Human-Machine Interfaces, intelligent systems and cultural heritage

Maria Giulia Losi, PhD, Project Leader and Interaction Designer at RE:Lab; Silvia Chiesa, PhD, Project Manager in the R&D group of RE:Lab; Annalisa Mombelli, R&D group of RE:Lab, Reggio Emilia

Human-Machine Interfaces, intelligent systems and cultural heritage

Perception might be reality

In today’s context, related to health emergency, some aspects of technological design assume a peculiar role. The first is the theme of distance; the second is the theme of the extension of sensory capacity through digital technologies; and the third is the recognition of the state of the subjects. These three sets of factors, the need to manage distance, the need to extend technological sensoriality into the distance, and the need to recognise in the distance not only the sensoriality but also the state of the user—whether a patient, driver or viewer—thus constitute a new axis of technological design.

Picture left: Interfaccia suono, Copyright: RE Lab

A new anthropocentric setup for technologies

This new axis prefigures the attempt to fill the gaps, the attempt to relaunch an idea of technology that can bring people together, even in this current social framework of difficulty. Therefore, starting from this idea of rapprochement, a new anthropocentric approach to technological performance can be founded, which is undoubtedly one of the central axes of a New Renaissance, based on the integration between the anthropocentric culture of the Renaissance tradition and the potential 4.0 of the technologies mentioned above: those intended to extend the sensory framework; those intended to increase the recognition of the subject and respect of his emotional and cognitive state,; and finally those oriented to extend his ability to live experiences not necessarily in presence.Starting from this premise, RE:Lab, in the framework of the activities of the Emilia Romagna Region, wanted to compose this complex puzzle with diversified initiatives within several projects. First of all, in the midst of the pandemic, the experience of restitution of a phenomenon of intense bodily relations such as dance was sought. Subsequently, the idea of extending the sensory capacity in the relationship, born even before the health emergency took shape, was resumed and developed, and then relaunched during the pandemic experience through the concept of an Atelier, that is, a creative space that takes into account the management of sound manipulation. Finally, we added the idea of including in the processes of technological relations the recognition of the state of the user, not only cognitive but also emotional, so that his emotions allow to recognise the state of use and on the basis of this to orient and design systems of safer and more effective interactions.

A Living Lab for Novel Human-Machine Interactions – A New Grammar for Dramaturgy and Choreography in Digital Space

How can user experience design foster innovation processes in the dance and live performance sector?In a historical moment like the current one, where distance has become one of the hallmarks of experience, the performing arts and dance sector has been put to the test. At the beginning of 2020, the Aterballetto Dance Foundation asked itself some questions:

– Can the emotion of the performance exist without the performance?

– Is it possible for a dance performance to engage the viewer while the dancer is not physically present?

– Is there a safe-conduct to ensure that art can express its expressive power in the absence of contact and in the presence of „distancing“?

In the most uncertain months of 2020, marked by the closure of theatres, the Aterballetto Foundation has managed, through the project Virtual Dance for Real People1, in collaboration with RE:Lab, to imagine a different user experience, through the techniques of Cinematic Virtual Reality and the use of virtual reality visors (such as Oculus Quest).

The design of the user experience has led not only to the creation of a new format for viewers but also to the formulation of a new grammar involving choreographers, interaction designers, and video experts, in identifying a common language and a new way of thinking about choreography. The spectator in fact has been imagined in a central position, in which the viewer can dance together with the dancers.

The search for a relationship of closeness with the spectator has led us to investigate the immersive aspects of technology, also through the use of spatialised sounds, without making the dance abstract: the choreography, conceived for the final technological instrument, remains at the centre of the experience, able to release new and unexpected emotions.

Picture right: MicroDanza Meridiana, Fondazione Nazionale della Danza / Aterballetto, Coreografia: Diego Tortelli, Danzatrici: Casia Vengoechea, Annemieke Mooji, Foto Celeste Lombardi, Technological development and user experience design RE:LAB

Dynamic Mapping—Sound Atelier in distance environments

Many studies have analysed how much music and the sound environment that surrounds us can influence cognitive and linguistic development.How can we investigate, through new immersive audio technologies, the relationship between children and sound, considered as a compositional element of musical language but also of language itself?

From the encounter between engineering research in the area of the spatialisation of sound and the mission of Reggio Children (International Center for the Defense and Promotion of the Rights and Potentialities of All Children), the Sound Atelier2 was born, a laboratory in which children can experiment with a new and complete concept of sound fruition, for which the new child-friendly application EUPHONIA was designed.

The design of the user interface was developed for and with the children, who were involved as design partners to verify their understanding of a 3D interface. In fact, through the support of the figures of the atelierista in collaboration with the designer, it was possible to highlight the difficulties that children had to orient themselves in a virtual environment and a new UX design was redefined for the tablet application called EUPHONIA from the union of the ancient Greek words EU (true) and PHONIA (sound). The app’s interface reproduces the room that houses the atelier in order to give the user an idea of the position of the sound in the space. From a dynamic acoustic library it is possible to choose sounds, associated with representative images, and position them in the space, thus composing 3D soundscapes.

Technological-pedagogical research on sound in space has thus taken its most natural form as the „Atelier of Sound”, an immersive audio environment/laboratory in which children can experiment and dynamically explore the entity “sound“ in all its dimensions.

On the one hand, therefore, it is an expression of the Reggio Emilia Approach, a socio-constructivist educational philosophy based on research and the values of lifelong learning that strongly believes in the dialogue between theory and practice, and sees the child in his relationships with others, as an active part of the learning process. On the other hand, the interest of the multidisciplinary research group in the rendering of sound spatialisation has also approached the concepts of Acoustic Ecology described by the teacher/composer Murray Schafer in his great work The tuning of the world (R.Murray Schaefer, 1985): The soundscape is our acoustic environment, the ever-present noises we all live with. The author suggests that today we suffer from acoustic overload and are less able to hear the nuances and subtleties of sound. Our task, he argues, is to listen, analyse, and make distinctions despite the noise pollution.

The result of this Audio Interaction Lab is a dynamic 3D sound scene whose content and spatial organization is controlled in real time by the children, enhancing their awareness and sensitivity of sound in space.

Picture above: Euphonia, (particolare dell’App, schermata dell’ Area ambiente sonoro), progetto Atelier del suono/Reggio children, Technological development and user experience design RE:LAB

Spillover effects of Sound Design: Increasing driving safety and comfort through the recognition of one's emotional state: from the HU-DRIVE experience to the NextPerception project

Sound Design and its value-added in Human Machine Interaction are not limited to the Cultural and Creative Sectors and Industries—for illustration we review one project in the automotive sector: Several studies in the literature show a strong relationship between emotions and traffic accidents. In fact, negative emotions, such as fear, anger, disgust, or sadness, increase the likelihood of exhibiting dangerous behaviours while driving (Magaña et al., 20203).

In recent years, affective technologies have been developed that offer new opportunities to improve road safety by using the recognition of the driver’s emotions and state, and their regulation through appropriate interaction strategies on board the vehicle. Affective user interfaces are those interfaces that are capable of understanding through psychophysiological measures, conversational analysis, and facial expression recognition human emotions while interpreting, adapting, and potentially responding appropriately (Braun, Weber, & Alt, 2020).4

Within the HU-Drive5 project, the HUman Driver Assistance System presented at CES 2021 in collaboration with the startup Emoj, RE:Lab presents an innovative solution to increase safety, quality and comfort of driving. The HU Drive system, in fact, automatically recognises the driver’s emotional and cognitive state and adapts the vehicle interface in real time.

Novel Human-Machine Interactions based on trust and transparency

Recently, new trends are emerging in the topic of human-computer interaction. In order to achieve better levels of trust in automation, the „negotiation-based“ interaction approach has been studied (Koo et al., 20146; Castellano et al., 2018)7 which consists in providing the user with explanations instead of warnings, in order to increase the transparency of the system.

Taking this line of research as a basis, RE:Lab is carrying out the activity of developing an interface able to adapt to the state of the driver within the NextPerception project. The main objective of the project is to develop a Driver Monitoring System, able to classify both the driver’s cognitive states (distraction, fatigue, workload, drowsiness) and his emotional state (anxiety, panic, anger) as well as the driver’s position inside the vehicle. What can we learn here about the role of culture in digital societies and take spillover back to Cultural and Creative Industries?

In conclusion, RE:Lab’s research activity focused on the design of innovative strategies of interaction with emerging technologies, including artificial intelligence systems that do not want to replace people but put users, at best humanism, at the centre stage to amplify human capabilities.New conceptual models, new strategies, new metaphors will be born in future research about man and machine interaction, making the user more aware of what happens when interacting with these systems, and which are the expression of an interweaving between science and art, technology and cognitive and emotional languages: all elements at the basis of the redefinition of a New Contemporary Renaissance.

References

1 Trailer VIRTUAL DANCE FOR REAL PEOPLE (2021): https://youtu.be/h9u1Cs2GMf8

2 Federica Protti, Simone Fontana, Elena Maccaferri, Claudia Giudici, and Roberto Montanari. 2013. Audio-interaction lab: designing an immersive environment to explore the acoustic ecosystem with a tablet interface. In Proceedings of the Biannual Conference of the Italian Chapter of SIGCHI (CHItaly ’13). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 19, 1–8. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1145/2499149.2499160

3 Magaña, Víctor Corcoba, et al. „The effects of the driver’s mental state and passenger compartment conditions on driving performance and driving stress.“ Sensors 20.18 (2020): 5274.

4 Braun, M., Weber, F., & Alt, F. (2020). Affective Automotive User Interfaces–Reviewing the State of Emotion Regulation in the Car. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.13731.

5 EMOJ & RELAB present HU-Drive @CES2021, the innovative solution presented at CES 2021 by EMOJ and RE:Lab: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SQ_EWRAM23o

6 Koo, J., Kwac, J., Ju, W., Steinert, M., Leifer, L., & Nass, C. (2015). Why did my car just do that? Explaining semi-autonomous driving actions to improve driver understanding, trust, and performance. International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing (IJIDeM), 9(4), 269-275.

7 Castellano, A., Landini, E., & Montanari, R. Un nuovo paradigma di interazione per la guida cooperativa: il progetto AutoMate.

Maria Giulia Losi

Maria Giulia Losi, PhD in „Humanities and Technologies: a research integrated path“. She is a project leader in RE:Lab with many years of experience in the design and development of Human-Machine Interaction systems and EU research projects. At RE:Lab since the beginning of 2011, she has been involved in several projects as Project Manager and Interaction Designer in different domains, from Automotive and Off-HIghway vehicles HMI and IoT Apps to Cultural Heritage interactive exhibitions design. Key publications are reported in the following:

1. Leandro Guidotti, Maria Giulia Losi, Roberto Montanari, Francesco Tesauri, “Motorsport Driver Workload Estimation in Dual Task Scenario”. IARIA Cognitive 2011

2. Daniele Pinotti, Fabio Tango, Maria Giulia Losi, Marco Beltrami. “A model for an innovative lane change assistant HMI”. HFES 2013 Conference Proceedings

3. Corazza F., Snijders D., Arpone M., Stritoni V., Martinolli F., Daverio M., Losi M.G., Soldi L., Tesauri F., Da Dalt L., Bressan S. „Development of a tablet app to optimize the management of pediatric cardiac arrest: a pilot study“. IPSSW2020 – 12th International Pediatric Simulation Symposia and Workshops

Annalisa Mombelli

Annalisa Mombelli, Graduated with a Master’s Degree in Conservation of Cultural Heritage at University of Parma, defending a thesis about the innovation in publishing by Bodoni with his illustrated masterpiece “Epithalamia”. She also graduated in Advanced European Studies at European College of Parma. She worked as a freelance coordinator for private and public cultural projects. Now, she works in the R&D group of RE:lab, following activities in the field of education and culture.

Silvia Chiesa

Silvia Chiesa, PhD in Psychological, Anthropological and Educational Science at the University of Turin, defending a thesis concerning the spatial cognitive abilities in disabled persons. She expanded her activities outside the academic field working in the context of Human-Machine Interaction and more in general in the User Experience Research. She is Project Manager in the R&D group of RE:Lab. Here, she led international projects and activities concerning usability and acceptance assessment, in the domains of transports, household appliances and healthcare.

From the Station of Being to Societal Transformation – How design can drive a new European Renaissance

Ambra Trotto, PhD; Prof. Caroline Hummels; Jeroen Peeters, PhD; Daisy Yoo, PhD; Professor Pierre Lévy Eindhoven University of Technology, National Conservatory of Arts and Crafts

The design and how it came to be

The ‘Station of Being’ is a fully functional, experienceable prototype of a Smart Bus Station in the Northern Swedish city of Umeå that was opened in 2019. The project was initiated by the City of Umeå and partly funded by the H2020 Smart City Lighthouse project RUGGEDISED.

The aim of this design is to make public transport more attractive, to promote an increase in use and, in turn, to lower the carbon emissions of the city. The Station achieves this by affording a positive waiting experience, aiming to turn wai(s)ting time into time to feel, reflect, pause and move: in a nutshell, to be.

Two main components of the design contribute to the passenger’s experience.

– A dynamic light and soundscape informs passengers in or near the station which bus is about to arrive. A subtle play of lights refers to the arriving bus line through its colours, while a soundscape plays to tell stories about the character and history of the line’s final destination. This combination offers ambient information which can be perceived on one’s sensorial periphery, removing the need for passengers to pay constant attention to the coming and going of busses.

– Wooden ‘pods’ hanging from the ceiling provide a physically comfortable place for waiting passengers and contribute to a feeling of safety. The pods can be turned 360 degrees, providing a way to lean and stay out of the wind or just mindlessly sway. The pods allow one to seclude oneself, or to create a social space.

Picture above: Station of Being, Copyright by Samuel Pettersson

The design and development process for the Station of Being followed the Designing for Transforming Practices approach (Hummels, 2021, Trotto et al. 2021), which catalyses liveable ecosystems by transforming existing practices into truly sustainable ones through design. It does so by initiating and curating multidimensional synergies, driven by beauty, diversity and meaning. The scope is to imagine and propose sustainable futures, in which all beings are respected and actions to heal the planet are taken, thus moving towards a horizon of collective thriving. Those futures are populated by people living purposeful lives, in beautiful living spaces.

The design process of the bus station involved a large number and a wide range of stakeholders. The project was driven by the national Swedish research institute RISE in collaboration with a design and engineering consultancy, Rombout Frieling Lab. The project was owned by the Comprehensive Planning Department of the City of Umeå and the Streets and Parks Department acted as a client. The process further involved the Umeå Institute of Design at Umeå University, the public transport company Ultra, the local energy company, Umeå Energi, real estate developers, maintenance workers and engineering and building companies.

Elucidating transformations

Transformation is a substantial change, often associated with innovative and radical change. Transformation occurs when one configuration is converted or changed into another, whereby the change is major or complete (Mirriam Webster Dictionary). We use the term ‘transformation’ when designing for transforming practices (TP) to denote substantial enduring change of values, ethics, and related behaviours of a person, a community or society, triggered by the need of creating alternative ways to engage with the world, addressing specific societal challenges. In this context, people and communities become (and are) transformation itself. This demands a leap, a paradigm shift, even for what seems to be smaller personal transformations (Hummels et al., 2019; Hummels, 2021, Trotto et al. 2021).

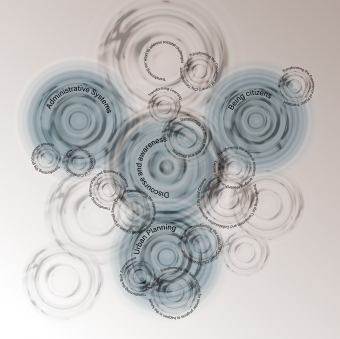

Picture right: Copyright by Ambra Trotto, Caroline Hummels, Jeroen Peeters, Daisy Yoo and Pierre Lèvy

The process that led to the development of the Station of Being spans from the inception of a procurement process in 2017 for its construction to today being a functioning bus station in Umeå. This project triggered different levels of societal transformation grouped around four types of practices, as shown in the figure below. We saw transformations emerging in administrative practices related to the organisational and legal activities and procedures of all parties involved. Moreover, the Station of Being has brought about several transformations in the way one can be an active and engaged citizen, and in the way one can be a responsive municipality and community,

particularly in the domain of urban planning. Finally, it has changed the overarching discourse on how to research, develop and transform smart cities and communities.

Some of these transformations were explicitly intended, some of them emerged unexpectedly along the way and had an impact on the process, and some are indirect consequences of the process that we observed over time. We will elucidate these four practices, by unpacking one illustrative example each, regarding transformations at different levels and scales of the process.

Administrative systems: Transforming the Contract of Collaboration

The procurement was won by a consortium consisting of RISE in collaboration with Rombout Frieling Lab. Following a standard public works building contract, a dense, standardised framework of environmental impact, safety, working environment and other regulations and legal responsibilities were included in the contract. RISE could have developed and proposed a solid and participatory process; however, it was not RISE’s role to be responsible for the building process, neither administratively nor technically. Yet the City could not leave these responsibilities out of the contract. In the end, an agreement was made about which specific responsibilities could be removed from the contract, with the agreement that they would pass on to the builder to be contracted in the future. Working on such innovative projects surfaced the need to change the content as well as the intent of contracts. The project demonstrated an administrative and relational transformation that required mutual trust.

Urban planning: Transforming the notion of “smart cities” development

The original brief included a number of practical and functional requirements, and stated amongst other things that the bus station should: (a) be highly innovative, smart and sustainable; (b) promote a feeling of safety for passengers; and (c) involve citizens in its development. Most importantly, however, special emphasis was placed on the requirement to prevent heat loss from buses when opening their doors to (un)boarding passengers. This is a typical example of a narrowly-defined, reductionist approach to requirements, which can lead to inadequate, mediocre solutions. It was clear to the design researchers that a reframing of the project and requirements was necessary in order to approach the challenge as a ‚wicked problem‘ and come up with innovative interventions.

The first step in this reframing process was taken through a course at the Umeå Institute of Design. About 20 design students carried out design interventions in the city,

looking for meaningful experiences of public mobility. They involved passengers and bus drivers in designing and testing prototypes and mockups. At the same time, the team of designer-researchers found that an indoor bus station was not a viable option. The research showed that such a solution would not reduce carbon emissions, but rather it could lead to a potentially unsafe and difficult-to-maintain facility. The portfolio of design ideas from the students and the design research team pointed in another direction for reducing carbon emissions, namely increasing the willingness of people to use public transport more, by offering a pleasant traveling experience for passengers. Accordingly, the brief and the expectations of the municipality were transformed throughout the design process.

Being citizens: Transforming the Experience of Public Transport

Opened in October 2019—shortly before the pandemic hit—the Station of Being saw an increase of about 40% of passengers in the months following its opening compared to the previous year. Furthermore, the increase doubled compared to other nearby stations. A small pilot field study showed that people generally have positive feelings about the new station, and that the design scored highly with women in particular, due to the sense of safety it evokes (Åström, 2020). The Station of Being is now included in the Umeå Gendered Landscape (n.d.), and is deemed to have positively transformed the waiting experience.

Discourse and Awareness: Transforming learning

The final transformation we highlight here has to do with lifelong learning. The design research team initiated a participatory process aimed at empowering the relevant stakeholders, especially the municipal staff. Their active involvement in the design process increased their confidence in working beyond the beaten track. It reassured them in their leadership capacities and in their ability to participate in transformative processes. A clear example concerns the municipality’s snow ploughing service. Umeå is a town in northern Sweden that experiences heavy snowfall during several months of the year. The service was initially sceptical about how the design team might consider their needs. However, during the process they were able to regularly test how the bus station could be easily cleared of snow using machines, rather than the existing manual methods at traditional bus stops. The process increased their motivation, commitment and enthusiasm.

Design for Transforming Practices for a new European Renaissance

We are facing major societal challenges that call for multifaceted transformations, as illustrated by the example of Station of Being, including political, economical, social, technological, legal and environmental factors (also indicated as PESTLE) as well as demographic, ethical, ecological, intercultural, organisational and digitalisation factors (e.g. labeled as STEEPLED, DESTEP and SLEPIT) (Helmold & Samara, 2019). The escalation of tensions in our connected society—and the rebellion of the planet that has been exploited without any respect for its balance and the rights of all those inhabiting it—urgently demand new ways of working, fuelled by alternative value systems that are different from the status quo. These new ways of working together and inhabiting a planet in need of healing require transformations toward practices of mutual care, of repairing, experimenting, making and unmaking together. The Station of Being exemplifies some of these transformations.

The approach that we use in projects such as RUGGEDISED is known as Designing for Transforming Practices, in short TP (Hummels et al. 2019). It is an approach, or rather a quest to engage with the world in co-responsible ways, by transforming the status quo and developing new alternative practices (Hummels, 2021). TP catalyses liveable ecosystems by “transforming existing practices into truly sustainable ones, through design. It does it by initiating and curating multidimensional synergies, driven by beauty, diversity and meaning. The scope is to imagine and propose sustainable futures, which are those futures where all beings are respected and actions to heal the planet are taken, towards a horizon of collective thriving. Those futures are populated by people living purposeful lives, in beautiful living spaces” (Trotto et al. 2021).

This approach is founded on five principles: complexity, situatedness, aesthetics, co-response-ability and co-development. TP is not about ‘solving’ the problems, but about ‘dissolving’ them by using design to explore and imagine futures and concretising them in the here and now to experience the alternatives. TP stimulates critique, elicits dialogic debates that arise from tensions between the status quo and

alternatives, and finds new avenues for the flourishing of a new civilisation. Only from new practices can a new civilisation, and hence a new renaissance, arise (Trotto, 2011).

The process of the Station of Being underlines the ability and competence of designers to deal with ‘wicked’ problems, i.e. messy, complex problems which cannot be tamed or solved (Rittel & Webber, 1973). Designers have the attitude, skills as well as methods to deal with complexity and to tackle complex problems pragmatically. The quality of design and designers is that they can reframe and reconfigure challenges with the aim to dissolve them in the long run. With TP, we do not only aim at dissolving wicked problems, but we also focus on impacting future trajectories by changing attitudes and practices of involved parties, breaking boundaries between silos and addressing organisational aspects, as shown in the Station of Being.

Not only are they highly complex, but also our societal challenges carry a strong sense of urgency, asking for immediate actions. Hence we are bound to take actions

in the here and now while simultaneously generating a long-term outlook for both the future and history (100 years and more), thus connecting past, present and future. By working on several time scales at the same time, we prepare ourselves for serendipity, emerging outcomes and wicked impact. Above all, we do so by engaging with a broad spectrum of stakeholders to evoke co-response-ability.

With TP we want to contribute to a European Renaissance. In this new era, we are inspired and empowered to collaboratively explore processes and practices founded on care, trust and repairing. To be

able to contribute even better to a European Renaissance, we have recently made an exciting new step in our quest and established the Design Competence and Experience Centre, which “exists to catalyse ecosystems and transform existing practices into more sustainable ones, by initiating and curating multidimensional synergies, with beauty, diversity and meaning, for sustainable futures” (Trotto et al, 2021). It is an endeavour in which creativity can lead the ways (as opposed to “the way”) to unlock ourselves from old paradigms that lead to the depletion of the planet and of humankind. We invite you to join the quest for ushering in a European Renaissance.

REFERENCES

Åström, M. (2020). Innovations in Urban Planning: A study of an innovation project in Umeå municipality (Dissertation). Retrieved December 02, 2021, from http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-171983Helmod, M. (2019). Tools in PM. In: M. Helmold and W. Samara (Eds). Progress in Performance Management: Industry Insights and Case Studies on Principles, Application Tools, and Practice, Springer. p 111-122. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20534-8_8

Hummels, C. C. M., Trotto, A., Peeters, J. P. A., Levy, P., Alves Lino, J., & Klooster, S. (2019). Design research and innovation framework for transformative practices. In Strategy for change (pp. 52-76). Glasgow Caledonian University.

Hummels, C. (2021). Economy as a transforming practice: design theory and practice for redesigning our economies to support alternative futures. In: Kees Klomp and Shinta Oosterwaal (Eds). Thrive: fundamentals for a new economy. Amsterdam: Business Contact, 96-121.

Rittel, H. W., & Webber, M. M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy sciences, 4(2), 155-169. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01405730

Trotto, A., Hummels, C. C. M., Levy, P. D., Peeters, J. P. A., van der Veen, R., Yoo, D., Johansson, M., Johansson, M., Smith, M. L., & van der Zwan, S. (2021). Designing for Transforming Practices: Maps and Journeys. Internal publication. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven.

Umeå Gendered Landscape (n.d.). About the gendered landscape. Retrieved December 02, 2021, from https://genderedlandscape.umea.se/in-english/.

Ambra Trotto

Ambra is the Design and Research Director of the European Design Competence and Experience Center for inclusive innovation and socetial transformation and associate professor at the Umeå Institute of Design.She leads the Digital Ethics initiative at RISE, directing the strategic work regarding how RISE supports societal actors in taking ethics into account, when designing transformation with technology as a material. She is part of the RISE Development Team of the strategic research area Value-shaping System Design. She has initiated the environment of RISE in Umeå, leading The Pink Initiative, which is establishing, through design research, local, national and international multidisciplinary ecosystems, supporting business and society to thrive and create sustainable futures. Ambra has 16 years experience in writing and participating in various forms of European projects. Ambra Trotto’s fascinations lie in how to empower ethics, through design, using digital and non-digital technologies as materials. Strongly believing in the power of Design and Making, Ambra works with makers, builders, craftsmen, dancers and designers to shape societal transformation. Within her design research activity, she produces co-design methods to boost transdisciplinary design conversations. She closely collaborates with the Research group of Systemic Change and the Chair of Transforming Practices of the Department of Industrial Design at the Eindhoven University of Technology.

Jeroen Peeters

Jeroen is a Senior Design Researcher at the unit Societal Transformation, part of the department Prototyping Societies at RISE Research Institutes of Sweden. Within this capacity, he has contributed to a variety of national and international research and design projects with public and private sector actors. Since 2021, he is also a visiting researcher at the Systemic Change Group at the Department of Industrial Design at Eindhoven University of Technology. Jeroen´s research work focuses on how to design for engagement and the use of design methodologies to develop insights and knowledge of complex societal challenges. This work is centered around the design of proposals that make societal transformation experienceable with the aim of allowing stakeholders to feel and thereby understand what is necessary for a transformation to take place. Jeroen holds degrees in Industrial Design from Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands (2012) and a PhD in Design Research from the department of Informatics at Umeå University in Sweden (2017).

Picture © Murat Erdemsel

Caroline Hummels

Caroline Hummels is professor Design and Theory for Transformative Qualities at the department of Industrial Design at the Eindhoven University of Technology (TU/e). Her activities concentrate on designing for and researching transforming practices. She is linking nowadays challenges and complexities of quintuple helix partners, with probably, plausible, possible and preferable futures in the upcoming 5 – 100 years, through designing alternative ways to engage in complex socio-technical systems. She is thereby interweaving theory and practice, by developing with her team a design-philosophy correspondence, in which both disciplines mutually inform each other to address societal challenges.Caroline has always worked at the forefront of design research to develop the discipline, push its boundaries and address societal challenges. She is co-founder and steering committee member of the Tangible Embedded, and Embodied Interaction (TEI) Conference. She has been at the forefront building the Research through Design (RtD) field and community in the Netherlands. She is ambassador for co-creation and participation of the Key Enabling Methodologies (KEMs) for mission-driven innovation, advisory board member of the Dutch Design Foundation, associate editor of the Journal of Human technology Relations, and editorial board member of the International Journal of Design. Picture © Marike van Pagée

Pierre Lévy

Pierre Lévy is professor at the National Conservatory of Arts and Crafts (CNAM) in France, holder of the Chair of Design Jean Prouvé, and researcher at the Dicen-IDF lab. He is interested in the correspondence between reflection and design practices, pointing towards transforming practices and sciences. His research mainly focuses on embodiment theories and Japanese philosophy and culture in relation to designing for the everyday. Previous to his position at CNAM, he has been researcher at the University of Tsukuba and Chiba University in Japan, and assistant professor at Eindhoven University of Technology. He holds a Mechanical Engineering master’s degree (UT Compiègne, France), a doctoral degree in Kansei (affective) Science (University of Tsukuba, Japan), and a HDR in Information and Communication Sciences (UT Compiègne, France). He is also co-founder and former president of the European Kansei Group (EKG) and coordinator of the Kansei Engineering and Emotion Research (KEER) Steering Committee.

Picture © Nami Lévy

Daisy Yoo

Daisy Yoo, PhD, is an assistant professor at the Department of Industrial Design at the Eindhoven University of Technology in The Netherlands. Her primary research focus is on designing for public services and social sustainability. In her prior work she investigated issues of participation, inclusion/exclusion in politically contested design spaces – spanning from local issues concerning the co-design of public transportation service to global issues concerning the transitional justice for Rwanda in the aftermath of the 1994 genocide. Such work, entangled in the web of complex social dynamics, raises methodological and ethical challenges, calling for new design methods, toolkits, and theories. Prior to TU/e, she held the postdoctoral fellowship on participatory design at the Aarhus University in Denmark. She holds a PhD in Information Science and Human-Computer Interaction from the University of Washington, where she was advised by Batya Friedman of the Value Sensitive Design Lab. She received her Master’s in Interaction Design from Carnegie Mellon University, and her Bachelor of Science in Industrial Design from Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST).

Picture © Vincent van den Hoogen

physical-virtual-virtual-virtual-physical-physical-virtual-physical-physical-virtual-physical-virtual-virtual-physical-virtual-virtual

Alejandra Panighi, Strategic Consutant at Mediapro, Madrid

physical-virtual-virtual-virtual-physical-physical-virtual-physical-physical-virtual-physical-virtual-virtual-physical-virtual-virtual

In which metaverse do we want to live?

The Metaverse—A ubiquitous, synchronised universe where presence and sense of presence become indistinguishable.

For those of us who were born in the 20th century, the word „metaverse“ came to be associated with science fiction books and films of the 1990s which depict a dystopian future dominated by technology. In most of them, humanity is dominated by mega corporations, totalitarian governments or dehumanised scientists who use simulated worlds and robotic environments to subject people to situations of oppression, domination and injustice.

But for those who grew up with the online world as an integrated space within the physical world, the metaverse is simply a collection of all the virtual universes that coexist in the cloud and are necessarily shared, interactive, immersive and collaborative.

The metaverse is, for this generation, understood as an environment where the digital assets become an extension of the physical assets—precisely a moment when the blurring of this distinction simply happens.

It began perhaps with the mobile internet, and just accelerated with advances in the use of AR (Augmented Reality), VR (Virtual Reality) and AI (artificial intelligence) until becoming an increasingly present and ubiquitous mixed reality.

Creative industries, particularly video games, went deep into this concept of real-digital and digital-real, making immersive experiences a language of a generation who learned to live and enjoy these environments in which the physical person and its own digital extension coexist and converge.

It is now the same generation that expects to integrate into this metaverse all the other aspects of their lives: sports, social activities, academic life, travel, work and global economy.

For several years, the narrative about this metaverse, as something real outside of films and books, was captive of those who worked to revolutionise the actual rules of Internet, developing the virtual economy from different but close perspectives. It was almost a cryptic universe, accessible to those who could quickly understand the token economy and its fungible and non-fungible tokens and the rules of permissions and permissionless environments—among many other concepts—in which „old“ inventions like Napster would have been unstoppable.

That is until 2021, when Facebook divested itself of its original brand and became Meta by announcing multi-million-dollar investments in augmented and virtual reality, robotics, high-tech VR glasses and sophisticated software applications to make the old Facebook social media network an environment for communication, fun and work in the metaverse.

Other giants of the internet 2.0 era such as Google, Microsoft or Apple also unveiled their plans to develop virtual environments with huge investments. This sudden trust in the virtual economy became a fillip for hundreds of start-ups who could suddenly access a flood of money in projects that few months ago previously have been considered extremely risky. How quickly and how much further it might go is yet to be seen, but lots of ethical questions are raised when we think about a near future where both worlds, the Physical and the Virtual, get together and shape our lives in a constant physical-virtual-virtual-virtual-physical-physical-virtual-physical-physical-virtual-physical-virtual-virtual-physical-virtual-virtual dialectic.

There are at least two main visions of how this Metaverse should be…

One is inherited from the current model of society, led by closed platforms and Big Tech that are not necessarily the bad boys of so many dystopian novels. But there are indeed few and dominant players of the digital economy of the 21st century. They claim the central role such huge machines should be allowed to have, to make this Metaverse happen in an ordered and controlled way, far from actual wilderness of the internet sphere that includes the worst we can see from ourselves in the deep and dark web.

Another vision, in stark contrast, talks about an Open Metaverse created with open technology and open protocols that allow increasingly decentralised and accessible environments for almost anyone. This is the vision of those creators of—and believers in—Web 3.0, which has been evolving for at least 10 years. They advocate for an Open Metaverse based on principles of digital sovereignty and easy access to data and protocols for people to achieve a new world economic order, an order perhaps better, perhaps fairer, perhaps more promising for those who now lie at the bottom of the actual world’s economy.

A third vision, probably the most plausible one, is a coexistence of both centralised and decentralised visions, convergent and divergent environments in which any kind of ordering or regulation will be complex but might prove necessary.

In any case, during the next few years we will experience a true ethical, moral, ideological and economic revolution that is somehow reminiscent of the profound change in society that took place during the Renaissance.

In these times, we will see the scaling of this virtual-based economy, environmental challenges, not only those arising from the digital economy but also those inherited from the current economy, new jobs and the transition between the old jobs and the new ones, and so many other challenges and so many inconsistencies in the meantime.

We’ll need to go through a deep revision of the grounds of Internet, the deepest since it was born:

– the whole process of capture and control of data

– the cost of electricity or other renewable power sources

– accessibility to digital resources

– the conversion from actual sleeping goods in Cloud wallets to the commercial retail system

– the backend of the internet (hardware and software)

– the actual network and nation-based technical infrastructure

– operating systems.

… And so many other concepts raising from the revision of these basic ones.

But also, rethinking what identity means, what belonging means. What is a community? What is fandom? Or random? The possibility of

multiple identities for each person—physical and digital—and a possible total sovereignty for each opens up an unexplored universe.

The sovereignty of identity in the physical world, in the virtual world and in what emerges from the combination of both universes for future generations may completely change social relations in the decades to come.

Somehow, once again, as in Europe’s First Renaissance, the New Renaissance will be all about the convergence of Culture, Economy and Technology.

Alejandra Panighi

Born in Argentina, she started her career in TV in America as producer and journalist, but she was always attracted by all ways of storytelling in almost any written or visual formats too.So it was not a surprise when, in early 90’s, she joined the team that launched Yahoo and AOL portals in the American continent, when they were still a web directory of content curated by people. She experimented with live shows and live interviews with musicians, interacting also with those the few users who could access dial up connections for several minutes. Living in Europe for the last 20 years, she’s been focused in innovation of the film, series, live sport and eSports industries, looking for different business models and new ways of reaching audiences. She embraces technology as a driver for innovation and follows consumer’s behaviour with passion. From VR-XR to immersive experiences, from data management to AI and moving now in the arena of virtual economy her wide expertise on the evolution of the Audiovisual industry is an asset. Focused in EU policy for the last decade, she lives in Brussels and works as a strategic consultant for Mediapro Group, dealing directly with the Board of Directors.

Picture © Pepe Encinas (Barcelona, Spain)

Digital transformation as a second renaissance?

Prof. Dr. Dr. h. c. Julian Nida-Rümelin, Staatsminister a.D., Director of Bavarian Institute for Digital Transformation and Vice-Chair of German Ethics Council, Munich

Digital transformation as a second renaissance?

Towards digital humanism

The European Renaissance began first in Italy after a period of exhaustion by plagues, misery and wars. In the mid-14th century, the plague had plunged Europe into one of the worst catastrophes of mankind, an incurable disease that brought great pain to those afflicted and usually a quick death. Even before the plague, a long-lasting famine had taken hold, for which climate change in the form of significantly falling temperatures probably played a decisive role. The structures of social order eroded and everyday life became brutalised. The population declined markedly, with the paradoxical effect of a valorisation of human labour and an increase in productivity brought about by new technologies. The European Renaissance was preceded by a creeping decline in the authority of clerical and princely authorities, and was characterised by a return to ancient thought, especially that of the Greek Classical period and the Roman Empire. Aristotle was disposed of—prematurely—because the Thomasian worldview, unlike patristics, was based on his writings and had made them the authoritative source alongside the Holy Scriptures.

The young intellectual Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494), born into high wealth and highly gifted, published his writing De hominis dignitate (Rede über die Würde des Menschen EA: 1496) and ensured that it was discussed throughout Europe by intellectuals and eventually also by ecclesiastical authorities. At the centre was an image of God that endows man with artistic creativity, technical innovation, and scientific research; indeed, one might say that in this writing Pico della Mirandola anticipated the thesis of the analytical philosopher Roderick Chisholm that man, like God, is an unmoved mover (Die menschliche Freiheit und das Selbst (1964), S. 82). Human creative spirit completes the work of God. Humans as rational beings are authors of their own life. They are free and therefore bear responsibility for everything they do. Only Immanuel Kant thought the consequences to the end in his practical philosophy of autonomy.

The Renaissance was an epoch of impressive innovation. And like other innovative periods in human history, it was characterized by the breaking up of schools and conventions, by interdisciplinarity, and by the fluid transition of philosophy, science, technology, and art. Education was no longer the learning of preconceived patterns of thought and practice, but self-education with the goal of life-authorship. Leonardo da Vinci did not know whether to see himself as a scientist, technician or artist. The Renaissance cities became documents of impressive design in the combination of technology, craftsmanship, art and science.Are we on the threshold of an era of comparably far-reaching innovations, shaped by the potential of digital technology? To be able to assess this, we first have to face a sobering fact. The third wave of digitisation has not yet made a significant contribution to either labour-hour or resource

productivity. The platformisation of the economy has reshaped it to some extent and created large tech giants, but it has not stimulated growth, or at least not noticeably. In a ranking by the World Economy Forum a few years ago, Germany landed in first place among the most innovative countries in the world—probably to the surprise of the authors—while at the same time being one of the most digitally backward. Working hour productivity in Germany is almost a third higher than the EU average while almost all European countries are outstripping Germany in terms of digital transformation. The productivity of the German economy is just behind Norway and Switzerland, but well ahead of France, Canada, the U.S. and Japan (which leads the East Asian countries). The productivity boost that digitisation triggered with the introduction of personal computers and the use of the Internet in the 1990s has not been repeated in the third wave. At the same time, however, the world is in dire need of a technologically-driven increase in productivity in the face of resource scarcity, ecological depletion and climate change.

All the inadequate efforts to cut CO2 since the 1990s have been far outweighed in Europe by the additional CO2 emissions of the Chinese economy. Meanwhile, the Chinese economy is polluting the atmosphere with climate gases at a higher rate than the US and Europe combined—even though China’s economic output ranks only third after the US and after the EU. If other current and future boom regions such as India or sub-Saharan Africa follow the development path of China, the climate catastrophe in large parts of the world cannot be stopped. The digital transformation must enable other development paths and use human and natural resources far more sparingly without stifling economic momentum in a development phase where the demographic dividend pays off in the global South.

Inventiveness, interdisciplinarity and creativity—the human ambition to master the existing challenges and not to be driven by apocalyptic fears into helpless protest or resentment-laden apathy—are required. A rapid changeover to climate-neutral and ecologically sustainable economic activity, first and foremost in the highly industrialised countries, the treading of new technological, economic and social development paths in fair cooperation between the world’s regions and the mobilisation of human resources in order to overcome the major challenges facing humanity will only be possible with the massive use of digital technologies.

Not data thriftiness, but protection of personal rights and use of data for humane progress in medicine, natural science and education, in state administrations, small and medium-sized enterprises, the efficient and effective organisation of social cohesion, are indispensable for this. The humanistic ideal of human authorship, self-education and creative power must experience a renaissance under digital auspices.

Responsibility remains solely with human actors. Software systems, highly developed so-called „autonomous“ ones as well as those which are called „artificial intelligence“ (AI), are not actors, not people. Man does not become God, who creates other individuals in his image to use them at will for himself. They are merely technical, albeit highly sophisticated, tools that we should use individually and collectively, legally framed and politically shaped, for the good of humanity. This is the central message of Digital Humanism: machines are not people and people are not machines. The currently fashionable AI animism is unscientific mumbo jumbo, a projection of a familiar type that animates the unsouled and gives satisfaction to the swashbucklers. And man is not a machine, not an algorithm-controlled software system, but a freely responsible actor of his actions. Digital technologies will not relieve him of this responsibility, but neither will they take away his freedom to individually and collectively shape life and its conditions.

The renaissance of digital transformation is based on the empowerment of human authorship, on the development of human creativity, on the targeted, intelligent and measured use of new technologies for human purposes. It aims to humanise the world of work through sustainable production and the establishment of fair practices in the global economy, while the current development path has established monopoly structures in the form of large tech giants, shifted greater parts of economic value creation to platforms and made a successful business model out of the skimming of user data from digital service offerings for marketing purposes. This humanistic form of digital transformation will not be feasible without a state framework in the form of digital infrastructures, without an independent European path of „human centred AI“ and transparent uses while safeguarding informational self-determination rights, without a European legal framework of digital dynamics. But the chances are good that the humanistic form will ultimately prevail over the commercial model of Silicon Valley and the state control model of China and other autocratic and totalitarian states.

Prof. Dr. Dr. h. c. Julian Nida-Rümelin, Staatsminister a. D.

Julian Nida-Rümelin teaches philosophy and political theory at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich.JNR was a member of the first Schröder cabinet as Minister of State for Culture and Media. He is a member of the Academy of Sciences in Berlin and the European Academy of Sciences, director at the Bavarian Institute for Digital Transformation (bidt). In 2016, the Bavarian state government awarded him the medal for special services to Bavaria in a United Europe. In 2019, he received the Bavarian Order of Merit. Since May 2020, he has been a member (as deputy chairman) of the German Ethics Council. In 2016, Humanistische Reflexionen (Humanistic Reflexions) was published by Suhrkamp. In the fall of 2018, he published a monograph on Digitaler Humanismus: Eine Ethik für das Zeitalter der künstlichen Intelligenz (Digital Humanism: An Ethics for the Age of Artificial Intelligence) (Piper Verlag), for which he received the Bruno Kreisky Prize in Austria for the best political book of the year. In spring 2020, edition Körber published Die gefährdete Rationalität der Demokratie (The Endangered Rationality of Democracy) and DeGruyter Eine Theorie praktischer Vernunft (A Theory of Practical Reason). Picture © Diane von Schoen

New Stages for Collective Imagination

Annette Mees, Artistic Director of Audience Labs, King’s College London and Creative Fellow at WIRED, London

New Stages for Collective Imagination

The show must go on

Cultural institutions the world over collectively seek out new ways to connect meaningfully to local, global and diverse audiences—To co-produce and programme new kinds of experiences created with new kinds of creative teams and new kinds of partners offers exciting opportunities. Audiences are eager to connect with both big ideas and one another and have challenging and new experiences ahead. Audience Labs is an artist-led initiative looking at the intersection of Performance, Innovation and Social Change and was born at the Royal Opera House in London’s Covent Garden, a location with a centuries-old tradition of performance. Introducing the creative practices of opera and ballet to immersive technologies provided a unique opportunity to look at bringing human emotion and collective experiences together. We want to look at what is possible but always continue to ask what is desirable and in what way technology enriches our life in the wider societal shifts and upheavals of the digital and green transformations taking place before our eyes.

I’m a theatremaker not a technologist. I work in the arts because it has a public function—it’s a space to collectively reflect and imagine, a space that can help us explore what it means to be human in a future society and what it can contribute towards a next Renaissance. I’m interested in the artistic potential of technology and the role art and culture can play in shaping our relationship to the world, to each other and to the technologies we use in that process.

Picture above: Current, Rising CGI Production Shot House of Subconscious, Copyright: Joanna Scotcher & Figment Productions

Current, Rising: an opera in hyper-reality

One of the projects Audience Labs presented in 2021 was Current, Rising. Described as the world’s first ‘hyperreal’ opera experience, it invites audiences to step into an atmospheric virtual world and take centre stage in the performance.

When I joined the Royal Opera House I was inspired by the ‘epicness’ of opera, the way the storytelling was driven by music first, narrative is secondary, the events are there to support the ideas and emotions. So many of them are about heightened emotions, to let you feel all the feels, so to speak, everything is bold and big. In opera the word Gesamtkunstwerk is used, or „all-embracing art form“.

Hyperreality combines Virtual Reality with a physical set and visceral effects like wind, heat, touch and movement to create a multi-sensory, immersive experience. It uses tracking to create a shared experience—the audience can see each other in the virtual space. It felt like an inherently operatic medium, which could enable audiences to step into an imaginative universe and to be the lead characters in it.

We wanted to do a project like this because it allowed us to use the possibilities of hyperreality to expand the idea of what an opera can be, both in the process of creation and in the audience experience. We set out to challenge the traditional hierarchies of opera and searched for different approaches to creating a 21st-century version of a Gesamtkunstwerk: A challenge and change of hierarchy to be found in many sectors, markets and communities now on their way to invent new sustainable and green ways of living and working. For us Current, Rising puts the opera as an institution right in the middle of these transformational debates about possible futures in Europe.

Fellow Travellers

Our starting point for projects is always identifying the most interesting questions—often that is a ‘What If’ question. The immediate second step is casting the right people to explore those questions with. Exploration and innovation is not something one does on one’s own. We believe that the power of creativity and innovation grows exponentially with the diversity and multiplicity present within a team. It is most powerful when based on a shared vision, shared vocabulary. When we visited Figment Productions, their technology and creative team felt like a perfect match. They had a radically different background from us, making work for theme parks and big live events, but they shared our enthusiasm for radical new ways of working, deepening the audience experience and doing everything with imagination. They, like us, were curious about the potential of a hyperreal opera and equally important brought a real sense of technological poetry to the table.

We brought together a highly-experienced and diverse creative opera team. We facilitated a series of sessions where we explored opera and hyperreality, finding directions of travel that might unlock something exciting. I call this establishing the artistic nucleus. Since we were not only inventing what a hyperreal opera might but also how we make it, we needed a space to develop a vocabulary before going into production. We gave makers time to develop attitudes and taste before landing on what they wanted to say on that particular stage; we enabled technologists to find artists that inspired and pushed them in new directions. It was the equivalent of making rough sketches before you decide what the painting looks like.

Picture right:

Iterate

Audience Labs embraced iterative working as a way to try out new ideas, and to de-risk investment and learning. When trying to create something both artistically valuable and highly innovative, you need time to fail and learn, reassess, make changes and try a different approach. Many projects start with an inkling of the possible but need time to gather the right ideas and the right team to work towards something that has meaning and value to an audience. Although an overemphasis on efficiency stifles innovation, iteration is simultaneously the most efficient way to look after your money. Innovation is inherently risky and unpredictable. But by working in stages, starting small and slowly scaling up to full production, you de-risk investment that is necessary for large-scale productions.

Current, Rising used techniques from theatre, technology and design to create a process that allowed the artistic and technological developments to iterate together towards a meaningful piece of work.

We started on paper, trying ideas and concepts out by making simple sketches, storyboards and mock ups. Some of the places we borrowed from included:Theatrical rehearsal and devising techniques

– Game design

– VR production pipeline

– Double diamond model

– Experience design

We shared work often and openly between the team until we knew we had the right story, technology, aesthetic and approach for the project to soar. Only then did we go into the full expensive production period. This approach allowed us to adapt to the complexities as the project grew and deliver an extraordinary project on a tight budget.

The show

The show that emerged from this process was Current, Rising. Inspired by the liberation of Ariel at the end of Shakespeare’s Tempest, Current, Rising takes four people at a time on a journey through the six phases of the night. Participants are empowered to collectively explore a series of imaginary dreamscapes, travelling from twilight to dawn as they encounter ideas of isolation, connection and re-imagination. It explores freedom as a process within our control, rather than as a state in which we exist, and asks how we might harness personal responsibility to join with others to re-think the future.

The audience enter a real life theatre set wearing VR headsets and go on a dreamlike journey carried musically by a poem layered in song. It takes the epic, music-driven and poetic qualities of opera and combines it with the possibility of VR to create any possible landscape, defying all natural laws, pushing beyond what is possible on the stage. In Current, Rising music, the visual world and the physical experience are completely enmeshed, changing the relationships between the creators, the usual sequence of creation, and the relationship of the audience to the work. Here the audience members are the protagonists: they are inside the work, and their physical experience is a part of the work itself.

The audience and the response

An audience research conducted by Royal Holloway discovered fascinating results.It brought new audiences to opera: 31% had not been to the Royal Opera House before and 68% of these new audiences were under 35.It also brought new audiences to the technology: 32% had not experienced virtual reality before. A lot of those were regular opera goers.

Many reported on a potent emotional experience, with uniformly high enjoyment ratings (an average of 4.6 out of 5) with an equally high rating in the seasoned opera goers and VR users and first timers. That cross-pollination of different audiences is really exciting—people who wouldn’t meet each other under different circumstances shared an experience in this show.

An audience research conducted by Royal Holloway discovered fascinating results.It brought new audiences to opera: 31% had not been to the Royal Opera House before and 68% of these new audiences were under 35.It also brought new audiences to the technology: 32% had not experienced virtual reality before. A lot of those were regular opera goers.

Many reported on a potent emotional experience, with uniformly high enjoyment ratings (an average of 4.6 out of 5) with an equally high rating in the seasoned opera goers and VR users and first timers. That cross-pollination of different audiences is really exciting—people who wouldn’t meet each other under different circumstances shared an experience in this show.

Possible futures through art

Current, Rising is one of many projects we developed at the Royal Opera House. In our three-and-a-half years there we worked with 22 partners and 44 artists spread over 14 countries. We explored a range of technologies including game engines, motion capture, animation, augmented reality and virtual reality and worked with artists working in opera and ballet, visual art, music, design, digital art, make-up and filmmaking. This convergence of perspectives, practises and ideas provided an incredibly fertile ground on which to create new ways of thinking about art and new possibilities for creative expression.

Art can make a world worth living in. After shelter, equality, equity and a healthy planet, there is art. Audience Labs explores possible futures through art—we aim to construct shared experiences and transformative moments that enrich people’s lives.At a time when we’re all struggling with what the future holds, we wanted to bring makers and audiences together to imagine a shared future, reflecting collectively on: Where shall we go? How do we want to feel? What do we want the world to look like? We are interested in expanding where culture takes place, and broadening who it is for, who gets to make it and how it interacts with other agents of connection and change in the world in the Next Renaissance

As Audience Labs is starting its time at King’s College London, we will be working with a network of industry experts, collaborators and experts to focus on critical questions surrounding the future of performance.

Picture left: Current, Rising CGI Production Shot House of Subconscious, Copyright: Joanna Scotcher & Figment Productions

The work will focus on four strands:

1. Artistic Futures—how do we make good and meaningful art that both explores new opportunities for connection and rising to the challenges of an uncertain world? This includes inclusive international collaboration, remote creative processes, audience and community engagement, and new partnerships.

2. Cultural Metaverses—exploration of technical infrastructures needed to create and deliver a distributed cultural experience, including distribution models, and digital dissemination, expansive audience engagement and business models.

3. Ethics, Audiences, Diversity and Inclusion. As we move towards new possible futures for art and culture in a hybrid age, we need to support work that promotes a more equitable ethical world for all.

4. Towards a Net Zero Profile. We will explore the use of digital and physical green innovations that promote reduced travel and touring, and will support the development of low/no impact stages, and the green venues of the future.

Initially, in this new context at King’s, we will take the opportunity to convene a wider ecosystem of artists and cultural organisations, technology partners, researchers and students to explore these questions and lay out possible methodologies and projects to start that journey. A practical plan on how we work together to innovate and make great art with ethics, equity and inclusion at the heart.

We don’t have all the answers yet. I see the role of Audience Labs as a place that combines conversations with practical artistic production—an intersection that a Next Renaissance cannot do without. Audience Labs might well be understood as a Renaissance sandbox in exploring and R&D-ing how culture can help understand the ethical side of technology, how culture can push the envelope.

Innovation is constant iteration, a form of continuous thinking, trying and pushing. Artists and arts institutions need partners that share their civic values to enable innovation. Only in value-based and wide-ranging partnerships can the arts create value, change and equity for audiences and communities everywhere: a societal Gesamtkunstwerk or in other words, social cohesion in the transformations ahead of us.

Picture right: Current Rising – set design by Jo Scotcher, Copyright: Johan Persson

Annette Mees

Annette Mees is an award-winning immersive theatre director known for her innovative, interdisciplinary, experiential work that allows audiences to explore big ideas and meaningful change. She is the Artistic Director of Audience Labs; a hub for imagination exploring new forms of theatre and technology to dream up sustainable, diverse and equitable futures. It connects artists, technologists, researchers, experts, communities to spark new thinking. We use centuries of stage craft and the possibilities of cutting-edge technologies to create spaces for radical imagination, emotional connections and collective experiences. Audience Labs started at the Royal Opera House and recently moved to King’s College London to explore the underlying questions emerging around these new forms. We want encourage work by interdisciplinary, diverse and inclusive partnerships that is driven by imagination and equity, works towards net-zero and uses technological possibilities ethically. Next to that she works as an innovation strategist, artistic advisor and dramaturg for a range of organisations and projects. Currently she is the chair of FutureEverything, a co-host of global conversation around the future of culture supported by Arup and Therme, an artist mentor for CPH:DOX and developing a strategic R&D project with Substrakt.

Picture © Annette Mees

Connecting people and places

Susa Pop, co-founding director of Public Art Lab and Connecting Cities Network; Martijn de Waal, professor at the research group Civic Interaction Design at Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, Berlin

Connecting people and places

Why Cultural Led Urban Developments are necessary for Resilient Cities

Placemaking is a global civic trend in urbanism. However, a novel combination of arts, technology development and processes of urban governance empowers placemaking to be responsive and forms an essential contribution to a next renaissance of global cities. Not necessarily by making them less global as the following case studies show, but by bringing in a perspective of interconnected local publics and public values to urban policy, from the design of public spaces to the organisation of urban resource management and carbon-neutral cities.

Picture above: Digital Calligraffiti 2017-21 commissioned by Public Art Lab in cooperation with the artists Michael Ang, Don Karl and Hamza Abu Ayyash, Copyright by Michael Ang and Public Art Lab

Responsive Placemaking

Our cities take shape through the overlap of various ‘scapes’: spheres of the circulation of people, resources, ethnoscapes, mediascapes, financescapes, ideoscapes and technoscapes.1 The rise of new technologies and their accompanying practices in the past quarter of a century—from budget airlines to the internet—has intensified the flows in these various scapes and between them. Today we witness interlinked geographies of these scapes across the globe, making the world’s cities ever more interconnected. Hence, from the mid-1990s onwards, scientists, policy makers and mayors around the world increasingly started to think of our cities as part of networks of global cities, immersed in a space of flows, facilitating a worldwide creative class. However, as has become clear, these global cities did not only produce economic growth and innovations—from tech to finance—but also huge inequalities, both between and within cities, both economically and in terms of cultural and political equity.

To address the tensions and inequalities that have arisen from the emergence of global cities, new approaches are needed that combine top-down urban policy with bottom-up ‘citymaking’ and centre around public values. Such an approach should not so much deny the interconnectedness of cities, the rise of digital networks, or the dynamic interaction between the various scapes. Rather, these should be embraced from a different perspective: a perspective that foregrounds civic relations and public values. In the past decade or so, digital and responsive placemaking has emerged as an approach that does exactly that. Digital and responsive placemakers understand our cities as ‘hybrid spaces’, simultaneously produced by their physical design as well as through their manifestations in virtual networks. The experience of a city is not just that of its buildings and monuments, its materialised institutions like city halls and local libraries and locally embedded cultural practices from weekly markets to critical mass bike rides. Increasingly, the ways in which the city is made up also include mediated versions of these experiences, through urban sensor data, social network practices and the search algorithms of digital map services, all reinforcing each other.

Responsive placemaking integrates this perspective with former ideas about placemaking that go back to Jane Jacobs and William W. Whyte and their groundbreaking visions and methodologies in the field of urban planning and architecture of the 1960s and 1970s. Revolutionary for their time, they brought out the importance of the seemingly trivial practices and rituals of everyday life for the success of cities, focussing on the street as a site in which social relations, trust and urban society could take shape. “The street is the river of life of the city, the place where we come together, the pathway to the center.”2

Responsive placemaking enhances such a perspective with new modes of representing and experiencing the city and the built environment and, more generally, time and space.

Picture above: Public Face I @Mood Gasometer, Berlin Schoeneberg, comissioned by Public Art Lab for the Media Facades Festival, Copyright by Julius von Bismarck and Public Art Lab

New Practices

Responsive placemaking can take various forms, and we’d like to highlight three of these here as examples of projects in which we have been involved ourselves.First, through projects of representation, responsive placemaking highlights the connections between people and places, and contributes to the construction of local publics. They can aid bringing out a ‘sense of place’ as well as a layered, variegated ‘sense of us’.

Second, as collaborative management and governance, responsive placemaking aims at providing these local publics with tools to organise themselves as collectives, addressing civic engagement and social inclusion. It seeks to set up alliances and coalitions of citizens, government representatives and professionals to organise around issues of communal concern, and the collaborative and inclusive management of local resources, from reusable energy communities to commons-based housing cooperatives.

And third, illustrating practices of translocal exchange and mutual learning, responsive placemaking does not approach local initiatives as isolated communities, set in their own time and place. Through the various scapes they are often part of various translocal movements and communities that enable mutual learning.

New Relevance of Translocal Communities and Mutual Learning

As such, in times of global pandemic, responsive placemaking becomes relevant in the context of border closures, spatial isolation, loss of mobility within and between cities, social distancing and quarantine measures. Although the pandemic has had devastating effects for individuals and societies globally, it is also an opportunity to rethink the ways we engage in intercultural dialogue and responsive placemaking in sustainable and equitable formats. As stated by Michele Acuto, director of Connected Cities Lab and professor of global urban politics in the School of Design at the University of Melbourne, “empowerment and community-building need to be at the heart of the digital lessons we are learning from COVID-19.“3 Although we are not travelling, we must work to understand better new types of transnational mobility. According to Federico Parolotto, in post-pandemic landscapes, hyper-mobility may be less feasible and therefore “digital connectivity will emerge as the most prominent transport technologies.”4 Although we are social beings, and most of us crave physical connectedness with others, the pandemic has revealed that we can and must continue to develop effective, inclusive and meaningful ways to connect digitally—novel forms of mobility.

Public Face: How does Berlin feel today?

Public Face5 is a showcase of responsive placemaking contributing to the representation of publics. It transformed a gigantic screen at the Gasometer in Berlin Schoeneberg into a ‘Mood Gasometer’ representing the emotions of the citizens in Berlin. It was developed for the Media Facades Festival6 in 2010 as a realtime data visualisation. The artist team Julius von Bismarck, Benjamin Maus and Richard Wilhelmer recorded and filtered the faces of the citizens with the newly developed software of facial recognition and transmitted the data of the dominating emotions of the group in the form of a emoji in real time on the big screen of the Gasometer with the question, „How does Berlin feel today?” By gathering data in public space, and by scraping social networks, these installations display collective ambiences and moods, communal spatial use patterns, and shared concerns back into public space through media installations. At the same time, and more critically, Public Face also establishes a critical public around the issue of urban surveillance.

Circulate