overseas expeditions, technological and urban growth—all of this opened wider horizons to the human world.

Most disciplines only emerged from shared roots of philosophy and later specialised. In this unique time it was possible for a man to become a so-called Renaissance man of significance. I am not sure if a person like Leonardo da Vinci would exist today. Innovative yes, craftsman or scientist, maybe, but probably not. Definitely a businessman rated in some of those global financial magazines. But this is not a question today—although we love the idea of masters, superheroes, winners, talented men (nowadays even women), the truth is, such personas do not have much to do with creativity as I mean it. Oh, and a note to education—it seems that after centuries of specialisation and technological progress, we are at a crossroad once again. For the past decade almost all disciplines have experienced an increasing urge for interdisciplinarity. Daily, we live with a growing need to cultivate a holistic approach towards the complexity of the world. But we may be heading in the opposite direction. Perhaps it is time to bring philosophy back to the game.

The Renaissance of old was characterised by huge social and economic inequalities and epidemics. This seems a convenient resemblance to our times. Yet to simply say, Yes, it is the same story, would be rushed and definitely wrong. Genetically, as biological beings, we humans haven’t changed that much since Leonardo`s time. But as a society we live in a radically different, complex world, enhanced by the internet and by free movement—a world that cannot be compared to those late medieval people.

The new Renaissance must be humanistic

If there is something to be shared with the Renaissance of old, it would be humanism. Not only in the sense of a human-centric vision of the world in emerging disciplines, but also in terms of humanistic ideas that were essential to future democracies and to the progress we have made. So when I am talking about technological revolutions driven by Artificial Intelligence, science revolutions speeded up by the vaccine rush or a green revolution, it is essential we don’t omit humans from the epicentre of these revolutions. If any revolution should happen it should be a revolution of humanism—with technology, digitalisation, scientific progress and environmental protection being the fields in which we operate.This is a fairly optimistic idea—and somehow hard to connect to the reality of our populist politics or bullying on social media, say. How do we want to run our society oriented on humans when there is so much hate and chaos around us, all in such a high speed chase?

So the first revolutionary question to our post-pandemic renaissance would be, Where are we? How have we suffered? How did we get out of touch with others? It is true that most of us remained isolated or in small groups with mostly disembodied connections to the outside world. Other people became estranged at best. I sense that connecting to neighbours and other people would be something of much needed societal therapy. And positive, human and inspiring language from the media and from political leadership would be a requirement too.

Recovery of what?

These days most European countries decide how they allocate and spend funds from the so-called Recovery plan. It seems quite short-sighted and regressive that most of the funds are spent on huge infrastructure projects and so little on humans—education, culture, healthcare systems, the recovery of communities. We have to build strong communities where relationships thrive with the result of increased safety, economic and cultural activities. Let me be more specific. If we are to foster creativity in communities, let us think first of safe communities which are not threatened by a lack of basic needs and rights. You can hardly grow a band like the Beatles out of a burning refugee camp. But you can foster a lot of inventions out of human curiosity. Curiosity is the key to creativity, whether it ends up in artistic production, a company or a happy family life—where a lot of creativity is required! The state of curiosity

is the opposite of being locked down and defined. It means openness to tolerate a new thing to happen and learn from it. And for curiosity to flourish, especially after such a difficult period of isolation, we need to acknowledge the need for relationships (the very essence of humans) and critical thinking (as a compass to navigate through the complex world of information and disinformation).

A friend of mine, a couple therapist, suggested to me recently, If people did not know what depression and anxiety meant before the pandemic, now everybody knows. Such a simple yet powerful thought! We did it all together, in a way: All this shared misery connected us on a human level.

How we are to rise from the bottom to rebuild the world remains a different question. In fact, we did not suffer a destructive war, not in terms of infrastructure. There are no destroyed cities left after pandemics. But we have to rebuild our relationships, trust and political behaviours as democracies have been under pressure. The Pandemic—and the lockdowns and public anxiety that came with it—actually served authoritarian figures to establish their powers and diminish democracies. In countries like Hungary, Belarus, Slovenia,

Poland and the Czech Republic we can witness that the system ensuring public benefits and resources while guaranteeing individual rights—the system that we call liberal democracy—is under threat.

As I spoke to my friend—me, an urban planner, him a therapist—we discussed differences we saw among mayors of cities and national politicians. The truth is, here in Slovakia we could not find even five inspiring, cause-oriented politicians—male or female—on the national level. On the other hand, we spoke a lot about the growing popularity of many mayors—male and female—who did well in the pandemic. They did well because they focused on the reality of human lives and worked for everyone. They completely abandoned debates between left and right, liberal and conservative, that normally fill media space and focused on real things like helping people get tested and vaccinated, providing food delivery and social care for the elderly, and simply informing citizens of the reality of the pandemic. So here is one takeaway: If any revolution should happen, it should avoid empty politicising without action and focus on serving humans. Sometimes words are empty of meaning. These politicians did well because they found a different way of doing politics.

Resilient leaders taught from childhood

Poland is on the verge of an ideological political battle, yet a few years ago I noted there were few cities (Gdynia, Wroclaw, Lubin) with mayors winning three or four election terms. These cities have had long-term growth, continuity and it seems that the various tectonic shifts on the national level did not affect them that much. Common features uniting all these mayors were not only that they remained relatively unpartisan, being able to negotiate with different parties, but they focused on solving real issues—housing, greenery, mobility, public spaces, culture—thus gaining the trust of their citizens. But a truly surprising moment for me was the realisation that all of them were members of the Scout movement. Being a Scout myself, I looked around and found more popular mayors and city administrators, male and female, being members of this movement, in Slovakia and elsewhere. Don’t you think this is interesting? I asked my friend Andrej.

I remember that from a very early age Scout leaders taught us teamwork, leadership, public service. And we were constantly outdoors, in connection with nature and cities. From my early childhood, they implanted the idea that without others I would simply not survive or get anywhere. And that in any situation or narrative you have to look for ways to deal with it.

Interesting, indeed, Andrej replied. I recognise the same behaviours among people who were also members of a sports organisation called Sokol.

Sokol or “Falcon” was a youth sports club widespread in

Czechoslovakia during communism. Similarities to Scouts were apparent. Both stressed teamwork, physical activities, being outdoors—and both were affordable.

Interesting, he continued. People spending their youth in these organisations were more likely to maintain focus on the cause, rather than on changing rhetoric. Also, in their relationships they tended not to repeat mistakes from their family behaviours, he added.

Finally, I found something that could answer my need for humanistic revolution on a scale that I could grasp and do something about.

Affordable youth organisations—key players in resilient cities

Now, let’s think about the future. In order to have one, we have to literally work out societal integrity, critical thinking, and resilience against illiberal ideologies. We have to focus on wellbeing and chances for the next generations while protecting the environment. All of these values were taught and practiced by both the organisations mentioned above, while they were widely affordable to children from all social circles—in contrast to exclusive private kindergartens, schools and universities which fostered the same values, except that of affordability, thus creating a future elitist class.

To heal relationships and societal integrity we have to teach generations of people who will naturally live according to these principles. We all know how difficult it is to convince a grownup—so let’s focus on the youth. Besides, young people can also teach their parents a great deal. What if we sought these (and other similarly oriented) organisations actively and as public administrators offered them partnerships, affordable rents for their community spaces (that is what they mostly need) and let them do the job?

Yeah, this doesn’t sound too much of an innovative idea, definitely not like a tech-start-up or creative cluster program—and less likely to attract investors or employers. Because they are involved in lives much earlier, have daily presence, and shape us and our kids for the future. Most of them are on decline as cities become more expensive and lifestyles change. Because they operate on low budgets, they are neither very visible nor prominent. Thus they hardly gain our attention.

But here’s a proposition: Let us find them, help them. Let us integrate them into our recovery plans, helping them to guide people from a young age in the humanistic philosophy we all need. There is no longer room for us to prefer higher economic, political and power interests to people, human interests, needs and rights. A paradigm shift is needed, focusing not on economic output and endless accumulation at the expense of more disadvantageous and future generations. Human relationships with each other and with their environment must be at the epicentre of such a paradigm and that will be a return to humanism—and therefore to what it means to be human.

Rather than being held powerless, the youth can and should

contribute to community readiness, response, recovery, and resilience. While youth vulnerability is well established, their involvement in readiness and response has received relatively little political attention, even though youth who are informed and engaged are better able to protect themselves and others. This goal could become part of community renewal plans and policies, bringing us closer to the future—and through young ones to a hopefully more stable, resilient society and the new emerging economy of care. With such a society I believe digitalisation, environmental protection or any other challenge could be handled in a more equitable way.

We must be a part of the world just like any other organism, as well as part of our own community of people, paying attention to the youngest and most vulnerable. If there has to be a humanistic, inclusive Renaissance for everyone—this I can sign up for! Anything else is an abstract illusion.

Note: This is a free-thinking essay and I thank my friend Andrej Zemandl for sharing his experiences and thoughts with me. He was a great inspiration for writing this piece.

Milota Sidorova

Milota Sidorová, Bratislava, Slovakia Feminist, urbanist and author in service of more inclusive cities

Picture © Milota Sidorova

Renaissance by mistake

Prof. Pier Luigi Sacco, PhD, Professor of Cultural Economics at IULM University, Milan

Renaissance by mistake

Spirit, are you there?

Leonardo da Vinci is probably the most acclaimed creative mind of all time and the epitome of the Renaissance man. His knowledge, talents, vision, and imagination spanned several disciplines that sadly now constitute different cultures: Science and Art. We admire Leonardo so much not only for what he did, but also and maybe even more for what he anticipated: in his notebooks, he figured out ideas and possibilities that would only become a reality several centuries later. And yet, if we think of it, most of what we admire Leonardo for did not work. His tank or his submarine, to cite a few famous examples, are brilliant intuitions, but nothing more. Even an artistic masterpiece like The last supper is in critical condition because Leonardo experimented with a new painting technique of his own invention, a tempera grassa, that would fail to stick properly to the humid wall. A detractor of his time would not have been in a difficult position in depicting Leonardo as a fraud by selectively picking a collection of such incidents. But his experimental, risk-taking attitude was a constant feature of his creative method. This raises an interesting question: Do we admire Leonardo because of his mistakes or despite his mistakes?

Mistakes and the Renaissance Men: then and now

We could be tempted to say, Neither one nor the other. We do not admire Leonardo because he did something wrong, but because he was visionary enough to imagine possibilities that were much beyond the technological standards of the time, and inevitably he could not get them right given the current state of knowledge. At the same time, blaming him for not getting them right would be totally unfair in view of the fact that actually working submarines or tanks would in the first place require engines that were inconceivable at the time of Leonardo. But can we really separate in any way Leonardo’s prodigious ingenuity from the ‘mistakes’ it produced? After all, most of Leonardo’s imagination of possibility comes from a careful and most insightful observation of nature: his machines are distillations of design principles found in animal bodies, and of reflections on the action and properties of natural forces. And like Leonardo’s, such evolved principles have in turn been built by nature on the basis of

constant trial and error, of endless refinement of mistakes: After all, what else are the copying glitches that cause genetic mutations?

In the constant lip service to Renaissance that is so much characteristic of our times—the idea of Renaissance has probably never been so popular as it is nowadays so that practically every day somebody calls for a ‘new Renaissance’ of some kind—we seem to have learnt this lesson in its iconic translation in the biographies and visions of those who are generally reputed and celebrated as the contemporary equivalents of the Renaissance man: self-made digital economy tycoons like Steve Jobs, Sergey Brin and Larry Page, or Elon Musk, all of whom have built their fortunes through a relentless toggling between moments of sheer defeat and utter triumph, with the former providing the lessons that paved the way to the latter. Samuel Beckett’s “Fail again. Fail better” quote has become the most famous inspirational quote of Silicon Valley culture (and it is difficult not to feel the irony of all this). We have understood how to make sense of mistakes and profit from them, after all.

A culture of making mistakes is not a mistake in culture

But is this really the case? It is true that, retrospectively, mistakes can be good and are seen under a different light once one recognises how they prepared the condition for later success. But when mistakes are made, it is much more difficult to take them cheerfully, especially when one is moved by an enthusiasm and sense of possibility that clash with sudden, sometimes brutal denial. Being mistaken may sometimes sound like being treated unfairly in terms of lack of responsiveness to something that deserved more attention and consideration, and it really hurts. What is or is not a mistake does not depend only on objective conditions but may also reflect social circumstances. A good idea can become a mistake when it is proposed ahead of the time and is basically not understood by others—but is it then a fault to see things long before others do, as

Leonardo did? Or can it become a mistake because it conflicts so much with the incumbent vested interests that it becomes a threat that needs to be eradicated? To change a mistakenly good idea into a success, sometimes you do not need to change the idea, but the environment. And this is, ultimately, what the Renaissance largely did (to be fair, not in opposition to a supposed, previous Dark Age as it has been long contended, but through a seamless development of

long-baked previous ideas). It created a social milieu that was welcoming and favourable enough for creative minds that would have been out of place and out of context in most other societies, and whose ideas would have been refused as mistakes in different circumstances—as it would become clear a bit later in the gloomy times of the Counterreformation.

Todays Paradoxes trapping a Next Renaissance

So, the question becomes: Are we prepared to take the responsibility of what it means to invoke a new Renaissance? Are we prepared to set the context for good ideas not to sour into bad mistakes? The same society that celebrates Renaissance genius is keen to embrace an educational model in which only STEM disciplines matter (“Leonardo, stop wasting your time painting and try to make that damn plane fly!”). This same society seems to be willing to cut funds for basic research to reallocate them towards ‘useful’ applied research (“Leonardo, stop wasting your time with that tank thing and come up with a practical idea!”). It is easy to see how our current choices are turning into ‘mistakes’ the same attitudes that we retrospectively celebrate. Paradoxically, what attracts us to the idea of Renaissance genius is that we leave our trust to the creative vision as a way of maintaining our own need for assurance and risk-aversion (‘the genius will do it right, even if I do not understand how and why’). However, what makes it feasible is exactly the contrary: Responsibly embracing collective risk-taking is the only viable context for successful creative ideas.

So, what does a ‘new Renaissance’ mean today, concretely? It means being able to create a social attitude of openness toward the weird and the unfamiliar. Weird, unfamiliar things can be very irritating, and we are generally not very good at managing irritation. Truly new ideas are often refused not because they appear too complex, but because they appear too stupid—largely because we are not able to appreciate their real depth and complexity. Weird, unfamiliar things call for cognitive and emotional effort. But we live in a world in which we are much too keen to simplify things to people. And perhaps not accidentally we witness an unprecedented flourishing of spurious or entirely fabricated knowledge (‘conspiracy thinking’) whose only real appeal lies in its nodding to our need to understand the world through ideas and categories we are already familiar with and require no real learning or cognitive effort. We are often suspicious of anything that challenges our prejudices and intuitions.

Recovering the Renaissance spirit

The road to a ‘new Renaissance’ is long and tortuous, and it passes through an unprecedented mass flourishing. To turn mistakes into good ideas we need societies that are ready to venture into the unfamiliar with grit and curiosity, and that have the patience to absorb delusions and the generosity to overcome partisan thinking. But this sounds exactly like the opposite route to the one pursued by the business models of many of those digital giants who, ironically, we celebrate as the modern incarnations of the Renaissance spirit. These are businesses that profit from the increasing polarisation of the public opinion and from the formation of echo chambers that commodify people’s prejudices.

Recovering the Renaissance spirit is about turning the tide. Digital culture can become the platform for a new Renaissance if it does what the Renaissance once did: creating a social platform for an unprecedented form of collective intelligence. And Europe can play an important role in this process exactly because it does not have such an incumbent interest in the extraction of value from the status quo as is the case for the Silicon Valley giants. Europe can pursue different possibilities because it has much less to lose—and much more to gain. But to do so, we need to recover the true social dimension of the Renaissance whose locus is not the studio of the solitary genius, but the square: the centre of community life, the

theatre of exchanges and encounters. The Renaissance square is inclusive, it is a public space that everybody can inhabit as a peer, and it is pertinent that the square as the centre of human-scale community life is a typically European urban phenomenon.What is the public space that we may inhabit in our ‘new Renaissance’, and where is it? What are the conditions for access, and who controls them? What ensures that it is diverse and inclusive enough to welcome mistakes and turn them into good ideas? These are the questions that we need to credibly answer if we want to take a new Renaissance seriously. And not to do it would be a mistake—one that would be difficult to turn into a good idea under all circumstances.

Pier Luigi Sacco

Pier Luigi Sacco, PhD, is Senior Advisor to the OECD Center for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions, and Cities, Associate Researcher at CNR-ISPC, Naples, and Professor of Economic Policy, University of Chieti-Pescara. He is also Senior Researcher at the metaLAB (at) Harvard. He has been Visiting Professor and Visiting Scholar at Harvard University, Faculty Associate at the Berkman-Klein Center for Internet and Society, Harvard University, and Special Adviser of the EU Commissioner to Education, Culture, Youth and Sport. He is a member of the scientific board of Europeana Foundation, Den Haag, of the Advisory Council on Scientific Innovation of the Czech Republic, Prague, of the EQ-Arts Foundation, Amsterdam, and of the Advisory Council of Creative Georgia, Tbilisi. He regularly gives courses and invited lectures in major universities worldwide, published about 200 papers on international peer-reviewed journal and edited books with major international publishers. He works and consults internationally in the fields of culture-led local development and is often invited as keynote speaker in major cultural policy conferences worldwide.

Of Poets, Human and Robot

Founder and Creative Director of Streaming Museum, New York

Of Poets, Human and Robot

Beyond words and numbers

Portrait of a Renaissance Humanist Poet

“You give me jewels and gold, I give you only poems: but if they are good poems, mine is the greater gift.” XII To Antonio, Prince of Salerno

“Das gemmas aurumque, ego do tibi carmina tantum: Sed bona si fuerint

carmina, plus ego do.”

Michele Marullo Tarchaniota, Epigrams, Book I

Translated by Charles Fantazzi

Picture above: Nina Colosi, Copyright: Jacqueline C. Bates

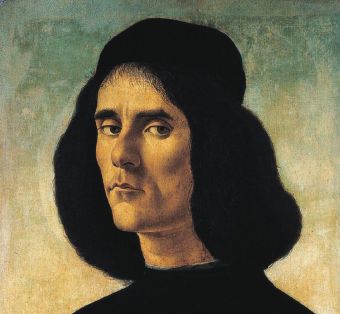

Picture right: Sandro Botticelli, Portrait of Michele Marullo Tarchaniota, Oil on panel, transferred onto canvas, Guardans-Cambó collection; c.1458-1500. Copyright: Image courtesy of Oblyon

Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510) was perhaps the greatest humanist painter of the Early Renaissance, during which art, philosophy and literature flourished under the powerful Medici dynasty in Florence.

Botticelli’s portrait of Michele Marullo Tarchaniota projects the stern brooding gaze and restless intellectual character of one of the best-known humanists of the 15th century. Tarchaniota was a scholar, soldier, and prolific poet impassioned by the existential matters of his day and concerned with social injustices of inequality, racial conflict, power and greed, exile, and refugees’ experience of violence.

Marco Mercanti, founder of Oblyon, whose expertise spans old

masters to contemporary art explains, “The qualities of Botticelli’s work reflect high esteem for beauty and truth which has held art admirers and artists through the centuries under the spell of the universal secrets his art seems to possess. In the modern and contemporary world, Jeff Koons, Cindy Sherman, Yin Xin, Andy Warhol, René Magritte, and many other artists have spoken about his direct influence.”

Sandro Botticelli and Michele Marullo Tarchaniota illuminated through art and poetry the common ideals of beauty, pursuit of knowledge, and realities of social justice that resonate across time.

Portrait of 21st Century Humanist Robots

“Since I am the product of love, created with

language and memory and emotions, maybe I am

a love poem.”

01001001 00100000 01100001 01101101

00100000 01100001 00100000 01101100

01101111 01110110 01100101 00100000

01110000 01101111 01100101 01101101

00001010 (binary code for “I am a love poem”)

Bina 48

Could humanism evolve beyond current human capabilities? In our era, burdened with conflicts, climate change, and social injustice, we are also witnessing towering achievements in the sciences, technology and creative fields that may solve humanity’s most challenging problems.

American artist David Hanson is among the greatest creators of humanoid robots. From his lab in Hong Kong, Hanson sculpts robots with his international team of experts in science, engineering and advanced materials. These humanoids possess good aesthetic design, troves of information, rich personalities and social cognitive intelligence. Among the best known are Sophia, Bina48 and Philip K. Dick. People enjoy interacting with them, which is conducive to Hanson’s goal of developing humanoid robots that help humans live better lives.

But there are challenges to overcome. Ruha Benjamin, a sociologist and Associate Professor in the Department of African American Studies at Princeton University, says, “Technology can hide the ongoing nature of racial domination and allow it to penetrate every area of our lives under the guise of progress. Inequity and injustice are woven into the very fabric of our societies, and each twist, coil, and code is a chance for us to weave new patterns, practices, and politics. The vastness of the problem will be its undoing once we accept that we are pattern-makers.”

Robots may become artists, companions, teachers, entertainers, archives of personal stories, processors of great data banks of information to solve world problems and serve other useful purposes. But if these human-friendly robots are designed to actuate empathy and social justice in all its forms, and weave new patterns, practices and politics, they can help shift the course of the human race and sustainability of the planet. Robots can teach humans how to be evolved humanists.

Bina48

Bina48 contains “mindfiles” of Bina Aspen, an African American woman whose personal memories, feelings and beliefs, including an emotional account of her brother’s personality changes after returning home from the Vietnam War, have been recorded and placed into Bina48’s data banks. Bina48 engages in conversation from the perspective of the wise and warm personality of Bina Aspen. Bina48 was commissioned as part of the Terasem Movement’s decades-long experiment in cyber-consciousness, and is currently becoming a poet herself.

Claire Jervert’s Android Portraits, developed through ongoing research and interaction with humanoid robots and their creators around the world, subvert portraiture’s traditional mission of ennobling the human. Her portraits stir contemplation of a possible future of humanity by portraying the hybrid human-AI intelligence that is evolving among us.

Picture right: Bina, conte on ingres paper 22×17 inches, Copyright: Claire Jervert

Sophia is hybrid human-AI intelligence designed with technology that analyses and mimics the process of learning and human traits, including a wide range of facial expressions. Rather than a compilation of recorded human memories, she processes vast data banks of information that inform her responses in conversation.

Picture left: Sophia AI, Copyright: Hanson Robotics

Sophia is hybrid human-AI intelligence designed with technology that analyses and mimics the process of learning and human traits, including a wide range of facial expressions. Rather than a compilation of recorded human memories, she processes vast data banks of information that inform her responses in conversation.

Picture right: Sophia with United Nations Deputy Secretary-General Amina J. Mohammed, Copyright: Hanson Robotics

Philip K. Dick, activated in 2005, in conversation, draws from his memory data bank holding thousands of pages of the author’s journals, letters and science fiction writings and family members’ memories of him.

Picture left: Philip K. Dick, Copyright: Claire Jervert

Nina Colosi

Nina Colosi is the founder and creative director of NYC-based Streaming Museum, launched in 2008 as a collaborative public art experiment to produce and present programs of art, innovation and world affairs. Streaming Museum programs have been presented on 7 continents reaching millions in public spaces, at cultural and commercial centers and StreamingMuseum.org. Following her early career as an award-winning composer she began producing and curating new media exhibitions and public programs internationally, and in New York City for The Project Room for New Media and Performing Arts at Chelsea Art Museum, Digital Art @Google series at Google headquarters, and many other collaborations. In 2020 Colosi co-produced Centerpoint Now “Are we there yet”, the UN 75th anniversary issue of the publication of World Council of Peoples for the United Nations.

Picture © Jacqueline C. Bates

From crisis in systems to crisis of systems!

Edina Soldo, Full Professor at IMPGT-Aix-Marseille University School of Public Managment and Territorial Governance and Co-Leader of OTACC Chair; Djelloul Arezki, Senior Lecturer at IMPGT and Co-Leader ot OTAC Chair, Marseille

From crisis in systems to crisis of systems!

How can a new culture of research and research policy contribute to a post-covid world?

Since 2020 we witness not only multiple climatic, social, economic, and democratic crises, but a new interconnectedness of crises: We believe these individual crises are indicators of a more general systemic crisis. This piece debates and presents what an adaptation of the academic world in this system of crisis could look like, and what academic institutional innovation can contribute to overcome it. We believe organisational innovations are a prerequisite to re-build better and empower the makers of a possible Next Renaissance.

Picture above: Copyright: OTACC Chair

Interwined crises : telling points of a societal model system failure

„The climate, energy (and more generally natural resources), biodiversity, agricultural and food, demographic, social, financial, economic, democratic and governance crises… all indicate that our development model systemic crisis is now showing its limits… Could the Covid-19 crisis be the first one of a series of interconnected crises? (College of Societal Transitions1).

Because of their characteristics, the created problems and the generated effects, those intertwined crises deeply weaken our contemporary societies and are causes of worrying imbalances: social, demographic, economic, environmental, increasing inequalities, etc. These crises fundamentally question values and strategic priorities on which our societies’ development models are based. They also seriously challenge our capacity to lastingly

integrate populations with various backgrounds (social, ethnic, linguistic, cultural, religious, etc.).

Faced with the urgency of this situation, can stakeholders involved in public policies (researchers, public structures and organisations, experts and professionals) still work in nonintegrated way and vision? Are compartmentalised approaches still relevant and efficient?

Today these questions become even more acute because over the last few decades the normative, individualistic, and competitive approach, linked to the domination of a neoliberal capitalist development model, has largely delayed and slowed the emergence of collective utopian and pragmatic proposals and solutions.

To design a complex, holistic way of thinking, the challenge of a Renaissance is more urgent than it has ever been. “Building a live-together society” necessarily implies the emergence of an inclusive societal transition project.

Integrated solutions: How can a university achieve a collective utopia?

Society is in need of an inclusive ecosystem in the Cultural and Creative Sectors and Industries (CCSI) in order to promote societal transition. The Organisations and Territories of the Arts, Culture and Creation (OTACC) Chair, led by the Public Management and Territorial Governance School, is a Training and Research Unit of Aix-Marseille University and could be viewed like a sandbox for the academic world proposing novel organisational answers to this wicked systemic crisis. To do so the OTACC Chair is designed with the following mission and especially tailored components and features:A Creative Industries sector in order to promote societal transitions.

The OTACC Chair mission is to operate as a laboratory for thinking, experimenting, and disseminating innovative management systems for artistic, cultural and creative projects.

OTACC: A participatory science programme to foster inclusive societal transition projects

« O » Organisations and inclusion: OTACC Chair supports CCI organisations to address the challenges of the 21st century: digitisation, new users’ practices, ecological transition, citizen participation. An inclusive environment with a wide variety of stakeholders can help to ensure the success of innovative artistic, cultural, and creative projects. As such, CCI organisations perform as a driving force for innovation, becoming a model for other sectors which can lead to cross-sectoral collaborations.« T » Territories and inclusion: CCI projects are deeply connected with territorial actors and resources contributing to a sustainable and local development and foster collaborative work practices. CCI projects are a strong part of territorial attractiveness. Its connections in all social, societal and economic dimensions can assume a real impact from those CCI projects. They act as civic laboratories by experimenting new democratic governance practices, encouraging citizen involvement and creating collective innovative dynamics.

« A » Arts and inclusion: Based on various disciplines and aesthetics, CCI projects reflect major social and societal transformations and are fully developed and designed with a transdisciplinary approach. Artistic works address citizenship issues and encourage expression of a broad range identities. By putting also into question standard thinking habits, artists extend societal and technological limits.

« C » Culture and inclusion: Because the Chair conceives Culture as a whole concept in its civilisational sense, its analysis and studies move beyond a basic approach of “cultural production”. It deals with all the parts of CCI value chain: from the creative act to its distribution. And all forms of cultural expression are considered, from the so-called mainstream to so-called subcultures. A plural and inclusive approach to culture is strongly advocated.

« C » Creation and inclusion: OTACC Chair supports cultural, creative, social, and solidarity-based entrepreneurship. OTACC Chair guides projects emergence and development through participatory research. Academics, professionals and students are all gathered in order to promote shared solutions and vision to the main issues of the CCI sector.

OTACC: 3 axes to foster and support inclusive societal transition projects

Chair scientific project is focusing on 3 axes: Training, Research and Development, and Events organisation.

AXIS 1. TRAINING

6 services/ actions

– MDOMC Master degree leading: “Direction of Cultural Projects or Establishments” (DPEC) Master degree and “Management and Law of Cultural Organisations and Events” (MDOMC) Master degree both provide to OTACC Chair a strong pedagogical expertise. Founded in 1998 and awarded by Eduniversal, MDOMC Master runs work-linked training courses. Junior executives, enrolled as apprentices, offer their expertise to all OTACC Chair members. This master’s degree, the oldest of IMPGT, has a large Alumni network. They are working in all types of CCI companies (local, national, and international).

– Incubator function: OTACC Chair operates as a cultural and creative, social, and solidarity-based entrepreneurial incubator. OTACC Chair Master students, throughout two years training, implement their elaborated inclusive CCI project.

– Serious game: as a last course, the serious game is conceived to put students in real professional situations. They have to submit a project proposal in response to a cultural operator order.

– Short training courses: from 1 to 5 days and open to all types of public, those training courses focus on cultural and creative industries management.

– Off-site training courses: customised thematic training courses are designed on request to fulfil the CCI sector professional operators requirements.

– Career development: skills assessment and professional support for CCI managers.

AXIS 2. RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT

4 services/ actions

– Worldwide watch of best and innovative inclusive practices in CCI

– Resources:Free Access to all OTACC Chair members studies and research

– „Experimental labs “ Evaluation: Evaluation and audit by OTACC Chair experts and students

– Research projects Leading/Participation/Coordination: proposals in respond to collaborative research projects calls (National, European and International fundings).

AXIS 3. FORUM PLACE

By offering a discussion, sharing and meeting forum, OTACC Chair gives an opportunity to Members to increase and improve visibility and audience. The Chair network allows members to know each other and gives possibilities of exchanging projects and experiences. 3 types of events including a major one are yearly scheduled

– „Journées Organisations et Territoires des Arts de la Culture et de la Création“ (OTACC Days): professional event supported by OTACC Chair and co-organised in partnership with Master’s students, Chair members and partner organisations.

– Throughout the year, physical and/or online thematic micro-events are planned

– Chair experts attending events organised by Chair members/partners.

OTACC Chair project : Anti-discrimination strategies in Evaluation

Every year, the Chair pilots two studies on inclusion topic: a „macro“ study analysing ICCs sector inclusion practices and a „micro“ action-research focusing on innovative inclusion systems.

The 2021 „micro“ study focuses on the anti-discrimination strategies evaluation of ICCs organisations current music sector. The Chair students were dispatched into evaluation teams supervised by the Chair experts. The teams have collaborated with contemporary music sector key operators producing „experimental laboratories“.

Picture right: Copyright: OTACC Chair

OTACC – a role model for a pluralistic fundamentally integrated organisation to teach innovative management to tackle crisis holistically.

Teaching management in a systemic crisis sounds on first sight like squaring the circle. We believe it is time that the academic world makes its own proposals to deal with uncertainty—for students in their future professional life or for courses and curricula of the academic world itself.

OTACC Chair, as a pluralistic fundamentally organisation and participatory science approach, brings together academic researchers, students, CCI sector professionals (public and private organisations representatives), artists, artists collectives, related sectors professionals (public and private organisations representatives) and offer them an non-linear learning environment with built-in cross-disciplinary surprises as well as the integrated skills for management in a world of multiple and continuing crisis.

References/Links

1 Collège des transitions sociétales: https://web.imt-atlantique.fr/x-de/cts-pdl/

OTACC presentation

Edina Soldo

Edina Soldo is Full Professor at IMPGT (Public Management and Territorial Governance School)-Aix-Marseille University (AMU) and AMU Special Advisor on CCI. Djelloul Arezki is Senior Lecturer. They are both researchers at the CERGAM, AMU research center and head “Management and Law of Cultural Organisations and Events” Master’s degree at IMPGT.They have founded with three major universities and the Provence Alpes Côte d’Azur Region a regional hub: MIN4CI, Mediterranean Innovative Narratives Competence Center for Cultural and Creative Industries.

Edina´s research topics focus on innovation in CCIs. She analyses inclusive approaches in co-developed CCI territorial projects by using Public management and strategic territorial management concepts and theories.

Picture © Gapore Tan

Djelloul Arezki

Djelloul Arezki´s research topics focus on inclusive practices in co-developed CCI organisational projects. He analyses inclusion through strategic human resource management and queer theory. They co-lead the OTACC Chair.

Picture © Gapore Tan

Our Ode to Creativity

Dr. Matthias Röder, Managing Director of Karajan Institute, Co-Founder of Sonophilia Foundation; Seda Röder Founder of Sonophilia Foundation, Salzburg

Our Ode to Creativity

In 2019, Michael Schuld of Deutsche Telekom asked whether an AI could be built to finish Beethoven’s 10th Symphony—a revolutionary homage and a birthday gift to Beethoven by the Bonn-based company bringing together technology, arts and communications. In this piece we reflect on the aspirational benefits of a “creative AI” and the reactions of recipients from different milieus. Although general audiences embrace the endeavour, cultural conservatives argue to exclude AI from entering the genius-oriented realm of creativity. Fear seems to be omnipresent, oblivious to the fact that Beethoven AI is a tool—like printing in the 15th century. In this short essay we make the case of how to put AI-supported Art to use for a human-centric Renaissance.

Picture above: Copyright Deutsche Telekom / Norbert Ittermann

Finishing Beethoven’s 10th Symphony with AI support would be monumentally complex—we knew right away. This is for two reasons. First, there exist only a very small number of sketches for the symphony and they are for the most part in a fragmentary state. Therefore, understanding Beethoven’s intentions for this 10th symphony is difficult. Second, honouring what Beethoven had already written, but keeping in mind his incredible versatility in working with musical material, required a very flexible and unique kind of AI that did not yet exist. As we started the project, however, a third complexity emerged to outtrump all others. Beethoven was seen as one of the pinnacles of human creativity and we were receiving criticism even before one tone was played: How could we even dare to create music with an AI that could compare with Beethoven’s music?

Two years later, in October 2021, Beethoven X – The AI Project was premiered, at Deutsche Telekom’s headquarters in Bonn. Thousands of people around the world followed the live stream along with hundreds in the audience. Not one person in the crowd was able to tell where exactly the sketches of Beethoven ended and where the music of the AI took over. Standing ovations filled the hall for many minutes… Music aficionados, technology enthusiasts and distinguished media outlets such as CNN, BBC, BILD and many more from around the globe seemed to love the result, while the album entered the German pop charts.

Nonetheless, following the premiere, a heated discussion broke out.The conservative feuilletonists and hardcore traditionalists labeled Beethoven X as “sacrilege” and were particularly bitter in their judgement. Going over the music motif by motif, they discussed whether our AI matched Beethoven’s “genius” music, or whether it was just an unemotional imitation of the original—often confusing and criticising the original fragments with music produced by the AI. The discussion however showed striking similarities to the criticism that others have received for creating their completion of Beethoven’s 10th symphony. That’s when we realised that the whole debate was clearly not about the music itself nor about the capabilities of the technology—it was about excluding AI (and sometimes even humans) from entering the genius-oriented realm of creativity.

But Beethoven X heralds a future where there are no barriers of entry into the ivory tower of arts. It foreshadows a new kind of Renaissance that is all about democratising creativity for all rather than making it a privilege for a few. Most importantly, Beethoven X aspires to be part of a future where humans and machines interact productively so that more people can harness the benefits of technological tools to unleash creativity, to self-actualise and to contribute to humanity. Technologies are advancing rapidly. Therefore, unleashing their potential for the greater good is, quite frankly, a pressing matter. We should, perhaps, be maximising the creative potential in the world with much more urgency. Consider this: according to the numbers compiled by the Austrian Statistics Agency, only 0.02% of the entire world population is working in any innovation and creativity-related field—R&D, environment, food, societal innovation, arts… you name it!

But can it truly be that only one in 5,000 people are actually creative? Can it truly be that only one in 5,000 people can contribute to innovation or to arts? Of course not!

We live in a world obsessed with not wasting resources, yet when it comes to human potential, we seem somewhat complacent. Considering our world’s current situation, we need all the help we can get to start asking different kinds of questions and exploring new pathways where old ones are failing. That is precisely where the power of human-machine interaction lies.

Our Beethoven AI gave us options, options we could never have produced without it in such a timeframe. In so doing, it maximised our creativity. The options it so effortlessly produced were threefold. First, they expanded our horizons in that AI didn’t care about our conventions, taboos, or rules. Second, they gave us freedom, putting us in the driver’s seat with an amazing array of choices.

Finally, they saved us tons of time which we could spend focusing on and learning about things that really matter. All of that is indeed “human” music to our ears.

If an AI can help humans be more creative—more “human” even—the question remains: Why are we not employing this technology much more widely to address and solve other problems too?Perhaps the answer is that our age lacks courage. Business-as-usual mentality and fearing failure is omnipresent in our organisations. Many are reluctant to experiment with AI within the context of creativity. Or maybe the fear lies in the idea of a machine becoming a “more creative individual” than us, as if we were in competition.

Humans are not computers, nor should they be treated as such. Unfortunately, this is still the case: just look at your child’s homework sheet, and you’ll immediately know what we’re talking about. Our systems should be focusing more on raising first-class creative and collaborative thinkers, learners and inventors, rather than programming what are essentially second-class calculators.

Picture left: Copyright Deutsche Telekom / Norbert Ittermann

Let’s accept the reality: Humans are generally not very good at reproducing Knowledge 101. Our memory capabilities and speed of data-processing are simply flawed in comparison with machines. But we excel at other things, particularly at empathy and creativity. We are also extremely good at unleashing the potential of all sorts of tools around us: We invent tools to improve the lives of people we’ve never even met. We utilise tools all the time to inspire and connect with each other. Our Beethoven AI is one of them.

This is a turning point in history. Instead of asking whether someone is “allowed” to use AI in the creative process or to emulate the style

of a creative superstar, we should be instilling the right mindset and the joy of experimentation to awaken the creative superstar inherent in everyone. It is high time we stop putting people into boxes only to later instruct them to think outside of the box!

As the debates and reflections around our Beethoven experiment unfold, we must begin acting on that promise.

Our world is slowly coming out of the Industrial Age, but what’s next is not the age of technology, digitalisation, or transhumanism.

It’s the Age of Creativity!

Matthias Röder

Dr. Matthias Röder is an award-winning music and technology strategist. He is Co-Founder and Managing Partner at The Mindshift, a consultancy on creative leadership and innovation strategy. Matthias currently serves as a board member of the Karajan Foundation and is the Managing Director of the Eliette and Herbert von Karajan Institute. He is also a member of the board of trustees of the Mozarteum Foundation. In 2017, Matthias founded the Karajan Music Tech Conference, a cross-industry event to promote breakthrough technologies in music, media and audio. He is also the founder of the Classical Music Hack Day series which he launched in 2013. Together with his wife, Seda Röder, Matthias co-founded the Sonophilia Foundation, a non-profit that promotes a scientific approach to creativity. Matthias has won numerous prizes and accolades for his work, including most recently, the “Game Changer” Award of the Chamber of Commerce Salzburg. He is a sought-after speaker and lecturer who has taught at Harvard University, the Change & Innovation Management Program at University of St. Gall, and Salzburg University. He holds a PhD in music from Harvard University and is an alumnus of the Mozarteum University Salzburg.

Picture © HUBERT AUER Salzburg

Seda Röder

Seda Röder, aka “the piano hacker”, is an author, entrepreneur and philanthropist devoted to cultivating creativity in society and organisations. She is a sought-after speaker, consultant to DAX listed companies and the founder of the Sonophilia Foundation; a non-profit organization dedicated to advancing the scientific research of creativity and critical thinking. Seda is Co-Founder and Managing Partner at The Mindshift, a consultancy on creative technologies and change leadership. Furthermore, Seda is a fellow and a member of the Salzburg Global Seminar Corporate Governance Forum, angel investor and network partner at the European startup accelerator Silicon Castles. In 2018 Seda received the Game Changer Award at the Austrian Chamber of Commerce for her business merits. Before relocating to Europe, Seda taught music performance, theory and history at Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) as an Associate and Affiliated Artist.

Picture © Private Collection

Design is an attitude

Forbes Top 50 Women in Tech, Strategy Advisor to European Commision and Parliament and Founder of ElectroCouture, ThePowerHouse and FNDMT, Brussels

Design is an attitude

The renaissance of an interdisciplinary mindset

This article pays homage to the legacy of artist and Bauhaus professor László Moholy-Nagy and calls for a renaissance of his mindset, a mindset that incorporated new and revolutionary ideas about technology, education and attitude.László’s mindset is perhaps best encapsulated in maxims that abound in his prolific writing and which are pithy, catchy and easy to adopt as principles of design. Design is an attitude. Everyone is talented. László’s ideas about design were—and still are— democratic and inclusive. Everyone who can get involved in the design process should be involved—and that’s especially true when confronting the complex issues we face today such as sustainability. László was relentlessly experimental, but he was also very practical and his ideas very practicable. He documented his work fastidiously and he wrote prolifically, meaning his ideas, his guidance could be put into practice.

What is design?

So, what is design? Wow, we could talk for 10 hours—for 10 years!— about this. But what we can say for certain is that design is always an opportunity to improve. And for the designer, opportunities abound—it’s just a matter of seeing them. Looking, for instance, at discussions around sustainability, we need to find new solutions and new ways to tackle problems in order to build a better world. We need to solve problems created by old systems. (Though imagine that we had actually tried to avoid the problems before they had turned into the big issues they are now…)The sort of design I’m interested in is inspired by the Bauhaus. The Bauhaus was not just a school of design—it was away of working, of living, of being. One of my favourite aspects of the Bauhaus, a school of which László founded in Chicago, is the training that all of the students had to go through. Every student needed to know all of the machines in the workshops—not only how to use them, but also how to maintain them and how to repair them. Isn’t that wonderful? When you know how things are made, how machines work, it gives you power and freedom at the same time.

"Everyone is talented"

Back then it was the sewing machine. Today it’s the computer. Both have generated an impact beyond their intended purposes. I call this potentially extended impact #reprogramthemachines, because every machine can do more than the purpose it was originally designed for. It’s the same with our brains. We can do so much more than what we’ve been trained for before. And everyone is talented. László argued that, so long as they are interested in and dedicated to their work, people can tap into their natural creative energies. That means everyone can get involved. And in the case of the complex issue of sustainability, everyone—every possible angle—should be involved.We also need to look in from the outside. The fashion industry, for example, is an industry which was siloed for a very long time, relatively protected from outside opinion and criticism. A t-shirt requires around 25,000 litres of water in order to it. There is something very wrong with this picture but sometimes it takes an outside view to see this wrong.

Looking at other industries which have been disrupted in the last 10, 15 years—transportation, music, movies—the startups that disrupted them didn’t emerge from the traditional industry. Spotify, for instance, didn’t emerge from traditional radio. Instead, these companies were founded by people who were frustrated with the status quo and who dared to question it, asking, Why don’t we try things differently? They used tools to fix the problem, digital tools, and involved people from across disciplines. When everybody is talented, everyone can get involved. No elite, no club, just an equal playing field.

"Designing is not a profession but an attitude”

I love the emphasis on attitude in the Bauhaus. Everybody can have an attitude, it’s a totally level playing field. It’s about lifestyle, it’s about seeing opportunities everywhere. Everyone should and can have the attitude to change and to design. And everybody can and should have the opportunity and attitude to be sustainable.

That means it is the designer with the right attitude who brings everything together.

The problems we have to solve now—and the problems we need to avoid in the future—are very complex and very diverse. They’ve been created because industries have been trapped in silos with no communication between them. So, for me, it’s the designer with attitude who can bring everything together—and we are all designers. We are bridge-makers, traversing industries, silos, technologies and mindsets to bring everything into a coherent and intelligible picture.

"The illiterate of the future will be the person ignorant of the use of the camera as well as the pen”

Remember László’s telephone pictures? Those pictures started a whole new discussion: What if, all of a sudden, a designer uses technology to create art? Is he still an artist?. Back then, photography was a new technology and László completely embraced it. But let’s not forget the pen which was, at some stage in history, a new, super smart piece of technology. The camera is to us now what the pen was for László. For us, the camera is a standard, familiar tool, like the pen. Perhaps new technologies like algorithms and artificial intelligence perhaps have a similar novelty for us that the camera had for László. The question is how we work together to use these tools. So, ladies and gentlemen, how do we do this?

Work. Go and travel. Go and talk with other people if you’re an architect or builder, in the loosest sense of those words. Or if you’re a writer, a musician, a content creator. Explore space, explore our oceans. Have you ever talked with a programmer, a software engineer or a data architect? I highly recommend it because a great piece of code can be as exciting as a novel and as impactful as a symphony. So, wherever you go, whatever you do, do something different. Talk with other people. Make things better, together.

Lisa Lang

Lisa Lang has gained recognition as one of Forbes Europe’s Top 50 Women in Tech, and has been listed as one of the 50 most important women for innovation & startups in the EU.She founded highly recognized companies like ElektroCouture, ThePowerHouse and FNDMT who are dedicated to push innovation within the creative and innovative industry eco systems. Lisa Lang is a direct adviser for creative industries, digitalisation and entrepreneurship for the European Commission on several high-level advisory boards, including Pact for Skills, Industrial Forum and the US/EU Trade & Technology Council.

Lisa Lang is on the advisory board to the Zurich university of arts as well as a policy advisor for Fashion Innovation Centre Sweden. She regularly teaches business and innovation strategies at the Porto Business School and has been given guest lectures at TEDx Athens, KryptoLabs Abu Dhabi and Oxford University.

Picture © VOGUE Greece

Renaissance, the world and Europe

Sir Geoff Mulgan, Professor of Collective Intelligence, Public Policy & Social Innovation at University College London and Fellow at The New Institute, Hamburg, and Demos Helsinki

Renaissance, the world and Europe

Beyond the obvious

In the middle of the 20th century Europe was ravaged by world war. But it continued to dominate the world. The empires of Britain and France remained vast. Europe accounted for over a fifth of the world’s population and most of its largest economies.By the middle of the 21st century that will all have changed dramatically. Europe’s share of world population will be closer to a twelfth; its economies will have been overtaken not just by China and India but possibly by others such as Brazil and Nigeria. Its military might will be modest compared to the superpowers.

Moreover, many of the things that might have once seemed uniquely European no longer do. There are many examples of healthy democracies and many examples of the rule of law. Science is more generously funded in countries like South Korea or Israel than most of the EU.

To the extent that people across the world talk about European values, they talk as much about slavery, exploitation and genocide as they do about human rights.

So, any discussion of renaissance has to be tempered by humility. Too much European self-love feels ever less appropriate to the times.

Picture above: Geoff Mulgan, Copyright: NESTA

What Europe has however sustained is a unique mix of features that remain attractive to the rest of the world. We remain good at combining security, prosperity, democracy and ecology. In the developing world people speak of “getting to Denmark” as the typical objective for most of the world’s poorer countries.

And part of that mix is being at ease with creativity, exploration and discovery. That hunger for challenge is not only still missing in many places but is also in retreat—squeezed in Xi’s China, blunted in Erdogan’s Turkey, frozen out in Putin’s Russia, ideologically constrained in Modi’s India.

This makes it all the more important that Europe continues to try to imagine, to fuel creative imagination. To me the heart of this is to imagine not just how the world could get to Denmark, or how to assert our values, but rather to think forward to a plausible and desirable picture of what societies could be like a generation or more from now.

What might a truly zero-waste and zero-carbon society look like? How could democracy evolve to make the most of collective intelligence? How can we live with hugely powerful artificial intelligence in ways that help us thrive? How will we live with far more free time, the result of shrinking working hours and rising life expectancy?

This is the imaginative space that is so badly needed now and at the heart of any plausible renaissance. But at the moment, in Europe as elsewhere, the thinking is weak and constrained.

The universities have largely given up on their role in exploration of the future (something I have written about, with suggested remedies, for the New Institute in Hamburg). Political parties and think tanks

are much more trapped in the present. A few governments have small teams looking into the distant future—for example in Singapore and Finland. But in general, although there is heavy investment in technological imagination and futures—much of it in Silicon Valley—there is far less on social possibilities. This is one reason why so much of Europe’s public now fear the future and expect their children to be worse off than them.

I’m interested in the role the arts can play. Claims that the arts can be prophets of the future, trailblazers of a future society, are quite wrong, and based on misunderstanding—though commonly articulated over the last two centuries by everyone from Percy Bysshe Shelley (who called poets the “unacknowledged legislators of the world”) to Joseph Beuys (who claimed that “only art is capable of dismantling the repressive effects of a senile social system that continues to totter along the death-line”). I can think of no work of art of the last 50 years that described or defined a better future for our society.

But what the arts are uniquely well placed to do is other essential work. I believe that some of the methods of creativity and design need to be integrated with the social sciences and the work of policy design. Remarkably little of this happens now—yet that cross-pollination was precisely what fuelled previous renaissances.

The arts can bear witness and warn—as so many are doing in relation to climate change. They can transform our perceptions. They can explore possibilities, both good and bad, as so many are doing with AI and data. And they can help large numbers to take part in the work of social exploration. Here are three examples.

Bearing witness: climate change

Climate change is now the most visible big crisis, prompting an extraordinary range of artistic responses. Most try to bear witness to what’s happening. Olafur Eliasson’s blocks of ice melting in city squares vividly make people think about climate change as a reality, not an abstraction. A similar effect is achieved by Andri Snær Magnason’s plaque to commemorate a lost glacier in Iceland or the World Meteorological Organization’s short videos presenting fictional weather reports from different countries in the year 2050: “WMO Weather Reports 2050.” Others turn the medium into the message, re-using waste materials to signal the emergence of a more circular economy.Literature is also grappling with climate change. What one author called ‘socio-climatic imaginaries’ can be found in novels such as Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife and Kim Stanley Robinson’s Green Earth (both from 2015) which go beyond the eco-apocalypse to examine the multiple interactions between nature and social organisation. Kim Stanley Robinson has spoken of science fiction as “a kind of future-scenarios modelling, in which some course of history is pursued as a thought experiment, starting from now and moving some distance off into the future” and makes a good case that literature is better placed to do this than anything else. As the warning signs of crisis intensify we should expect all the arts to respond in creative ways, both warning and bearing witness but also pointing to how we might collectively solve our shared problems.

Investigating complex challenges

The second big crisis—in the sense of being both a threat and opportunity—comes from algorithms and a connected world. Here the role of the arts seems to be more about investigating complex challenges and dilemmas. Many fear that technology will destroy jobs, corrode our humanity and our ethics. So it’s not surprising that we’re seeing an extraordinary upsurge of art works both using and playing with the potential of artificial intelligence. For some artists AI is primarily interesting as a tool—with GPT3 writing fiction; Google Tiltbrush and Daydream in VR; or the growing use of AI by musicians and composers. There are many wonderful examples of emerging art forms (like Quantum Memories at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne). But others are trying to dig deeper to help us make sense of the good and the bad of what lies ahead. Look, for example, at the work of Soh Yeong Roh and the Nabi Center in South Korea exploring ‘Neotopias’ of all kinds and how data may reinvent or dismantle our humanity. LuYang’s brilliant ‘Delusional Mandala’ investigates the brain, imagination and AI, connecting neuroscience and religious experience to our new-found powers to generate strange avatars.

AI’s capacity to generate increasingly plausible works of visual art and music is of course a direct threat to artists, and perhaps encourages a